Dealing with the Depression, war, rescuing cities, and contemporary architecture

by Tony P. Wrenn, Hon. AIA

No previous decade in AIA history evidences the changing years as

does 1937-1946. In January 1937, a halt was called to a meeting in

the Octagon, so that a “radio machine” could be brought

into the room, the work table be covered with linen, and drinks

served. The directors awaited a broadcast from England, and

“what more fitting place to hear this broadcast than The

Octagon, teeming with historical associations.” It was, after

all, the very room and the very table, where President James

Madison had in 1815 signed the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of

1812 between Britain and America. There the directors sat,

“all listening to the firm, strong voice of a young King, a

thousand leagues away, renouncing the throne of a great

empire.”

Then, off with

tablecloth and back with ashtrays, papers, and discussion of AIA

issues. The Fifth Edition of the Standard Documents was approved,

and housing was discussed. Would the construction industry pattern

itself after the automobile industry and produce more trailers than

houses? Frederick Ackerman was afraid that was in our future and

wrote, “Lower income groups are continually on the move from

one area of decay and obsolescence to another.” If trailers

did indeed become a predominant method of housing, he asked,

“Precisely what problem is solved ...?”

Then, off with

tablecloth and back with ashtrays, papers, and discussion of AIA

issues. The Fifth Edition of the Standard Documents was approved,

and housing was discussed. Would the construction industry pattern

itself after the automobile industry and produce more trailers than

houses? Frederick Ackerman was afraid that was in our future and

wrote, “Lower income groups are continually on the move from

one area of decay and obsolescence to another.” If trailers

did indeed become a predominant method of housing, he asked,

“Precisely what problem is solved ...?”

Taking a stand

It was in 1937 that a decades-long battle of the AIA began. “A

Bill to revise the central part of the Capitol building at

Washington has again been presented in the Senate,” the Board

noted. It had been presented before, but tabled. The AIA had taken

no stand. Now that would change, but AIA committees were not of one

opinion. Edgerton Swartwout, of the AIA Committee on the National

Capital, stated that “The proposed extension is to provide

needed legislative accommodations, to give proper visual support to

the dome, and to replace the crumbling and defective sandstone of

the older portions with enduring material, white marble....This

extension and restoration will be of incontestable benefit to the

Capitol, to Washington and to the nation.” Officially the

Committee noted “it is not the function of the American

Institute of Architects to act as arbiter of such disputed

questions.”

Leicester B. Holland, chair of the AIA Committee on Preservation of

Historic Buildings, strongly disagreed. “To sacrifice the

present very beautiful composition which embodies the history of

American architecture, simply to make it more academically correct,

or just for a love of marble, seems to be frankly a piece of

parvenue vandalism. If this be Architecture, then Architecture in

America is not the goddess I have thought her, but a hussy who

would swap her honor for a new spring hat.”

The Institute,

meeting in Boston in June, decided that taking stands was one of

its functions, and stood with the preservationists. “Resolved:

That the American Institute of Architects in convention assembled,

expresses itself as opposed to any material alteration of the

central portion of the Capitol, either in form or material.”

Perhaps the report of the Committee on the Preservation of Historic

Buildings influenced some. Its Historic American Buildings Survey,

began in 1934, had seen employed, with federal funds, hundreds of

architects and draftsmen who had recorded a total of 2,700

structures “recorded in 13,700 sheets of measured drawings and

3,550 structures photographed in 16,150 negatives. In addition,

cards for some 2,700 structures still to be recorded are on

file.” HABS employed, it reported in 1939, a “continuous

average of 200 men.”

The Institute,

meeting in Boston in June, decided that taking stands was one of

its functions, and stood with the preservationists. “Resolved:

That the American Institute of Architects in convention assembled,

expresses itself as opposed to any material alteration of the

central portion of the Capitol, either in form or material.”

Perhaps the report of the Committee on the Preservation of Historic

Buildings influenced some. Its Historic American Buildings Survey,

began in 1934, had seen employed, with federal funds, hundreds of

architects and draftsmen who had recorded a total of 2,700

structures “recorded in 13,700 sheets of measured drawings and

3,550 structures photographed in 16,150 negatives. In addition,

cards for some 2,700 structures still to be recorded are on

file.” HABS employed, it reported in 1939, a “continuous

average of 200 men.”

Federal architecture and the employment of private architects for

its design and construction remained an aim. President Franklin

Roosevelt noted, in dedicating a Post Office in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.,

in October, “All over the United States there are scattered

the most terrible monstrosities of architecture perpetrated by the

Government on the people of the United States.” The AIA was

quick to applaud. President Charles D. Maginnis wrote “The

deplorable failure of ... this country to avail itself of the

artistic resources that have been at its command has long been a

source of regret and concern” to the Institute. He offered the

services of the AIA and Roosevelt responded acknowledging AIA

efforts, saying “We are of one mind that the architecture of

the United States Government should express the highest standards

of design and construction, be an influence on the cultural life of

America, and elevate the general standards of good

taste.”

Ask not …

In 1938, Francis P. Sullivan introduced an idea that

President John Kennedy later would make famous. “I believe

that it is our duty when these men ask The Institute what it has

done for them or what it will do for them, to tell them frankly,

‘You are missing the whole point of The Institute’s

purpose’. The real question is, ‘What can You and what

will You, through The Institute, do for the public good and for the

good of your profession?’”

In New

Orleans, the AIA gave its Gold Medal to Paul Cret and argued the

future of architecture. In presenting the award to Cret, Ralph

Walker echoed the idea suggesting that “symbols are evidently

more important than bread. Long after a people and their means of

sustenance is gone, stone rests upon stone and tells a story more

enduring than last year’s harvest or today’s

sowing.” At the same time he lauded Cret for being no copyist.

“His work ... is remarkable for three things—good

planning, individuality and good proportions. There are no loose

ends. The character of each building is complete within

itself.”

In New

Orleans, the AIA gave its Gold Medal to Paul Cret and argued the

future of architecture. In presenting the award to Cret, Ralph

Walker echoed the idea suggesting that “symbols are evidently

more important than bread. Long after a people and their means of

sustenance is gone, stone rests upon stone and tells a story more

enduring than last year’s harvest or today’s

sowing.” At the same time he lauded Cret for being no copyist.

“His work ... is remarkable for three things—good

planning, individuality and good proportions. There are no loose

ends. The character of each building is complete within

itself.”

By 1939, the Board reported architectural registration laws in 40

states and in the territories of Alaska, Hawaii, the Philippine

Islands, and Puerto Rico, with Arkansas and Alaska having adopted

laws that year, and seven of the remaining eight states attempting

to pass them.

Preparing for war

Even as the Depression lingered, conditions in Europe

added to the anxiety felt by architects. Outgoing President

Maginnis told the convention that “we should hold our course

in the belief that man has not lost his soul and that his world

will presently come again to sanity.” Incoming President Edwin

Bergstrom hoped “our country will not be involved by untoward

events beyond its borders,” but announced he would appoint a

preparedness committee to determine how to make the profession of

immediate service to the government.

Steps the Institute might take to meet the coming emergency were

discussed, among them a survey of some 14,000 architects and

offices, requesting “each to indicate the extent and character

of its practice, its personnel, equipment and facilities and the

type of work it knows it can best perform.” Still housed in

the Institute archives, the survey responses offer a mirror,

reflecting how architects viewed themselves and their work. The

Institute agreed to suggest representatives who might be asked to

work with the government on carrying out defense programs. It would

shortly appoint a special representative, with offices in The

Octagon, to report to the membership on government plans and

programs undertaken as the nation moved toward war.

Ever prescient, AIA Washington’s Air Raid Protection Committee

suggested to those who said it can’t happen here, “for

the sake of argument let us suppose that some day a far-flown plane

drops something more substantial than leaflets in the neighborhood

of one of our seaports, or on some inland industrial city.”

What then? Committee Chair Horace Peaslee suggested studying how

buildings “can be evacuated, safely and quickly,” and how

a bomb-proof shelter should be constructed, ventilated, and

serviced. In a series of roundtable discussions, the committee had

dealt, he reported, with adapting parking garages for shelters, the

type of shelters required, evacuation of citizens to camps in the

country, and the possibility of legislation requiring protection of

tenants and employees, with severe penalties for not providing safe

buildings.

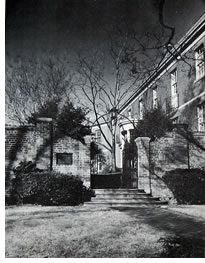

In a bit of

good news in 1940, the AIA Board announced awarding of a contract

to construct a new headquarters building behind The Octagon,

something approved in 1926. Dan Everett Waid, Dwight James Baum,

and Otto R. Eggers were the architects. Most of the money would

come from a trust fund established in 1936 by Waid, whose

“gifts aggregate almost four-fifths of its cost.” The

L-shaped brick building, two stories over a basement, would wrap

around the Octagon, not infringe on the existing garden, and give

the Institute not just the feel of an academic village, but, in

time, rental income as well.

In a bit of

good news in 1940, the AIA Board announced awarding of a contract

to construct a new headquarters building behind The Octagon,

something approved in 1926. Dan Everett Waid, Dwight James Baum,

and Otto R. Eggers were the architects. Most of the money would

come from a trust fund established in 1936 by Waid, whose

“gifts aggregate almost four-fifths of its cost.” The

L-shaped brick building, two stories over a basement, would wrap

around the Octagon, not infringe on the existing garden, and give

the Institute not just the feel of an academic village, but, in

time, rental income as well.

“War has been declared…”

With his first report, Washington representative Edmund R.

Purves confirmed that “The country is engaged in a program of

astronomical proportions and incidentally we are involved in a

shooting war.” In his second report, in December of 1941, he

wrote, “Since the last report was made to you, war has been

declared.” Purves said his office “is in a position to

help others avoid those embarrassing situations which may result

from action based upon inaccurate information,” but warned,

“We do what we can for the profession and we try to open as

many doors as possible through which the architects may enter.

However, it is not within our province to select architects for

jobs and we wish to emphatically call to your attention that on no

accord do we select or aid in the selection of architects.”

Later, before receiving his military commission, Purves wrote in

one of his last reports “This office is always ready to guide

those who come to Washington and can point the way and give you the

benefit of the contacts it has made and the relations it has

established. But very definitely your future lies in you own

hands.”

For a lack of “pithiness, ... aptness, ... freshness” in

his last reports, he apologized. “A sort of pall or a thin but

effective smoke screen appears to have been drawn across the news.

It is not the fault of the authors of the columns. The damp paw of

censorship is at work and those of us who are here in Washington

are driven to draw our own conclusions and make our own

surmises.” D. K. Fisher Jr., followed Purves as Washington

representative.

At its 1942 Convention in Detroit the Institute gave a special

award to Albert Kahn, who made even Ford and Chryslers assembly

plants handsome. “Exponent of organized efficiency, of

disciplined energy, of broad visioned planning ... Master of

concrete and of steel, master of space and of time, he stands today

at the forefront of our profession in meeting the colossal demands

of a government in its hour of need.” During the presentation,

in the Hotel Statler’s Grand Ballroom, when General William S.

Knudsen was praising Kahn’s contributions to the war effort,

“Sirens wailed—a practice blackout had begun in Detroit,

the brilliant lights of the Ballroom were gradually dimmed making

an unforgettable picture of the heroic figure of General Knudsen in

the reflected light of the shaded lamp before him.”

Setting the

Foundation

Setting the

Foundation

The Detroit award was probably the preliminary to an AIA Gold

Medal, but Kahn died a short time later. Just before his death he

had written the AIA “I cannot help but think that The

Institute would do a tremendous good to the profession if more

frequent recognition were given members for outstanding

work ...” He offered $10,000 to begin such a program, funds

which led to the 1943 formation of The American Architectural

Foundation, still active today, though chances are today few know

Kahn made it possible.

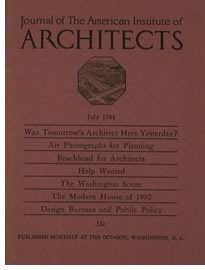

That same year, 1943, the Board of Directors sought a monthly

publication “which would be a more effective instrument of

expression than is possible within the limitations of the annual

appropriations ... The present Octagon was established in 1929 as a

bulletin of the Institute to transmit official notices to members,

to report activities of the Board and of the committees and in

other ways to advise on the activities of the organization.”

The Board asked the membership what it would like the new magazine,

which would take advertisements, to be. One question was

“Would you favor a change in form of The Octagon to,

say, Readers Digest or some other size?” Obviously

Readers Digest won, for the Journal of The American

Institute of Architects was that size when it began

publication in January 1944, with Henry Saylor as its editor.

The Washington representative continued his reports, noting the

need of the nation to deal with “those men who return to the

United States, like wreckage cast upon the shore ... That problem

was severe during World War I. Following World War II, gentlemen,

it is going to be a problem that you can’t even conceive

of.” He reported problems commissioned architects had to deal

with in the field: men who could not read or had never used a

telephone, and almost no one knew what an architect was, or what

one did.

The Washington representative proposed to deal with the problems,

and did so in print, “under the following headings: education;

what we choose to call the aesthetic phases of architecture; lack

of publicity and public recognition; and lack of professional

leadership.”

Soldiering

on

Soldiering

on

In 1944, the Institute was asked to abandon its convention, and

“that request was promptly and patriotically met.” Even

Board meetings were difficult, for “war activities and

military personnel have so crowded our principal cities.” In

April, 1945, at the 77th Convention in Atlantic City, “in

strict conformity with the requirements of the Office of Defense

Transportation ... [attendees] were limited to fifty.”

Still, the Institute continued. Lively and provocative articles

appeared in The Journal, as diverse as Edwin Bateman

Morris on “What Next for Architecture”: “While no

one can make predictions with accuracy, it is almost a certainty

that the argumentative phase of the Modern style is at an

end”; Henry Churchill on “What Shall We Do With Our

Cities?”: “A city exists for two things only; it is a

place in which people earn a living, and it is a place in which

people live and play. If a city fails in either...”; and Guy

Study on “Louis H. Sullivan—Fifty Years Afterwards”:

“His was a personal triumph mixed with futility; he was indeed

a brilliant meteor which shot across the firmament of art, but not

a planet by which American architecture may chart its

course.”

And in a gutsy move, the AIA Committee on Education asked Turpin C.

Bannister to compile a list, often reprinted, of “One Hundred

Books on Architecture.” It was suggested all libraries should

have these books. Twenty-five books were identified with asterisks

as a core collection for small libraries.

Striving for the future

In 1946, breaking with precedent, the AIA awarded the Gold Medal to

a deceased architect, Louis Sullivan, in, of all places, Miami

Beach. “He fought almost alone in his generation, lived

unhappily, and died in poverty,” the citation read. “But

because he fought, we today have a more valiant conception of our

art. He helped to renew for all architects the freedom to originate

and the responsibility to create.” The Sullivan Gold Medal,

Saylor would write in The Journal “brought assurance,

at a later session, that the Institute would strive in the future

to honor the living, year by year.” Some 600 attended, and the

convention ran overtime. There was peace, and the question of what

to do with it. Saylor concluded his report “And in six

early-morning flights of the big Douglas and Lockheed planes, well

over a hundred soared across to Havana to see what that city and

Cuba in general could offer to top off the Convention of

1946.”

At the beginning of the decade, the Board listened to Edward

abdicate. At the end of the decade, they discussed the atom bomb

and Oak Ridge, Tenn. There, “starting with 10,000 acres of

farmland, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, architects of Chicago and

New York, designed and built the city in less than a year, at a

cost of something less than $500,000,000. Oak Ridge now [October

1945] has a population of over 60,000—the fifth largest city

in its state. The architects laid out the plan as a group of 12

neighborhood communities, each with its school, shopping center,

church, and amusements. Centrally located, to serve the 12

neighborhood groups are the city hall, two large high schools and a

business district.”

Had the 20th Century finally arrived?

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page