by Tony P. Wrenn, Hon. AIA The AIA’s first organizational decade, 1857-66, was

truncated by four years of Civil War into a decade of six years.

Yet, during those missing four years, one of the AIA’s

founding architects, Thomas U. Walter, completed his design and

construction of the iconic U.S. Capitol dome, which symbolized

then, and now, the supremacy of the Union. During its second decade, 1867-’76, the AIA attracted

members from beyond the New York, Boston, and Philadelphia area,

finding favor in the Midwest and upper South; held the first AIA

convention and published its proceedings; and oversaw the

establishment of the first AIA chapter and the first collegiate

schools of architecture. At the end of that decade, in 1876,

leadership passed from Richard Upjohn, in whose New York office the

Institute was founded in 1857, to Walter. Those two, with another

founder, Richard Morris Hunt, who followed Walter as president, led

the AIA to the threshold of the 20th century. As unlikely as it might seem that the AIA would survive its

earliest years without the perseverance of these three founders, it

is equally unlikely that it could have orchestrated or sustained

its Golden Age of the late 19th and early 20th centuries without

two men who became members during this third decade: Charles Follen

McKim, of New York, who became a Fellow in 1877, and Glenn Brown,

of Washington, D.C., who became a member in 1882. McKim, born in 1847, grew up in rural Pennsylvania, attended

Harvard for a year, then studied in Paris at the Ecole des

Beaux-Arts. He returned to this country in 1870 to work in the

office of Henry Hobson Richardson, who had become an AIA member in

1866. McKim founded his own firm in New York in 1872, which became

McKim, Mead and White, probably the best-known American

architecture firm of the 19th and 20th centuries. McKim moved, once

he was a member, almost immediately into leadership, being elected

AIA secretary for the term of 1877-1878. In the 20th century, he

would become AIA president. Brown, born in 1854 in Fauquier County, Va., spent much of his

childhood at his grandfather’s house, Rose Hill, in Caswell

County, N.C. His grandfather, Bedford Brown, a U.S. senator from

North Carolina, had opposed North Carolina’s secession from

the Union, though his father, Bedford Brown Jr., served as a

surgeon in the Confederate Army. After studying architecture at

MIT, Glenn Brown too became associated with Henry Hobson

Richardson—through Norcross Brothers in Worcester, Mass.,

Richardson’s master builders, where he served as draftsman and

paymaster. Brown opened his own office in Washington, D.C., in

1880. Both McKim and Brown survived into the Institute’s sixth

decade. McKim died in 1909 and, although Brown survived until 1932,

his AIA leadership ended in 1913 with an AIA reorganization. How

incredible it would have been to listen in on the conversational

flow of ideas when, during its third decade, these five, Upjohn,

Walter, Hunt, McKim, and Brown—often together with others who

were then members and whose names we recognize instantly

today—came together in AIA meetings and conventions. The

existing record indicates that architecture and the fledgling

organization seem never to have been far from their minds. Founders remembered Other founders would die during the decade. Of R. G. Hatfield,

who was AIA treasurer from 1860 to his death in Feb. 1879, the

trustees “gratefully call to mind the fact that all Mr.

Hatfield’s intercourse with its members has been marked by

uniform courtesy, and that his temperate counsel and consideration

had earned from them unqualified regard and respect.” Of all

the decade’s memorial statements, none is more touching than

that for Henry Fernback, who became a member in 1866 and died in

November 1883. Emlen L. Littell, who became a member in 1860, and

served as AIA secretary from 1862-64, wrote of him: “It is

rare indeed to find a man combining, as he did, such large

proportions of wit, kindness, energy, integrity & intellect. It

is rare to find an architect holding ground among the foremost of

his profession & practicing it actively and widely for so many

years having, as he had, not an enemy, but hosts of friends among

his employees, his clients and his professional friends. “He was devoted to his art, & his help in all matters

which tended to elevate it & further its higher aims, with his

ready sympathy for its practioneers, & especially for the

members of this Institute, were marked features in a character

illuminated by the genial glow of a warm heart.” These statements represent perhaps the greatest effect of the

AIA on the profession, for, even if it were only a

“gentleman’s club,” it changed the relations of

those gentlemen one to the other. Reminiscing at the 11th

Convention on Oct 18, 1877, E. C. Cabot, president of the Boston

Society of Architects, an AIA chapter, noted “Thirty years go,

when I commenced practice in this city, there were but half a dozen

architects, and several of these had been bred as engineers. There

was but little sympathy between them, their designs were carefully

guarded from each other, and their libraries kept locked. We had

few books of reference, and photographs were almost unknown. Twenty

years later ... About 50 assembled, some articles of association

were drawn up, a portion of those present signed them, and formed

the Boston Society of Architects ... The result of all this has

been to promote amongst us the most friendly professional

relations. As artists we cannot live without sympathy, and through

the earnest love of our work, and this cordial intercourse, we must

look for the elevation of our professional practice.” In fellowship, all for one

… The move westward Membership, which had long since included mid-Americans, reached

the West Coast in 1870 when Augustus Laver of San Francisco was

elected to Fellowship. Laver actively recruited new members,

writing in February 1878 about forming a chapter. At first, it was

to be a Pacific Coast chapter, but when it gave its first chapter

report, at the 16th Convention, October 25-26, 1882, in Cincinnati,

it was as the “San Francisco Chapter.” The American

Institute of Architects finally reached from coast to coast. Yet there were those who felt ignored and deprived of positions

of leadership. In 1884, some 100 architects from 14 Midwest states

met in Chicago and organized the Western Association of Architects

(WAA). Their’s was to be a classless membership, all were to

be Fellows, each a “professional person whose sole occupation

is to supply all data preliminary to the material, construction and

completion of a building and to exercise administrative control

over contractors supplying material and labor ... and the

arbitration of contractors stipulating terms of obligation and

fulfillment between proprietor and contractor.” At heart, the good of the

profession Up, up, and away Jenney had studied in Paris, choosing engineering at the Ecole

Centrale des Arts et des Manufactures, and not architecture in the

Ecole des Beaux-Arts. In spite of this, and in recognition of his

professional accomplishments, the AIA advanced him from Associate

to Fellow in 1886, one small step in dealing with competing

organizations and highrise buildings in its tricky architectural

future. Both would figure prominently in the AIA’s fourth

decade.

Upjohn died

Aug. 17, 1878, having survived barely into the Institute’s

third decade. Walter, in turn, barely survived into the fourth

decade, dying on Oct. 30, 1887. Hunt almost survived through the

fourth decade, dying July 31, 1895. These three, adult and

even-handed, yet ready to listen and open to ideas, must be given

credit for maturing the small—often uncertain of

direction—AIA.

Upjohn died

Aug. 17, 1878, having survived barely into the Institute’s

third decade. Walter, in turn, barely survived into the fourth

decade, dying on Oct. 30, 1887. Hunt almost survived through the

fourth decade, dying July 31, 1895. These three, adult and

even-handed, yet ready to listen and open to ideas, must be given

credit for maturing the small—often uncertain of

direction—AIA.

Upjohn’s memorial, after his death August 17, 1878, was

entered in the Minutes of the Trustees in several black-bordered

pages and read by AIA President Walter at the 12th Convention in

New York on November 13, 1878. Upjohn’s early life was noted,

as was his arrival in New York where he designed Trinity Church

(1841-46). “In the preparation of the designs for the new

edifice, the power and scope of the genius of Mr. Upjohn were first

made apparent, and from that time the success of his professional

career was assured. He dreamt,” Walter noted, “not of a

perishable home, who thus could build ... His works speak for him

all over the land and illustrate by graceful and enduring memorials

the taste and genius that placed him in the foremost rank of our

profession.” Upjohn’s activities, Walter said, had raised “the social

and moral standard of the Institute ... placing it in the advance

position it now occupies in the public estimation ... During all

these years he was untiring in his efforts to establish good

fellowship throughout the profession, to raise the standard of

practice, and to promote the progress of our art.”

Upjohn’s activities, Walter said, had raised “the social

and moral standard of the Institute ... placing it in the advance

position it now occupies in the public estimation ... During all

these years he was untiring in his efforts to establish good

fellowship throughout the profession, to raise the standard of

practice, and to promote the progress of our art.”

The decade was not an easy one economically. The absence of

work or personal tragedy often brought petitions to the Trustees

from members who could not pay their dues. One member, from

Cleveland, wrote on December 29, 1877, “pleading for an

extension of time in the payment of dues owing to prolonged

sickness in his family followed by the death of three of his

children.” The Secretary moved, and the Trustees approved

unanimously that “the sympathy of the Trustees by conveyed ...

that an indefinite extension of time for the payment of dues by

granted ... and that his name be retained on the rolls.” One

future president of the AIA was reported that year as delinquent

and, more shocking, as not having abided by the Bylaws in not

having “forwarded credentials of his professional work.”

Nevertheless both were overlooked—after all, three trustees,

including the AIA secretary, knew and endorsed him—and he was

advanced to Fellowship. Though the policy had already been breached

in that that member’s name was on the record, others were

protected for the trustees’ voted that the “list of

delinquents not be read into the minutes.” When, at the

February 15, 1877, trustees meeting, the treasurer reported a long

list of delinquents, a blank page was left in the minute book where

the secretary wrote in pencil “don’t insert names until

it is seen who pays.” Members experiencing difficulty were not

to be embarrassed in perpetuity. As the AIA

established contacts and its activities were reported in the press,

it received letters from all parts of the country, Canada, and

abroad, some 200 the trustees reported in 1884. The secretary sent

such documents as had been adopted by that time—a standard

contract, a schedule of charges, a pamphlet on competitions, the

constitution and by-laws, and perhaps convention proceedings. In

1881, when a letter came from a foreign architect asking for

information with a view to possible emigration, President Upjohn

noted caustically that it was not “one of the projects of the

Inst to form an Immigration Society.” Trustee Hatfield,

however, thought such letters should not be ignored, but be

referred to architects who had written the AIA seeking “first

class assistance.”

As the AIA

established contacts and its activities were reported in the press,

it received letters from all parts of the country, Canada, and

abroad, some 200 the trustees reported in 1884. The secretary sent

such documents as had been adopted by that time—a standard

contract, a schedule of charges, a pamphlet on competitions, the

constitution and by-laws, and perhaps convention proceedings. In

1881, when a letter came from a foreign architect asking for

information with a view to possible emigration, President Upjohn

noted caustically that it was not “one of the projects of the

Inst to form an Immigration Society.” Trustee Hatfield,

however, thought such letters should not be ignored, but be

referred to architects who had written the AIA seeking “first

class assistance.”

At the April 16, 1884, meeting, the St. Louis Chapter was

admitted, bringing the number of chapters to 11, and “papers

relating to the Bartoldi Statue of Liberty” were examined and

“laid over to the next meeting.” The Bartoldi Statue

Committee requested funds and after prolonged discussion at its

June 20 meeting. “It was moved, seconded, and voted, that in

view of the low state of the funds in the Treasury of the

Institute, that the request for funds be laid on the table.”

The AIA was not to be denied participation, however, for founder

and member Richard Morris Hunt designed the pedestal on which the

Statue stands. Many WAA

members were also members of the AIA, creating a problem that the

AIA would have to solve in its next decade or face stiff

organizational competition. Almost immediately, the WAA formed a

Southern Chapter and actively sought members in the South, an area

then sparsely represented in the AIA; offering immediate

membership, without question, to anyone already an AIA member.

Many WAA

members were also members of the AIA, creating a problem that the

AIA would have to solve in its next decade or face stiff

organizational competition. Almost immediately, the WAA formed a

Southern Chapter and actively sought members in the South, an area

then sparsely represented in the AIA; offering immediate

membership, without question, to anyone already an AIA member.

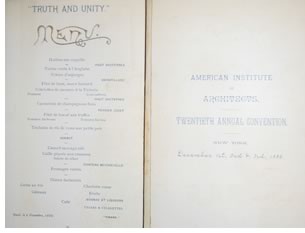

A. J. Bloor of New York, who had become an AIA member in 1861

and served 12 years as its secretary, attended the founding

convention and the second, which he described to the 20th AIA

Convention in 1886. He told of the election of a woman, Louise

Bethune of Buffalo, N.Y., to the WAA and reported “In private,

I was asked my views on the question of her admittance, and, as an

individual, I expressed myself in favor of it.” He was less

approving of Louis Sullivan, who “read an original and

charming paper of fine literary quality, (though personally I do

not altogether agree with all his deductions), on

‘Characteristics and Tendencies of American

Architecture.” Bloor concluded “The impression made upon

me during the performance of the mission you entrusted to me is

that the Association, equally with the Institute, has the good of

our art and of its professors at heart, and that it is our duty to

work cordially with it. The more closely we are united, the

speedier will be the realization of our common objects. Those who

are not with us are against us, and we have worked too long and too

hard to see complacency the fruit of what we have sown scattered

abroad.”

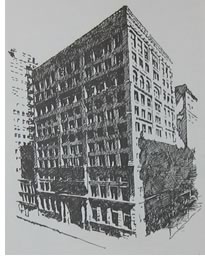

William LeBaron Jenney, of Chicago, who had become an AIA

member in 1872, participated actively in the migration of the

Institute westward and, in many ways, presaged its future as well,

by participating in organizing the WAA to challenge the national

supremacy of the AIA. The character of his architecture embodied in

the design and construction of his Home Insurance Building in

Chicago, 1884-85, would eventually challenge even the then

prevailing concept of building. Of skeletal construction, the Home

Insurance Building, initially 9 stories high, was raised to 11 in

1891. It has long been touted as the first “skyscraper,”

but there are other claimants. One is the New York Produce

Exchange, designed by George B. Post, who became a member of the

AIA in 1860. The Exchange, with a plaque that identified it as the

first skyscraper, was earlier, 1882-84, than Jenney’s building

in Chicago.

Copyright 2005 The

American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()