by Andrew Brodie

Smith

The socially turbulent 1960s and early ’70s were a time in the

U.S. when people tested and challenged inherited norms and

verities, and the AIA was not untouched by the spirit and mood of

the moment. Critical national and international events forced the

organization, which for 100 years had a reputation for being civic

minded, to reconsider its standing in the larger society. As social

movements percolated across the country, the AIA took a hard look

at itself and asked fundamental questions about the social role of

professional societies in general and of architects in particular.

Which social ills required the attention of the AIA? Were there

questions of conscience, non-professional in nature, that demanded

that the organization leverage its influence and prestige in

Washington? Was it right for members to ask the AIA to take

positions on issues beyond the expertise of architects and

planners? Did circumstances sometimes require it?

That

the political winds were shifting and the Institute was somewhat

out of step with progressive America first came into sharp focus

during an address by Urban League President and prominent civil

rights activist Whitney Young Jr. to the AIA 1968 Convention. Young

told delegates that, when it came to the nation’s critical

social issues, architects were “most distinguished” by

their “thunderous silence and complete irrelevance.”

Correct or incorrect in his assessment, Young had taken the gloves

off, and polite discourse no longer was the order of the day when

the social commitment of the profession was in question.

That

the political winds were shifting and the Institute was somewhat

out of step with progressive America first came into sharp focus

during an address by Urban League President and prominent civil

rights activist Whitney Young Jr. to the AIA 1968 Convention. Young

told delegates that, when it came to the nation’s critical

social issues, architects were “most distinguished” by

their “thunderous silence and complete irrelevance.”

Correct or incorrect in his assessment, Young had taken the gloves

off, and polite discourse no longer was the order of the day when

the social commitment of the profession was in question.

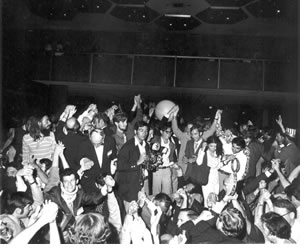

Inspired by the line of inquiry opened by Young and influenced by

left-wing, activist campus groups like Students for a Democratic

Society, architecture students also became more political in the

late ’60s, sometimes clashing with established professionals.

Students who had addressed prior AIA conventions had been brief and

deferential; now their tone was more strident. AIA Students

President Taylor Culver, an African-American, spoke to the 1969

convention in Chicago. Culver reassured nervous members, who had

seen on television the violent student protests nine months before

at the Democratic Convention held in the same city, that

architecture students weren’t about to tear down curtains or

throw chairs. Nonetheless, they would have their voices heard on

pressing national and professional issues. Angry about the

AIA’s neglect of some critical social problems, Culver

occasionally bordered on the confrontational while addressing the

gathered professionals: “What you as a generation have given

us, we are not exactly appreciative of.” And then later:

“I think you’ve failed and in fact if you turn your

backs, you will continue to fail.”

Expertise or conscience?

Civil rights, women’s liberation, political corruption,

the student’s movement, inflation, environmental concerns, the

energy crisis, of all the exploding social issues of the day that

occupied the AIA, none was more divisive than the Vietnam War. In

part, the division stemmed from a philosophical difference among

members as to whether an organization of architects should voice an

opinion on such a complex geopolitical issue. Some members felt

that Vietnam fell well outside the expertise of the profession and

that coming out officially against the war would squander the

influence and prestige of the Institute.

Others argued that it was simply wrong for the AIA to stay on the

sidelines of an issue of such national moral import. Moreover, they

believed that the organization could not effect change in the

domestic areas clearly within its purview—public housing, the

environment, energy, transportation, and design—while the

war’s price tag threatened funding for programs at home. As

Vietnam divided American society, it too split the AIA. The

Institute struggled with this internal conflict for years,

ultimately to no satisfactory answer.

1969: Commitment to “a humane

environment”

When, in 1966, the first anti-war rumblings were heard on the AIA

convention floor, U.S. combat troops (as opposed to military

advisers) had been in Vietnam for little more than a year. During a

discussion of other matters, Sidney Katz, AIA, rose to speak:

“The older order status quo is sitting very comfortably by

while the younger men are being picked off one by one and sent off

to a war to die and we certainly have not done enough to protest

this … War is hell; the Vietnam situation is hell, and it must

be removed at once.”

Three

years later, it was clear that these were the sentiments of many in

the architecture community. Chastened by the Whitney Young speech

the year before, pushed by its more politically progressive members

and students of architecture, and inspired by the social movements

building around them, the AIA took perhaps the most public stand in

its history on the pressing social problems of the day, passing

what it called the “National Priorities”

resolution.

Three

years later, it was clear that these were the sentiments of many in

the architecture community. Chastened by the Whitney Young speech

the year before, pushed by its more politically progressive members

and students of architecture, and inspired by the social movements

building around them, the AIA took perhaps the most public stand in

its history on the pressing social problems of the day, passing

what it called the “National Priorities”

resolution.

The resolution pronounced the AIA’s commitment to a

“humane environment,” to finding the money and political

will “needed to erase the shame of urban America.” And,

while not mentioning Vietnam by name, the resolution asserted

“that we have neither unlimited wealth nor wisdom, and that we

cannot sensibly hope to instruct other nations in the paths they

should follow when we are increasingly unable to demonstrate that

we know how to maintain a viable society at home.” As if

announcing that it had emerged from what Whitney Young had called

its “thunderous silence and complete irrelevance,” the

AIA later ran quotes from the resolution in major dailies

throughout the country.

Although the positions laid out in the National Priorities

resolution represented an unprecedented articulation of political

views for the AIA, they did not go far enough in the estimation of

many in the organization, particularly liberal members of the

Boston Society of Architects, the New York Chapter, and the AIA

Students. These groups as well as others made up an opinionated and

substantial faction within the organization that wanted it to come

out explicitly against the Vietnam War. Those persons holding the

most power nationally, especially the AIA Board of Directors, felt

differently. Taking an explicit and public anti-war position would

risk poisoning the waters between the AIA and the Nixon

Administration, hampering the effectiveness of the organization to

influence federal policy in areas that were more directly related

to the architecture profession.

1970: Increasing opposition

When the AIA convention convened in the summer of 1970,

public sentiment had turned increasingly against the war. The

courts martial of U.S. soldiers accused of responsibility for the

My Lai massacre had dominated the national news for much of March.

The invasion of Cambodia in late April sparked protests and riots

throughout the country, leading to the National Guard killing four

students at Kent State. It was in this environment that the AIA

Resolutions Committee was peppered with proposals for anti-war

resolutions from members and chapters wishing for consideration of

the issue on the convention floor. The Resolution Committee

consolidated these suggestions into one supplemental resolution,

which, for the most part, reiterated the sentiments of the National

Priorities resolution of 1969. While still making no specific

mention of Vietnam, the supplemental resolution did urge “the

President and Congress to reduce our military commitments and involvements

abroad to the absolute minimum consistent with our

nation’s security.” [italics added] This was a clear

attempt to appease the doves.

A call for reduced military commitments, however, wasn’t about

to placate the most anti-war of members. Stymied by the Resolutions

Committee and the leadership of the AIA, they introduced an

amendment on the floor. Member Richard Stein of New York read it to

the assembled: Resolved, that “the President and Congress of

the United States remove our military forces from Southeast Asia in

accordance with the schedule set up in the McGovern-Hatfield

Amendment, that is, immediately withdraw from Cambodia and complete

withdrawal from Vietnam by June 1971.” The issue the AIA

leadership had been so careful to avoid was now open for

consideration.

For

many influential people in the Institute, Stein’s amendment

was anathema. Such a direct repudiation of Nixon’s foreign

policy was to their way of thinking a foolhardy course. Relations

between the AIA and the Nixon Administration were cordial. Just

prior to the convention, Nixon had written a letter to then AIA

President Rex Allen in which he expressed his “warmest

admiration” for the AIA’s work on “the urgent needs

in communities across the country” and for its “civic

awareness and desire for human betterment.” Respect and

friendship between the White House and the Institute had ebbed and

flowed throughout the years and could never be assumed. If Nixon

was receptive to the organization, this represented an opportunity

that needed to be delicately leveraged. Outright support of a cease

fire on the part of the AIA would likely damage relations. Why

squander the prestige and goodwill of the Institute in Washington

on a foreign policy issue that architects were unlikely to impact

either way and that was beyond their expertise anyway?

For

many influential people in the Institute, Stein’s amendment

was anathema. Such a direct repudiation of Nixon’s foreign

policy was to their way of thinking a foolhardy course. Relations

between the AIA and the Nixon Administration were cordial. Just

prior to the convention, Nixon had written a letter to then AIA

President Rex Allen in which he expressed his “warmest

admiration” for the AIA’s work on “the urgent needs

in communities across the country” and for its “civic

awareness and desire for human betterment.” Respect and

friendship between the White House and the Institute had ebbed and

flowed throughout the years and could never be assumed. If Nixon

was receptive to the organization, this represented an opportunity

that needed to be delicately leveraged. Outright support of a cease

fire on the part of the AIA would likely damage relations. Why

squander the prestige and goodwill of the Institute in Washington

on a foreign policy issue that architects were unlikely to impact

either way and that was beyond their expertise anyway?

Board member and future (1972) AIA President Scott Ferebee, FAIA,

rising in opposition to Stein’s anti-war amendment, worried

out loud about what effect its passage might have on the fate of

the AIA’s efforts to get a professional architect appointed to

the position of Architect of the Capitol for the first time in 100

years. Nixon certainly was capable of retaliating by passing over

the Institute’s choice for the job, AIA Vice President George

White, FAIA. Opposition to Stein’s amendment may have been

partisan in nature and not exclusively born of a desire for the

Institute to pick its battles judiciously, evidenced by

Ferebee’s open support for Nixon’s Vietnam strategy.

“A number of us believe that the president’s action in

Cambodia was designed to get us out of Southeast Asia,” he

said on the floor of the Convention, “and it will have that

effect.”

Thanks in part to Ferebee’s arguments, the delegates defeated

the Stein amendment and passed the resolution that contained the

less confrontational language urging the reduction of military

commitments abroad. The issue, however, was not about to go away

and reared its stubborn head again during the following convention

in 1971.

1971: Boston and New York try

again

Not taking defeat lying down, The Boston Society of

Architects sent in a resolution to the National Convention the next

year, approved by a majority of its membership, which called for an

immediate end to the “massive destruction of the natural and

human environment in Indo-China.” Consistent with AIA

leadership’s reaction to a similar amendment the year before,

no such resolution made it out of committee. However, once again,

due to the politicking of the Boston architects and others, the

Resolution Committee took a small step in the direction of the

doves and introduced, now for the third time, a resolution

reaffirming the position of the AIA on national matters.

This time, the resolution was called the “Omnibus Resolution

on National Priorities,” and its authorship was credited to

the Boston Society of Architects, the New York Chapter, the AIA

Board of Directors, and the Resolutions Committee. The Omnibus

Resolution contained essentially the same general provision

regarding military commitments of the U.S. as expressed in 1970

with a slight modification, the word “accelerate” was

added, to indicate an added sense of urgency: President and

Congress should “accelerate the reduction of our

military commitments and involvements abroad [italics added].”

The resolution also urged “the rebuilding of areas ravaged by

war, most specifically the Indo-China area.”

Like

the year before, the most anti-war members found the new Omnibus

Resolution on National Priorities lacking for not specifically

calling for an end to the Vietnam War, and like the year before, a

member from New York (Mr. Frost), introduced an amendment from the

floor with stronger and more specific anti-war language. “The

recent disclosure in The Pentagon Papers of how our war policy was

made makes us more ashamed than ever of what has been going on so

long in Indo-China,” he said and then moved that the AIA

“urge the President to promptly initiate a unilateral and

total cease-fire.”

Like

the year before, the most anti-war members found the new Omnibus

Resolution on National Priorities lacking for not specifically

calling for an end to the Vietnam War, and like the year before, a

member from New York (Mr. Frost), introduced an amendment from the

floor with stronger and more specific anti-war language. “The

recent disclosure in The Pentagon Papers of how our war policy was

made makes us more ashamed than ever of what has been going on so

long in Indo-China,” he said and then moved that the AIA

“urge the President to promptly initiate a unilateral and

total cease-fire.”

Debate erupts on the floor

Mr. Bailey Ryan, AIA, (Kentucky): “Mr. President, I

don’t think there’s a man [sic] in this room that

disagrees with what is said in the resolution … We all feel

deeply about this; our guts are torn out about it. But I have seen

this war fought on this convention floor for three years with the

same resolution, exactly worded approximately the same way, and

every year we have the same debate and end up defeating it all

because the AIA are architects and we’re not militarists and

we’re not at all about showing the president of the U.S. how

to run the government on some other level not related to

architecture.”

Joe Siff, president of the AIA Students: “The amendment to

this resolution was brought up at a number of student caucuses and

I would like, therefore, to express the feeling of the majority of

the students here … Their feeling is that we are not

architects first, we are citizens first, and therefore it is wholly

appropriate to debate this issue on the floor of this

convention.”

Mr. Boone, member of the Board of the AIA: “At the risk of

being called a ‘hawk,’ I will point out this [a cease

fire] is totally unrealistic and impossible from a military

standpoint, and if someone passed such a resolution when those of

us were fighting World War II, I don’t think when we came home

we would have joined the AIA.”

Did we, or

didn’t we?

Did we, or

didn’t we?

After everyone had their say, the vote was taken. The

substitute resolution passed 69 to 55. After three years and much

acrimony, the AIA had finally taken an official position against

the Vietnam War. Or had it?

Upon announcement of the passage of the amendment, a delegate from

Southern California called for a written ballot on the question,

under which each delegate’s vote would be properly weighted to

take into account the number of members he or she actually

represented. The call for the written ballot received the required

vote of one third of the delegates. There would be a second vote.

Under the weighted ballot, the anti-Vietnam War resolution was

roundly defeated 365.81 to 736.61. The AIA had taken an anti-war

position, at least for a few minutes, and then took it away.

Moreover, the Convention took out the plank calling for the

rebuilding of war-torn Indochina. Mr. Virden of Mississippi, member

of the Board of Directors representing the Gulf States Region,

argued for the plank’s removal: “I find it singularly

amusing that in this whole resolution no mention is made of

veterans, of children of men that were killed over there, of

mothers and fathers and so forth, and yet we want to spend all the

money to take care of Vietnam.”

The issue resolves

itself

The next year would see yet another attempt to pass an

anti-Vietnam-War resolution. This one expressed “profound

concern … over the extension of the war.” However, with

no National Priorities resolution in 1972 on which to tack such an

amendment, those who offered the resolution needed a two-thirds

majority vote to get the Convention to consider it. They failed to

get the votes needed for consideration.

In January of 1973, the U.S., South Vietnam, and North Vietnam

signed the Paris Peace Accords, ending America’s combat role

in war and silencing the official AIA debate on the issue. The

course of events had resolved the problem for the Institute. The

organization would remain officially silent about the war. This was

as it should be according to some. To others it was a failure of

moral courage.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page