by Tony P. Wrenn, Hon. AIA

The decade

following World War II did not begin easily for the AIA. Although

it had let the contract for construction of a new Administration

Building in 1940, and construction was completed, the war

intervened, and the Institute did not gain occupancy for another

eight years. The federal government had taken over the two-story

brick building—which wrapped around the rear of the Octagon

garden, stretching from New York Avenue to the Octagon

stable—at an annual rental of $12,000. A fence separated the

Administration Building from the Octagon garden. In the meantime,

the stable along the north part of the property, which the District

government had condemned, was stabilized and the cornice of the new

building wrapped around it. In 1947, the government agreed to

return the building to the AIA in June of 1948.

The decade

following World War II did not begin easily for the AIA. Although

it had let the contract for construction of a new Administration

Building in 1940, and construction was completed, the war

intervened, and the Institute did not gain occupancy for another

eight years. The federal government had taken over the two-story

brick building—which wrapped around the rear of the Octagon

garden, stretching from New York Avenue to the Octagon

stable—at an annual rental of $12,000. A fence separated the

Administration Building from the Octagon garden. In the meantime,

the stable along the north part of the property, which the District

government had condemned, was stabilized and the cornice of the new

building wrapped around it. In 1947, the government agreed to

return the building to the AIA in June of 1948.

The Octagon itself then changed from an office building to a

museum, taking on again its intended “role as a

gentleman’s town house of 1800.” Office functions moved

to the Administration Building, and the two structures were joined

by a garden intended to serve as “a Memorial to Institute men

who made the supreme sacrifice in World Wars I and II.”

Gilmore Clarke, landscape architect and then chair of the U.S.

Commission of Fine Arts would design the garden, and sculptor Lee

Lawrie would create a stele to be erected against the

Octagon’s rear wall. Ultimately, the AIA argued with Gilmore,

who was donating his services, and fired him, forcing an apology

from AIA President Ralph Walker. Lawrie did finish his stele.

Although a handsome work by a major American sculptor, it remains

largely unknown, its setting never completed.

Also in the

spirit of consolidation, in 1947 the Institute brought together all

announcements and bulletins into one publication, aptly named the

Bulletin, and adopted a new AIA lapel pin—Octagon

shaped, with a gold border. “The American Institute of

Architects 1857" appeared on a maroon background, intended to

announce immediately to all that the wearer was an architect.

Also in the

spirit of consolidation, in 1947 the Institute brought together all

announcements and bulletins into one publication, aptly named the

Bulletin, and adopted a new AIA lapel pin—Octagon

shaped, with a gold border. “The American Institute of

Architects 1857" appeared on a maroon background, intended to

announce immediately to all that the wearer was an architect.

“So must architecture be understood”

In 1947, Eliel Saarinen was given the AIA Gold Medal in

ceremonies at the 79th AIA Convention in Grand Rapids, Mich. He

noted in his acceptance speech that “the problem of

architecture is to house man, and that holds true whether we

consider the room, the home, the neighborhood, the town, or the

city. In short, the provision of all the spaces where human life

and work goes on belongs to the realm of architecture. So must

architecture be understood. And because architecture has not been

so understood, is the reason why things have gone

astray.”

It was also in 1947 that the competition for the Jefferson National

Expansion Memorial in St. Louis was announced, a competition won by

Eliel Saarinen’s son, Eero. The resulting Gateway Arch has

become one of the nation’s best known architectural landmarks.

(Eero joined his father as an AIA Gold Medalist in 1962.)

The

Journal of the AIA for July 1947 carried two articles on

what might be labeled the public’s interest in the visual side

of architecture. In measuring such interest, Edwin Bateman Morris,

a Fellow of the Institute, clocked some 1,870 persons as they

passed two Washington buildings. “I do not like to think of an

art without an audience. If I were a playwright, I should not like

to have the seats unoccupied. If a writer of books, I should not

like to have my books unread. If a musician, my music

unheard,” he wrote. As they passed the chosen buildings he

would count how many actually looked at the buildings, using that

as a gauge of their interest in architecture. Only two people

actually stopped and looked. “Active disapproval by the public

we could cope with. But inattention, boredom! It is hard to talk to

them; they are not listening,” he concluded. In another case,

the magazine reported that the builders of an addition to the John

Hancock building in Boston erected a grandstand from which

passersby could stop and watch the “bulldozers, steam shovels

and pile drivers in action.” In 11 months some 135,000 people

actually stopped to take in the show. “Are people,” the

magazine asked, “as deeply interested in architecture as they

are in construction?”

The

Journal of the AIA for July 1947 carried two articles on

what might be labeled the public’s interest in the visual side

of architecture. In measuring such interest, Edwin Bateman Morris,

a Fellow of the Institute, clocked some 1,870 persons as they

passed two Washington buildings. “I do not like to think of an

art without an audience. If I were a playwright, I should not like

to have the seats unoccupied. If a writer of books, I should not

like to have my books unread. If a musician, my music

unheard,” he wrote. As they passed the chosen buildings he

would count how many actually looked at the buildings, using that

as a gauge of their interest in architecture. Only two people

actually stopped and looked. “Active disapproval by the public

we could cope with. But inattention, boredom! It is hard to talk to

them; they are not listening,” he concluded. In another case,

the magazine reported that the builders of an addition to the John

Hancock building in Boston erected a grandstand from which

passersby could stop and watch the “bulldozers, steam shovels

and pile drivers in action.” In 11 months some 135,000 people

actually stopped to take in the show. “Are people,” the

magazine asked, “as deeply interested in architecture as they

are in construction?”

Morris could not give up his quest to determine whether

architecture visually interested the public and sent a

questionnaire to 500 architects asking “What buildings give

you a thrill?” No matter how he rated the results, four

buildings came out on top: The Folger Library, the Lincoln

Memorial, Rockefeller Center, and the Nebraska State Capitol.

Morris, in reporting the results of his survey, noted that a poll

done by the Federal Architect in the 1930s had listed the

Empire State Building first, Lincoln Memorial second, and the

Nebraska State Capitol third.

The AIA continues White House stewardship

In April 1947, President Harry Truman asked the U.S. Commission of

Fine Arts to approve a second level balcony on the South Portico of

the White House, opening a potential fight with the AIA. The

Commission advised against it, but noted that it had no veto power

and requested that if the president were determined to proceed,

“he ask some architect of reputation to advise.” Truman

asked William Adams Delano, a Fellow of the Institute who, in 1927

had, during the Coolidge administration “put a new and higher

roof on the main building to gain needed bedrooms.” Delano was

well known to both the Commission and the AIA and accepted the

challenge. The AIA, which had initially opposed the balcony idea,

later publicly praised the “skill and good taste” with

which the work was accomplished.

The White

House soon became a greater concern when its condition was reported

to be unsafe. In February 1948, President Harry Truman asked a

committee that included AIA President Douglas Orr to investigate

and make recommendations. From the first meeting it was clear that

the White House was suffering from both age and misuse and was a

safety and fire hazard. In September, the Commission concluded that

“The conditions were of so serious a nature that it was

considered necessary to evacuate the building.” Early in 1949,

Congress adopted Public Law No. 40, “The Commission on the

Renovation of the Executive Mansion.” The president was

allowed to appoint two members of the six-member commission, and

one of his appointees was AIA President Orr. President Truman and

his family moved across Pennsylvania Avenue to the president’s

guest quarters, Blair House, and the work began under White House

architect Lorenzo Winslow. “A complete record set of

photographs of the entire building was made, and Mr. Winslow had

prepared an exact record set of drawings of the entire building and

its details.

The White

House soon became a greater concern when its condition was reported

to be unsafe. In February 1948, President Harry Truman asked a

committee that included AIA President Douglas Orr to investigate

and make recommendations. From the first meeting it was clear that

the White House was suffering from both age and misuse and was a

safety and fire hazard. In September, the Commission concluded that

“The conditions were of so serious a nature that it was

considered necessary to evacuate the building.” Early in 1949,

Congress adopted Public Law No. 40, “The Commission on the

Renovation of the Executive Mansion.” The president was

allowed to appoint two members of the six-member commission, and

one of his appointees was AIA President Orr. President Truman and

his family moved across Pennsylvania Avenue to the president’s

guest quarters, Blair House, and the work began under White House

architect Lorenzo Winslow. “A complete record set of

photographs of the entire building was made, and Mr. Winslow had

prepared an exact record set of drawings of the entire building and

its details.

“After a diligent and thorough study of the whole matter, the

Commission announced its decision to retain the outer walls, third

floor and roof and put a new steel frame within the building and

reconstruct the interiors.” President Truman ensured support

of the architects by granting them access to his office and

involving them in the rebuilding process.

Gold Medalist Wright: “A long time coming”

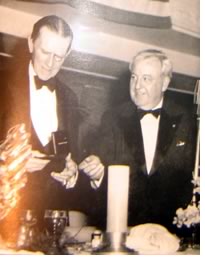

One unforgettable event of 1949 was the awarding of the

AIA Gold Medal to Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright had never become a

member of the AIA and his route to the Gold Medal was not an easy

one. He had received the Royal Institute of British Architects Gold

in 1941 and in accepting the AIA gold commented: “It’s

been a long time coming from home. But here it is at last.

“I have

heard myself referred to as a great architect,” Wright said.

“I have heard myself referred to as the greatest living

architect. I have heard myself referred to as the greatest

architect who ever lived. Now, wouldn’t you think that ought

to move you? Well it doesn’t.” The architect, he said,

“must be a creator. He must perceive beyond the

present. He must see pretty far ahead ... Now, I have been right

about a good many things—that’s the basis of a good deal

of my errors ... Now I want to call your attention to one thing. I

have built it. I have built it. [sic] Therein lies the source of my

errors. Why I can stand here tonight, look you in the face and

insult you—because well, I don’t think many of you

realize what it is that has happened, or is happening in the world

that is now coming toward us.”

“I have

heard myself referred to as a great architect,” Wright said.

“I have heard myself referred to as the greatest living

architect. I have heard myself referred to as the greatest

architect who ever lived. Now, wouldn’t you think that ought

to move you? Well it doesn’t.” The architect, he said,

“must be a creator. He must perceive beyond the

present. He must see pretty far ahead ... Now, I have been right

about a good many things—that’s the basis of a good deal

of my errors ... Now I want to call your attention to one thing. I

have built it. I have built it. [sic] Therein lies the source of my

errors. Why I can stand here tonight, look you in the face and

insult you—because well, I don’t think many of you

realize what it is that has happened, or is happening in the world

that is now coming toward us.”

Later, Journal editor Henry Saylor reported “one of

those moments worthy of being recorded in history.” It

occurred at the AIA President’s reception when J. Ernest

Fender, past-president of the Structural Clay Products Institute

was being guided through the room by one of his staff. “Coming

suddenly upon Frank Lloyd Wright, the guide seized the opportunity

of presenting his past-president to the architect. Whether

premeditated or unthinking, we shall never know, but Mr.

Fender’s words across the handshake were, ‘The name,

please?’”

In an arms race, houses lose

Two wars were going on in the early 1950s. As atom bomb testing

continued and the Cold War between Western nations and the Soviet

bloc got colder, fighting erupted in Korea. Architects talked of

“realistic policies of industrial and government location that

would tend to prevent further overcrowding of target areas,”

and asked Congress to restore cuts made in defense housing, they

urged that something be done about civil defense. They worried, not

just about the actual fighting but about “the long range

implications of A-bombs ... in enemy hands.”

Even as the

architect was being shown sympathetically by Hollywood in “Mr.

Blanding Builds His Dream House,” the Soviets portrayed him in

another guise altogether. In one bit of radio propaganda, Charles

Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewit was “resurrected and pressed

into service for a return visit to the United States.” In the

Radio Moscow broadcast “Chuzzlewit arrives in present day

Manhattan as, of all things, AN ARCHITECT SEEKING WORK.” In

the Soviet propaganda piece “he is laughed to scorn, told that

thousands of American architects are unemployed because the nation

is engaged solely in producing arms, not houses.”

Even as the

architect was being shown sympathetically by Hollywood in “Mr.

Blanding Builds His Dream House,” the Soviets portrayed him in

another guise altogether. In one bit of radio propaganda, Charles

Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewit was “resurrected and pressed

into service for a return visit to the United States.” In the

Radio Moscow broadcast “Chuzzlewit arrives in present day

Manhattan as, of all things, AN ARCHITECT SEEKING WORK.” In

the Soviet propaganda piece “he is laughed to scorn, told that

thousands of American architects are unemployed because the nation

is engaged solely in producing arms, not houses.”

The AIA’s own saw the 1950s with little kindness. AIA

President Ralph Walker noted in his convention speech in Chicago,

May 8, 1951, “Our urban way of living here in America has

resulted to date in an extremely ugly civilization. On my way out

here I stood on a platform of the Harmon Station of the New York

Central Railroad and looked about in a radius roughly of a mile.

Everywhere were the manifestations of the engineer world—not a

building, not a lamp post, not a structure of any kind, including

equipment, that could be seen had been designed by an

architect—the result was an appalling and frightful ugliness

... The architect,” he said, “must be interested in the

social and economic implications of modern life. He must realize

that he is the designer of cities—that the modern ugliness

developed when he lost control—when utility took the place of

beauty ... Even in times of crisis we must do better than replace

the dirt of the slum with the monotony of the housing project; of

replacing the obsolete city with the unplanned sprawl.”

A gift to Chartres

Though the memorial garden at the Octagon had not been brought to

the happiest end, the idea of a memorial in Europe was. The gift to

Chartres of a stained glass window was conceived in 1951, and in

1954 the window was installed. It replaced a window destroyed

during the French Revolution. Its opening, which had been filled,

was reopened to receive the AIA gift. Dedicated to St. Fulbert who

founded Chartres and built the first church there, it was designed

by Francois Lorin whose family had cared for the glass of the

cathedral for three generations, assisted by Cathedral architect

Jean Masunoury, “another third generation guardian of the

Cathedral.”

Restoring

beauty to public space

Restoring

beauty to public space

The AIA Board had called for participation of the

architect in local government in its 1951 report, noting “One

does not have to look very far to realize that the face of our land

is scarcely attractive except in those places where nature has not

been molested. There is no gainsaying that this unfortunate aspect

is attributable to the lack of participation of the architect in

the over-all and individual planning of the community as it spreads

increasingly over the landscape.”

With the end of the Korean War in 1953, the AIA intensified its

decades-long push for the removal of temporary buildings from the

Mall. “The erection of these temporary buildings, which began

at the time of World War I, was thought a practical necessity. Some

of these building are anything but temporary in construction being

of reinforced concrete.” Some argued that since the government

was renting space in Washington the elimination of these temporary

buildings would interfere with government economy. The AIA

countered by pointing out that dispersal of government departments

was a vital factor in making the nation safe from enemy attack. It

sought, as it had in 1901, to again return the Mall to the original

intent of a grand ceremonial space. Still, many of the buildings

would remain another 30 or more years before the Mall would be

cleared of them.

The Octagon stables become a repository of knowledge

Other issues were not ignored during the era. Hospital

design trends, school design trends, and new ideas in lighting,

structure, materials, and education were covered at convention

seminars and in special meeting in the AIA regions, and on January

8, 1954, the AIA opened and marked with an Octagon exhibition on

the theme “From Stable to Library,” its first space

devoted solely to library use. Within the envelope of the Octagon

stable, architects Howe, Foster & Snyder fashioned a two-story

library with all the amenities of research library, from fireplace

to comfortable reading chairs. It quickly became a favorite venue

for intimate meetings of AIA committees and boards, and a must stop

for students and scholars. Books from the former AIA library,

started in 1857, which had been sent to George Washington

University in 1916, were retrieved, and book cases from Richard

Morris Hunt’s Library were installed in the new

stable/library. An oil portrait of Richard Upjohn hung over the

fireplace of black Tennessee marble, and a marble bust of Thomas U.

Walter stood nearby. For the first time, the libraries of Richard

Morris Hunt, Frank Conger Baldwin, Donn Barber, Arnold Brunner, Guy

Kirkham, and Henry H. Saylor had a proper home.

In preparation

for a centennial

In preparation

for a centennial

A multi-year study of the AIA Commission for the Survey of

Education and Registration was finally published in 1954. Volume

One, weighing in at some 558 pages, and edited by Turpin C.

Bannister, was titled The Architect at Mid-Century. Volume

Two, at 270 pages, edited by Francis R. Bellamy, published

Conversations Across the Nation. Reviewer Richard M.

Bennett wrote that “the books stand as prerequisite reading

for those who demand reform and new form in the various phases of

our profession—the schools, registration boards, The

Institute, canons of practice, and relations to the building

industry as a whole,” and of Volume One “the book is not

meant for casual reading but as a landmark in the dissection of a

great profession.” No better or more accurate look at either

architectural education or registration has yet been published, and

the commission’s recommendations, contained at the end of

Volume One, are worth revisiting. Volume Two makes no claim to

factual information, but, in a series of conversations with

architects in major American cities, gives a compelling picture of

how they thought about themselves and the practice of architecture

at the mid-point in the 20th Century.

One major gift to the AIA in 1955 should be mentioned, the

Weyerhaeuser Company donation of the photographs, drawings and

publications of the White Pine Architectural Monograph

Series. Publication of the series, created and produced by

Russell Whitehead, began in 1915 and continued in one form or

another until 1950. In announcing the gift, purchased from Mrs.

Whitehead by Weyerhaeuser for presentation to the AIA, it was

described as consisting “largely or solely of working

drawings, measured scale drawings of mill work and trim in our old

colonial buildings. During the course of the preparation of these

monographs, they were photographed or illustrated, probably the

finest example of colonial architecture that has been known in this

country.” The intent of the series was to show that Colonial

detail could be exactly reproduced in white pine lumber, the result

was to record, in photographs, drawings and publications,

architecture of pre-Civil War America. Though not all the drawings

survive in the AIA Archives, the photographs are one of the finest

photographic collections of its type in existence.

In 1956, as

the Institute prepared to celebrate its centennial, President

George Bain Cummings could report that the membership of the AIA

had finally reached 10,972. John Burchard gave the keynote address

and it was announced that he had been commissioned to write a

Centennial History of the AIA “for the average American

citizen...to tell what Architecture means to them and what

architects have meant to them.” A photographic exhibition at

the National Gallery of Art, the unveiling of a plaque in New York,

issue of a US postage stamp, and a celebration in Washington were

promised. Alexander Robinson, Chancellor of the College of Fellows

and Chair of the Centennial Committee reported all these and more.

Slocum Kingsbury, of the Washington Chapter of the AIA, delivered

the official invitation to Washington, which Robinson had said

“belongs to everyone.” Kingsbury said “he could have

qualified that, that is, it belongs to everyone except the people

that live there. We don’t have a vote in Washington. We are

merely residents there. The city is run by your representatives.

But it is a lovely city.” And, it proved to be a lovely place

to celebrate a centennial, and a lovely celebration.

In 1956, as

the Institute prepared to celebrate its centennial, President

George Bain Cummings could report that the membership of the AIA

had finally reached 10,972. John Burchard gave the keynote address

and it was announced that he had been commissioned to write a

Centennial History of the AIA “for the average American

citizen...to tell what Architecture means to them and what

architects have meant to them.” A photographic exhibition at

the National Gallery of Art, the unveiling of a plaque in New York,

issue of a US postage stamp, and a celebration in Washington were

promised. Alexander Robinson, Chancellor of the College of Fellows

and Chair of the Centennial Committee reported all these and more.

Slocum Kingsbury, of the Washington Chapter of the AIA, delivered

the official invitation to Washington, which Robinson had said

“belongs to everyone.” Kingsbury said “he could have

qualified that, that is, it belongs to everyone except the people

that live there. We don’t have a vote in Washington. We are

merely residents there. The city is run by your representatives.

But it is a lovely city.” And, it proved to be a lovely place

to celebrate a centennial, and a lovely celebration.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page

|

AIA150 Rolling History  A Beginning, 1857-1866 A Beginning, 1857-1866 The Second Decade, 1867-1876 The Second Decade, 1867-1876 1877-1886: Westward and Upward 1877-1886: Westward and Upward 1887-1896: A Decade of Outreach, Inclusiveness, and Internationalism 1887-1896: A Decade of Outreach, Inclusiveness, and Internationalism Women and Women Architects in the 1890s Women and Women Architects in the 1890s 1897-1906: The AIA Moves to and Changes Washington 1897-1906: The AIA Moves to and Changes Washington The Institute's Influence on Legislative Policy The Institute's Influence on Legislative Policy At 50, the AIA Conceives the Gold Medal, Receives Roosevelt's Gratitude At 50, the AIA Conceives the Gold Medal, Receives Roosevelt's Gratitude Spinning a Golden Webb Spinning a Golden Webb 1909-1917: The Institute Comes of Age in the Nation's Capital 1909-1917: The Institute Comes of Age in the Nation's Capital 1917-1926: A New Power Structure: World War I, Pageantry, and the Power of the Press 1917-1926: A New Power Structure: World War I, Pageantry, and the Power of the Press 1927-1936: A Decade of Depression and Perseverance 1927-1936: A Decade of Depression and Perseverance The AIA in Its Ninth Decade: 1937-1946 The AIA in Its Ninth Decade: 1937-1946 1947-1956: Wright Recognition, White House Renovation, AIA Closes on 100 1947-1956: Wright Recognition, White House Renovation, AIA Closes on 100 The Tenth Decade: 1957-1966 The Tenth Decade: 1957-1966 1967-1976: New HQ and a New Age Take Center Stage 1967-1976: New HQ and a New Age Take Center Stage A New Home for the AIA in 1973; A Greener Home in 2007 A New Home for the AIA in 1973; A Greener Home in 2007 Diversity and the Profession: Take II Diversity and the Profession: Take II  'The Vietnam Situation Is Hell': The AIA's Internal Struggle over the War in Southeast Asia 'The Vietnam Situation Is Hell': The AIA's Internal Struggle over the War in Southeast Asia 1977-1986: Activism and Capital-A Architecture Are Alive at the AIA 1977-1986: Activism and Capital-A Architecture Are Alive at the AIA 1987-1996 Technology, Diversity, and Expansion 1987-1996 Technology, Diversity, and Expansion |

||

|

||

|

Image 1: Eero Saarinen won the competition for the St. Louis

Arch in 1947, the same year his father Eliel won the AIA Gold

Medal.

|

||