Activism and Capital-A Architecture Are Alive at the AIA

by Tony P. Wrenn, Hon. AIA

In the 1970s and ’80s, the 120-year debate continued

over who architects are and what they and their professional

association should do. Among the answers that emerged: enhance the

knowledge and talent base to create architecture of the highest

quality, recognize architectural achievement past and present, and

hold it up for the edification of the profession and public

alike.

In the middle of the 1970s, as architects debated whether their

discussions of the profession were self-serving or of benefit to

society, AIA President John M. McGinty, FAIA, noted:

“There is another distinguishing hallmark of

professionalism—the scale upon which the judgments must be

made. And that is a primary allegiance to the discipline imposed by

the prior body of knowledge which circumscribes the profession.

This means a lawyer acts on knowledge of the law; it means a doctor

renders judgments for the good of his patient based on medical

science; and it means an architect places the welfare of his

society and his client ahead of his own when called upon to do so

by the discipline of the art and science of architecture …

That is a lot of baggage we’re carrying on our shoulders. It

implies not only honesty, but selflessness and even more

terrifying, competence.”

In a search for competence, the AIA reorganized its professional

interest committees in the 1970s—which till then were filled

by appointment only—and broadened them to allow all AIA

members, students, and libraries access to their publications,

conferences, and discussions. The Intern-Architect Development

Program (IDP) began, after a period of testing with some 60 firms

in three states proved the program’s value in providing

professional advice, guidance in important areas of knowledge and

skill, and development of a measurement system and educational

materials. Simultaneously, the Institute began developing a

Continuing Education Network.

As orders for AIA documents, widely used throughout the

construction industry, topped more than a million in 1977, updating

of documents continued, along with a complete revision of Chapter

13 of The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice on

General Conditions of the Contract for Construction and a

number of other documents. Distribution by components was

authorized, and 28 signed on to begin distribution at mid-year

1978.

New ways of working and thinking

Technological changes continued, as, as illustrated in the

San Diego 1977 Convention proceedings: “keynote speakers

preached from an elevated ‘cherry picker,’ 20 feet below

convention-goers were entertained and informed by futuristic

‘television walls,’ computerized video displays,

mini-theaters, color-coded exhibits, and an electronic message

signboard reporting daily convention events.”

In Washington, there was still unfinished business, as Congress

seemed bent on extending the West Front of the U.S. Capitol.

“Skillful AIA lobbying and expert advice convinced Congress to

delay funding ... pending further study.” The AIA received

national attention in newspapers and magazines across the country

for its efforts to insure retention of the West Front, avoiding its

destruction and coverup by new work, such as had occurred on the

East Front. Ultimately, the AIA won half its battle, for though the

East Front was extended and covered, the West Front and the Capitol

terraces have been restored. The Mall view of the building still

evidences the quality work of Bulfinch, Latrobe, and Walter.

Nationally,

seven Regional/Urban Design Assistance Teams dispatched during the

year to different communities worried about urban decline.

Preservation, as with the Capitol’s West Front, was

increasingly seen as an option to the widespread demolition that

urban-renewal programs had spawned. “Recycled buildings,”

McGinty said, “can possess a warmth, a scale, a touch of

humanity that is difficult to achieve in new structures. Rebuilt

inner cities can provide convenience, maturity, and relationship to

neighbors and people, and a variety of users that is seldom found

in new suburbs.”

Nationally,

seven Regional/Urban Design Assistance Teams dispatched during the

year to different communities worried about urban decline.

Preservation, as with the Capitol’s West Front, was

increasingly seen as an option to the widespread demolition that

urban-renewal programs had spawned. “Recycled buildings,”

McGinty said, “can possess a warmth, a scale, a touch of

humanity that is difficult to achieve in new structures. Rebuilt

inner cities can provide convenience, maturity, and relationship to

neighbors and people, and a variety of users that is seldom found

in new suburbs.”

Presidents of the New Zealand, Canada, Australia, and British

architectural societies addressed the AIA 1978 Convention,

suggesting an international approach to solving the problems and

promise of architectural practice. That same year, Louis de Moll, a

Fellow of the Institute, was elected president of the International

Union of Architects (UIA), the first American to head the worldwide

organization, established in 1948 and representing some 300,000

architects around the world.

Elevating architects nationally

Still, as architects discussed intangibles, many worried

about their own financial security. AIA President Elmer Botsai,

FAIA, noted: “I know there are some architects who see

profitability as the big goal—and I feel sorry for them. They

should have become dentists.” He suggested concentrating on

education and design rather than the dollar, nonetheless advising

that entry-level architects be paid decent salaries. He noted

“it is shocking that the best way for an architectural student

to increase his future salary is to flunk design and switch to

engineering.” Botsai suggested elevating the AIA Honor Awards

program to presentation at an “elegant black-tie dinner”

and pushing publicity as a means of emphasizing design.

The AIA found other ways to publicize architects nationally,

including cooperation programs with the U.S. Postal Service, which

introduced four stamps, titled “Architecture USA,” with

first-day ceremonies at a special modular post office set up at the

1979 AIA convention in Kansas City. Featuring four historic

buildings, the stamps underscored not just good design but

preservation of that design. The stamp program continued over the

next three years, with a different four buildings each year,

culminating in 1982, the AIA 125th anniversary, with four buildings

by AIA Gold Medalists: Fallingwater, the Illinois Institute of

Technology, the Gropius House, and Dulles International

Airport.

In Washington,

D.C., the AIA financed banners proclaiming “Buildings

Reborn” to be flown on 40 successfully recycled District

buildings. At the same time an exhibit titled “Buildings

Reborn: New Uses, Old Places,” at the Smithsonian’s

Renwick Gallery featured a sampling of the buildings. A brochure

with map pinpointing the buildings urged walkers to have a

look.

In Washington,

D.C., the AIA financed banners proclaiming “Buildings

Reborn” to be flown on 40 successfully recycled District

buildings. At the same time an exhibit titled “Buildings

Reborn: New Uses, Old Places,” at the Smithsonian’s

Renwick Gallery featured a sampling of the buildings. A brochure

with map pinpointing the buildings urged walkers to have a

look.

As energy conservation studies continued, the AIA completed

retrofitting of its headquarters building in early 1978 and

reported in mid-July that the work had already indicated a reduced

energy consumption of 42 percent. At that rate, the cost of the

work would be returned in energy savings in just 2.5 years.

Recognizing the contributions of others

In 1980, the AIA honored Lady Bird Johnson with an AIA

Medal and honorary membership in the Institute for “her role

in both fostering and influencing the architectural profession . .

. In particular, the jury feels that the former First Lady has been

greatly influential in the development of a sound and successful

public attitude toward the conservation and rehabilitation of the

historical architectural resources of this country.” The jury

noted her founding, in 1965, of the Committee for a More Beautiful

Capital—which had, it noted, transformed “Washington,

D.C., into a city of flowers, improved parks, and public

playgrounds.”

The importance

of art in architectural design was also discussed in 1980. The

Board supported including a “significant percent” of a

total architectural project budget to include art as an integral

part of the project and its surroundings. In other action, the

Board voted to support the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and

encouraged AIA components in unratified states to lend support to

pro-ERA activities. It also voted support for “the creation of

a national clearinghouse for architectural and archival

material,” along with the “development of regional

depositories to collect, conserve, and catalog original

architectural documents.”

The importance

of art in architectural design was also discussed in 1980. The

Board supported including a “significant percent” of a

total architectural project budget to include art as an integral

part of the project and its surroundings. In other action, the

Board voted to support the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and

encouraged AIA components in unratified states to lend support to

pro-ERA activities. It also voted support for “the creation of

a national clearinghouse for architectural and archival

material,” along with the “development of regional

depositories to collect, conserve, and catalog original

architectural documents.”

Visions for the profession

In the mid-May 1980 issue of the AIA Journal, the editors

asked a number of architects, educators, and critics

“What’s Next?” The answers are still worth reading.

Among them:

“Largely leaderless in the areas of land use and land

planning, the nation should be turning to the architectural

profession for far-sighted directives and technical guidance. As I

see it, there are no options. Either we, as architects, take our

place on the front line or the velocity of destructive trends will

be totally uncontrollable—and that’s when we will find

ourselves ‘on the edge of survival.’”—Nathaniel

Owings

“Architecture by itself cannot change the world. But it is

part of the world, and it is an enduring way in which change is

expressed.”—Thomas Hines

“I’d

like to see an architecture that makes sense, and does so

gracefully.”—Sarah P. Harkness, FAIA

“I’d

like to see an architecture that makes sense, and does so

gracefully.”—Sarah P. Harkness, FAIA

“Those architects who will write the legislation, design

zoning ordinances, conduct design reviews and act as client for

major institutions and agencies will have a profound

effect.”—Marvin E. Goody

“If architecture does [provide] solutions to the

interconnected esthetic, technological, social and economic

problems of the built environment … behavioral scientists,

computer managers, engineers and interior decorators [will] take

over.”—James Stewart Polshek, FAIA

“[A]rchitecture is our most . . . public. . . art form. . .

[and will] be accorded that status. . . when it is seen as an

essential part of general education.”—Marvin Filler

“The forces whose gravity are not yet fully recognized by

society or its architects are: the scarcity of nonrenewable

resources in general and energy consumption in particular;

worldwide inflation; the widening chasm between the haves and

have-nots. . . [P]rinciples used in past vernacular architecture

that respond directly to the needs of daily life and the

limitations of modest technology will re-emerge.”—Robert

B. Marquis

Direction

’80s at 125

Direction

’80s at 125

AIA President Robert Lawrence, FAIA, would echo Marquis’

sentiments in 1982 when he told conventioneers “We don’t

want an Institute that appeals to the lowest common denominator. We

do not want to reflect a mean, a norm, an average ... The Institute

should be in the forefront of efforts to raise public awareness of

quality in our environment.”

The Direction ’80s Task Force had begun work in 1981 on a

report that would prioritize goals in five areas—body of

knowledge, education, public policy, communications, and

organization—and define appropriate roles for national, state,

and local components of the AIA. Concepts gleaned nationwide set

the agenda for a 1982 goals conference in Washington, D.C.

Delegates included representatives from all AIA regions,

government, education, and industry, along with non-architects. The

report focused internally on architects and externally on

architecture.

1982 marked the 125th anniversary of the AIA, celebrated with an

exhibit at the Octagon that recreated an architect’s office as

it might have appeared in 1857 contrasted with the actual operating

office of a Washington architect, where the drafting table was

replaced by CAD. In the AIA building, an exhibit of materials from

the AIA Archives featured items that reflected “For the

Record” the 125-year evolution of architecture from the

practice of a few to a profession. A week-long birthday party in

April featured not just the exhibits but concerts, forums, and

tours and culminated in a gala reception for invited guests,

including ambassadors, government officials, AIA officers, members,

and staff. Birthday activities brought thousands into the

courtyard, Octagon, and AIA building for an introduction to the

AIA.

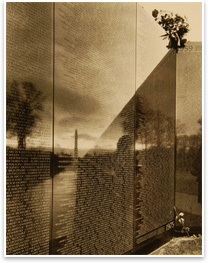

The Vietnam

Memorial

The Vietnam

Memorial

One series of events of the long hot summer of 1982 had

begun earlier when representatives of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Fund came to the AIA seeking guidelines for an architectural

competition. From 1,420 entries, the jury, with Paul Spreiregan as

competition adviser, selected Maya Lin, 22, a recent Yale

University architecture graduate. Some argued the

design—Modern, abstract, black, and below ground, with the

names of U.S. troops who died in Vietnam—was anti-war;

different from other Washington memorials. Veterans groups, with

the support of several nationally known figures, including

Secretary of the Interior James Watt, asked for a flagpole behind

the apex of the monument and a statue of three soldiers at the

intersection of the monument walls.

Lin steadfastly supported her design, and the AIA lent its support

“to protect the public interest and preserve design excellence

in the federal city.” In testimony before the U.S. Commission

of Fine Arts, AIA President Lawrence contrasted the “Open,

careful professional design competition process,” that chose

Lin’s design, with the “closed, politicized,

nonprofessional” process that led to the proposed

design.

“It is a new scheme in which the statue becomes the actual

memorial and the wall designed by Lin an almost incidental backdrop

supporting a flagpole,” stated the AIA position. “The

statue would be a tortured and ambiguous memorial seemingly anxious

to make a statement about the war but uncertain what the statement

should be. This is precisely the kind of thing that the competition

program sought to avoid and what the winning design, in quiet power

and dignity, totally avoided … The best design was selected.

That is the design that should come to fruition. Our veterans

deserve nothing less, and the public trust demands nothing

more.” The AIA campaigned throughout the long summer and fall

for Lin’s design, just as it had in the first quarter of the

20th century for Henry Bacon’s design for the Lincoln Memorial

less than 150 yards away.

Ultimately the

Commission of Fine Arts noted that the Lin design articulated no

entry point and proposed that the flag and sculpture be part of an

entrance removed from the original design, which the AIA supported

“so that this country’s memorial to those who served in

Vietnam can be dedicated this November 11 as originally

scheduled.”

Ultimately the

Commission of Fine Arts noted that the Lin design articulated no

entry point and proposed that the flag and sculpture be part of an

entrance removed from the original design, which the AIA supported

“so that this country’s memorial to those who served in

Vietnam can be dedicated this November 11 as originally

scheduled.”

The Memorial was dedicated and has become the most visited site in

Washington. Lin’s design is breathtaking in its beauty and

emotional impact. Still, notes Raymond Rhinehart, Hon. AIA, who was

engaged in the AIA’s fight for Lin’s design, “the

controversy ... simmers on; new figures are added to the sculpture

group, the now-approved underground visitor center ... It

won’t end probably even after the last veteran dies. The hurt

is that profound, and the scar that deep. But the memorial also

endures.”

Celebrating the old and ringing in the new

In 1983, the Institute, the Library of Congress, and the National

Park Service celebrated the 50th Anniversary of the Historic

American Buildings Survey (HABS). Operated under a tripartite

agreement, HABS started as a Depression-era program to provide work

to unemployed architects and drafters. In its 50 years, the Survey

had recorded more than 16,000 structures and sites. “Since

1933, HABS has documented structures from all 50 states, the

District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

Currently, more than 40,000 measured drawings, 77,000 photographs

and 42,000 pages of written architectural and historical data are

housed in the Library of Congress and are available for public

use.” HABS continues as an active program.

Concurrently,

a new publication, Architectural Technology magazine saw

the light of day. The new quarterly for AIA members was intended to

respond “to the need of the profession to have the best that

is being thought and written today about the science and practice

of architecture.”

Concurrently,

a new publication, Architectural Technology magazine saw

the light of day. The new quarterly for AIA members was intended to

respond “to the need of the profession to have the best that

is being thought and written today about the science and practice

of architecture.”

The same year, the AIA Journal changed its name to

Architecture. “The new name reflects the fact that

the magazine speaks for the profession, not AIA per se, and that

reporting on AIA activities, while part of its content, is by no

means the major part,” said editor Donald Canty.

It was a year of restructuring within the Institute, as well. A

Governance Task Force began “to identify the authority and

responsibility of all bodies within the Institute, including the

Board of Directors, the Executive Committee, commissions, regional

and state organizations, chapters, and national committees to study

the Institute’s responsiveness to the membership ... and to

develop a strategy for allocation ... [of] Institute resources to

encourage ... effective communication with and participation of the

membership.” The topic was, and remains, an ongoing

process.

A new dawning for architecture

With his architectural critique, A Vision of

Britain, still four years from the making, Prince Charles came

to the AIA in 1985 to hear about and discuss successful American

approaches to urban revitalization. Representatives from several

American cities with successful design control programs that had

led to urban revitalization appeared and participated. “While

no one in this room professes to have the definitive formula for

successful urban revitalization, each of us has been involved in

successful urban revitalization processes. It’s our experience

as participants in these efforts that we have to share. Perhaps

some of the elements of the process are transferable and will be of

benefit to other cities or countries,” said David N. Lewis,

AIA, RIBA, of Philadelphia. Prince Charles expressed the hope that

RIBA and the AIA would work together in studying and solving urban

problems.

At one convention session in 1985, three panel members discussed

the nature “of the architect’s contribution to the design

process.” Hugh Newell Jacobsen, FAIA, Washington, D.C., stated

that “there is a world of difference between a building and a

work of architecture ... We’re building less and less of

architecture and losing more and more to the lawyers and bankers,

who don’t know their ass from page 12. . . We are responsible

for the mess out there, not the developers. Our basic role is to

educate our clients. Our own sloth is the enemy. We were better

architects 50 years ago, because we had higher principles. . . We

don’t supervise or inspect work. We observe

it—periodically. That troubles me.” Jacobsen admitted

that saying no to an inflexible program or a difficult client was

not easy but stated flatly that “building a turkey is

worse.”

Architectural Technology was folded into

Architecture in October of 1986 to become “the most

complete magazine in the field.” Membership in the decade

1977-1986 grew from 24,000 to just under 50,000. Dues income,

“a total aggregate of basic and supplemental dues,”

received went from $4 million to more than $9 million. And the

annual budget for Institute operation rose from $8 million to $26

million.

Brendan Gill, keynote speaker at the 1986 AIA Convention noted this

growth and urged architects to take advantage of the increasing

interest in architecture. “Until recently, the profession of

architecture was not one to be entered to become rich, much less

famous. It is only within the last decade that architecture has

become fashionable . . . One is expected at dinner parties to speak

easily of contemporary icons such as Venturi and Gwathmey and Meier

and Jahn. . . Now architecture—or rather architects—are

all the rage.”

AIA President John A. Busby Jr., FAIA, followed Gill in suggesting

architects take advantage of their opportunities, ending by saying

“We proceed, we persist, we create, we change in order to give

the world beauty, shelter, home and sanctuary. The new age is

dawning, and this profession will build it. It is the greatest

challenge that we face. And with skill, commitment, and willingness

to adapt to new realities, it is going to be our greatest

triumph.”

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page