A new century beckons

by Tony Wrenn, Hon. AIA

AIA President Leon Chatelain Jr., a Washingtonian, presided over

the AIA during its Centennial Year in 1957, with a clear message to

the membership: “All that the architects of America have come

to know in the hundred years since 1857, all of the ingredients and

technology and craft that is architecture in 1957, can barely

answer the need of our times. Of the future we know only this: that

its pressures and the sum of the daily hungers of its people will

pull us into a frenzy of coordinated creativity. The hundred years

that have crowded in behind us have pushed us into another century

of professional evolution. We have neither time nor balance to

stand still, to contemplate our past. In the year of our

centennial, let us look with care where we are going—into the

future. We are needed there.”

The centennial

celebration began in New York City, the AIA’s birthplace, with

unveiling of a plaque at 111 Broadway, the site of the first AIA

meeting. Simultaneously, the U.S. Postal officials issued a

commemorative stamp marking the centennial. Featuring a classical

column with a superimposed Wrightian column, it cost just 3 cents

and was heavily used by the Institute and members.

The centennial

celebration began in New York City, the AIA’s birthplace, with

unveiling of a plaque at 111 Broadway, the site of the first AIA

meeting. Simultaneously, the U.S. Postal officials issued a

commemorative stamp marking the centennial. Featuring a classical

column with a superimposed Wrightian column, it cost just 3 cents

and was heavily used by the Institute and members.

The centennial convention, held May 13–17 in Washington, D.C.,

played like a great pipe organ with all stops out. Agnes E. Meyer,

David Finley, Paul Tillich, Bennett Cerf, Howard Mitchell, Leo

Friedlander, Henry F. Luce, Walter P. Reuther, and Lilian Gish were

speakers and participants. Gish argued for architects signing their

buildings, and blamed the architects for the public’s lack of

knowledge of what architects produced. “You remind me of my

own family, who believe a lady should have her name in the public

print just three times—when she is born, when she is married

and when she dies. In my lifetime I have heard of only two

architects: Frank Lloyd Wright, God bless him for what he has done

to make even the word ‘Architecture’ known to us; and the

other is a memory of my childhood, Stanford White who got shot.

(Laughter) A prize fighter gets more publicity and in some

instances a truck driver is better paid. It would seem that our

system of values has reached an Alice in Wonderland absurdity,

worthy only of satire.”

Sculptor

Sidney Waugh designed a bronze Centennial Medal, for convention

attendees. One medal was cast in Gold and presented to President

Eisenhower, who “was very gracious and received this in his

private chambers after which he appeared before the

reporters.” Film of the presentation was shown at the

convention and a message from Eisenhower was read: “From the

earliest days of our Republic the profession of architecture has

contributed to the growing industry of our land, to the development

of our public buildings and to raising in form and fabric the

aspirations of our people.”

Sculptor

Sidney Waugh designed a bronze Centennial Medal, for convention

attendees. One medal was cast in Gold and presented to President

Eisenhower, who “was very gracious and received this in his

private chambers after which he appeared before the

reporters.” Film of the presentation was shown at the

convention and a message from Eisenhower was read: “From the

earliest days of our Republic the profession of architecture has

contributed to the growing industry of our land, to the development

of our public buildings and to raising in form and fabric the

aspirations of our people.”

Recording the past—in 90 days

Henry H. Saylor, Fellow of the Institute and longtime

editor of its Journal “recognized the anomaly of

celebrating a history that had never been recorded. Although the

emphasis of the celebration was rightly put on the future rather

than the past—a new century beckons—it seemed advisable

to make at least a gesture toward the road over which we have

traveled,” and Saylor did something which perhaps no other

member could have done.

“With but ninety days available for the reading of one hundred

years of proceedings, minutes, documents, and doing the supporting

research, the writing of a definitive history of the

Institute’s first hundred years was out of the

question....This hasty sketch is the alternative....Perhaps,

however, with a frank admission of its shortcomings, this little

volume will give an occasional glimpse, as through a glass darkly,

of the way The Institute has come to a maturity which enables us to

look with confidence to the century that beckons,” Saylor

wrote. He penned that preface in March, and his The

A.I.A.’s First Hundred Years, was published as the May

issue of the AIA Journal, ready to be rebound as a book

for all who desired. It has served the Institute well, with its

topical presentation, a time line and a useful index.

Celebratory activities abound

The National Gallery of Arts’ “One Hundred Years

of Architecture in America” exhibition and accompanying

catalog prepared by Fritz Gutheim featured, in addition to

buildings from the Institute’s century, a listing of 10

contemporary buildings that would influence America’s future.

The organizers were not above doctoring photographs to make a

point. The Connecticut Life Insurance Company Building appeared in

a dramatic photograph across a snowy field with a fence in the

foreground. It had everything but scale, which they provided by

placing a cutout of a hunter with rifle in the foreground

The AIA awarded two Gold Medals during the Centennial celebration.

One went to Louis Skidmore with a citation that noted that previous

medals had been given largely upon individual service, while

“you have built an organization with the name of Skidmore,

Owings & Merrill.” The other Gold Medal, labeled the

“Centennial Gold Medal of Honor,” was given to Ralph

Walker, essentially for service to the profession, a reason for

recognition as different as was that of Skidmore. Walker would not

disappoint, even in his acceptance. He insisted that America’s

cities and her environment were the AIA’s responsibility and

must be protected and preserved. Indeed, if one follows the trail

of words before Institute boards, committees, and chapters that

Walker left us, it is clear that for years he had been the

AIA’s guide and conscience.

A capital win, a Capitol loss

One action in the AIA’s centennial year seemed out of

place: the Institute’s Douglas Orr, former AIA president and

member of the President’s Advisory Commission on Presidential

Office Space, argued in an article on “New Offices for the

White House,” which appeared in the December 1957

Journal, for the advantages of replacing the Alfred B.

Mullett’s 1888 State, War and Navy Building (the former OEOB,

or Old Executive Office Building, today known as the Eisenhower

Building) and noted that “because the White House has been one

of the prime concerns of the Institute, whatever develops in

providing the President with adequate quarters is of great

import.”

A giant French Second Empire pile, the building may have had few

vocal friends, but that would change quickly. It has been said that

President Eisenhower’s horror at the cost of demolishing the

vast stone and iron building actually saved it, but assessments of

the building’s architectural value also played a part. The

Journal carried in its May 1959 issue, an article titled

“Architecture Worth Saving,” which included, with

illustration, the State, War and Navy Building. It today serves the

purpose Orr and his committee envisioned for the site, but through

retrofitting, not through demolition and new construction.

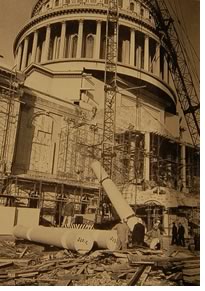

Across the

city, the extension of the East Front of the Capitol loomed close

to becoming a reality in 1958, as the Congress refused to budge.

The AIA Board asked the convention to reaffirm its opposition.

Ralph Walker again emerged as a powerful spokesperson, writing

about it in the January and June 1958 Journals and

speaking at convention. Although AIA members were involved in the

proposed work to extend the East Front, Walker believed “there

are times when the Institute has to take the position, in regard to

the public welfare, that it is bigger than any of its members;

otherwise, it, The Institute, will degenerate into a trade

association having no other ambition than that of merely obtaining

jobs for its members.” Marcellus Wright labeled the extension

a “disastrous move to toy with the East Front of our National

Capitol.”

Across the

city, the extension of the East Front of the Capitol loomed close

to becoming a reality in 1958, as the Congress refused to budge.

The AIA Board asked the convention to reaffirm its opposition.

Ralph Walker again emerged as a powerful spokesperson, writing

about it in the January and June 1958 Journals and

speaking at convention. Although AIA members were involved in the

proposed work to extend the East Front, Walker believed “there

are times when the Institute has to take the position, in regard to

the public welfare, that it is bigger than any of its members;

otherwise, it, The Institute, will degenerate into a trade

association having no other ambition than that of merely obtaining

jobs for its members.” Marcellus Wright labeled the extension

a “disastrous move to toy with the East Front of our National

Capitol.”

The Convention resolution, publicized widely and made known to the

members of Congress, did not carry the necessary weight, and work

on the “much debated project commenced. The new front is

scheduled for completion in time for the 1960 inauguration.”

The Journal reported in its April 1959 issue that the

“columns from the portico lay wearily on the ground...Sad

sight.”

Fighting “urban removal”

The 1961 Board noted the growing importance of The

Octagon, the AIA’ s “Embassy in Washington,” where

visitors from around the world came to see and talk about

architecture, and applauded President John Fitzgerald

Kennedy’s new view of Lafayette Square across Pennsylvania

Avenue from the White House. The AIA Committee on the National

Capital was involved and “after reviewing proposals for the

development...the committee issued a statement expressing its

confidence ‘that through skillful design,' Lafayette Square

can become an area of great architectural importance to future

generations...The committee believes it is quite possible to

restore the integrity of the square from its present cluttered

appearance. Carefully designed new buildings framing the park can

complement the White House rather than overwhelm it if kept in

proper scale.”

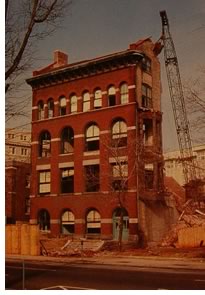

Prior plans had called for demolition of everything on the Jackson

Place side of the Square, except Blair House, the President’s

Guest House, and Decatur House, a property of the National Trust

for Historic Preservation. On the Madison Place side, nothing would

be saved. The new plan called for the retention of historic

buildings on both sides of the square, new buildings of like scale

as fill around the Park’s perimeter, and the construction of

tall buildings in the center of the blocks.

That plan would change architecture in the inner city. Facades

would be saved (even when whole buildings could not be), and infill

buildings would be compatible in scale and materials with the

existing historic material. Contemporary buildings in historic

settings became the norm. The positive effects of this—in

preservation, beauty, urban scale, and development costs—were

substantial. Simultaneous planning of the AIA’s new

headquarters buttressed the Lafayette Square plan; even as the

Institute reorganized its staff and goals, it planned for “a

new headquarters to serve as a national center for the advancement

of the environment arts and sciences.”

Growing

interest in urbanism

Growing

interest in urbanism

President Kennedy sent greetings to the 1961 convention,

recognizing that ”your role and work in urban renewal is a

major one, and I am glad to send you personal greetings for your

convention and its timely theme of redesigning urban America. Your

current influence and work can reshape the urban life of this

country, and is a challenge that no other generation of architects

has yet had. I deeply appreciate your support on the Housing Bill

and the Department of Urban Affairs legislation.”

Discussion of the new AIA headquarters building, “adequate to

the growing needs of the Institute and worthy of the importance and

dignity of the architectural profession,” continued in 1962.

Still, its larger setting was of concern as the AIA Board and its

Committee on the National Capitol deplored “ the way the

visual appearance of streets and avenues is being spoiled by

cutting down of trees, narrowing of sidewalks, etc., and on such

places as the Mall and other park areas by the thousands of parked

cars. It notes that this generation has a responsibility to

preserve the parks, malls and open spaces that are our heritage and

they must not be frittered away to accommodate traffic or

commercial uses.”

The concern included support of the “Fine Arts Commission...in

urging that further construction on the proposed inner loop be

stopped, believing that a comprehensive and effective mass transit

program, now under study, may well eliminate the need for big

highways into and around the downtown area.” It was too late

in some cases, and major highways passed beneath the Mall and

surfaced within sight of the Capitol’s west front, and crossed

the Potomac over Theodore Roosevelt Island, in sight of the Lincoln

Memorial, chiseling away at the relationship of Edward Durrell

Stone’s National Cultural Center [now the Kennedy Center] to

the city. Interstate 66 was finally interrupted there however, and

its open gash across the Mall in front of the Lincoln Memorial

never materialized.

Honoring

Kennedy

Honoring

Kennedy

The 1963 Board “cited with honor John Fitzgerald

Kennedy, President of the United States, in a unanimous resolution,

which comes within no established award and is given for the first

time.” When AIA President J. Roy Carroll Jr. presented Kennedy

with the award at the White House on May 22, he said, “But

you, sir, are the first President of the United States—except

possibly the first and third ones—who has had a vision of what

architecture and its allied arts can mean to the people of the

nation, and of what the careful nurturing of the architecture of

the city of Washington can mean to those millions who come here to

pay homage to the heart of their country.”

In the same year, AIA President Henry L. Wright lauded the AIA for

its difference from other professional and trade associations.

“It is actually operated under the direction of the

members....The forty-five committees, and 350 architects, members

who serve on them, are working committees.” He took

note of the aging population and its increased leisure time.

“Our plans for the future must consider the leisure

time of tomorrow’s citizen. If our urban design encompasses

thoughts for recreation facilities, for increased learning of all

things, at all ages, and if our plans include facilities for the

development and expression of the arts as well as the sciences, our

civilization may experience a renaissance of culture beyond our

most fervent hopes.”

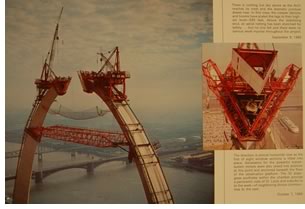

Meeting in St.

Louis in 1964, members watched and marveled at the construction of

Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch. It served as the symbol for that

year’s convention and its theme: “The City—Visible

and Invisible.”

Meeting in St.

Louis in 1964, members watched and marveled at the construction of

Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch. It served as the symbol for that

year’s convention and its theme: “The City—Visible

and Invisible.”

Toward a new headquarters

Work toward construction of the new National Headquarters Building

behind the Octagon began with a competition brochure issued on

January 22, 1964 that established the rules, not just for the AIA

building, but, it could be argued, for future contemporary

buildings in historic settings. “The object of the competition

is the creation of a design for a new National Headquarters

Building that will satisfy both physical and spiritual

functions—a building of special architectural significance,

establishing a symbol of the creative genius of our time yet

complimenting, protecting and preserving a cherished symbol of

another time, the historic Octagon House,” it said. In

suggesting the “Character of Building” the announcement

was specific: “The character of the new building must not only

be compatible with the Octagon, it must preserve, compliment and

enhance the historic residence. However, this should not be

interpreted as suggesting the copying of the form or detailing of

William Thornton’s design, nor any stylistic re-creation of

colonial architecture. What is wanted is a more thoughtful, more

sensitive and more meaningful solution; an exciting demonstration

that fresh and contemporary architecture can live in harmony with

fine architecture of another period; each statement giving the

other more meaning and contributing to the delight of the entire

building complex.”

Registration

for the competition ended on March 15, 1964 with 625 registrants,

221 of whom actually submitted entries. Seven first stage winners,

selected on May 18, were asked to prepare final drawings. The final

stage ended on October 1, and on November 2 the competition winner,

the firm of Mitchell/Giurgola, was announced. “The winning

design envisages a five-story, red-brick structure featuring a

semi-circular glazed wall which will embrace the gardens and

Octagon House. It will enclose about 50,000 square feet of usable

floor space and its estimated cost is $1,450,000. An additional

$30,000 has been allocated for sculpture or other fine

arts....tentative plans indicate working drawings should be

completed by March 1966. The Octagon House, which will be closed

during the construction period, will also undergo some

renovation.”

Registration

for the competition ended on March 15, 1964 with 625 registrants,

221 of whom actually submitted entries. Seven first stage winners,

selected on May 18, were asked to prepare final drawings. The final

stage ended on October 1, and on November 2 the competition winner,

the firm of Mitchell/Giurgola, was announced. “The winning

design envisages a five-story, red-brick structure featuring a

semi-circular glazed wall which will embrace the gardens and

Octagon House. It will enclose about 50,000 square feet of usable

floor space and its estimated cost is $1,450,000. An additional

$30,000 has been allocated for sculpture or other fine

arts....tentative plans indicate working drawings should be

completed by March 1966. The Octagon House, which will be closed

during the construction period, will also undergo some

renovation.”

The new building was driving the AIA. Institute President Morris

Ketchum told the convention in Denver in late June 1966: “The

total objective will be to create on an enlarged site a new

headquarters building adequate for our growth, a complete

restoration of The Octagon as a beautiful landmark of our

architectural heritage and a garden which states our principles of

open space and contribute to the scale and harmony of the two

buildings. In short, the design of the entire complex must

exemplify what our profession urges our clients to do.”

It would not be an easy task.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page