by Tony Wrenn, Hon. AIA

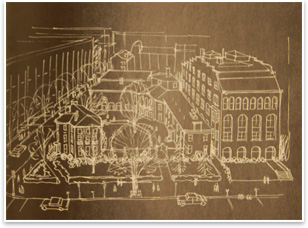

Times were

relatively good and administrative space tight for the AIA national

component, so leaders were planning a new national headquarters

building to “satisfy both physical and spiritual

functions—a building of special architectural significance,

establishing a symbol of the creative genius of our time yet

complementing, protecting and preserving a cherished symbol of

another time, the historic Octagon House.”

Times were

relatively good and administrative space tight for the AIA national

component, so leaders were planning a new national headquarters

building to “satisfy both physical and spiritual

functions—a building of special architectural significance,

establishing a symbol of the creative genius of our time yet

complementing, protecting and preserving a cherished symbol of

another time, the historic Octagon House.”

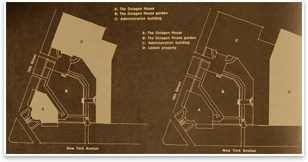

The initial design competition selection, by

Mitchell/Giurgola—a five-story red brick building that

featured a semi-circular mostly glass wall that embraced The

Octagon House and garden provided insufficient space and, after

acquisition of an adjacent 19th century building on New York

Avenue, the AIA asked for a new design. The AIA approved the

resulting 130,000-square-foot proposal at its 1967 convention, but

the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts thought it did not complement The

Octagon and rejected it and the follow-up revision.

Mitchell/Giurgola withdrew.

A new AIA selection committee, with Max Urbahn as chair and the

first, second, and third place winners of the initial competition

among its members—Romaldo Giurgola, I. M. Pei, and Phillip

Will Jr., respectively—began interviewing for a new architect.

They announced their selection May 14, 1969: The Architects

Collaborative (TAC), Walter Gropius’ firm in Cambridge, Mass.,

with architects Norman Fletcher and Howard Elkus in charge of

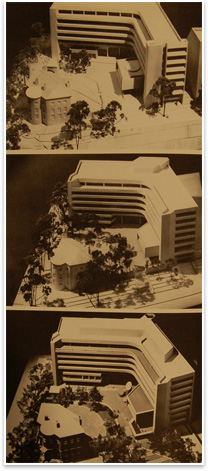

design and construction. Their design was ready for presentation to

the Commission of Fine Arts on May 15, 1970, and the commission

approved.

For the two-year construction phase, from January 1971 to March

1973, national AIA administration was housed at 1785 Massachusetts

Ave., NW, a 1910 building Jean de Sibour and now headquarters of

the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Even as the

Lemon Building, the Octagon Stable, and the 1940s Administration

Building were cleared away, restoration of The Octagon went forward

under the direction of restoration architect J. Everett Fauber Jr.

On March 12, 1973, the AIA began moving into the new headquarters

building at 18th St. and New York Ave., NW, behind The Octagon. In

a press release, the Institute noted “The new seven-story

headquarters building—which will be known as ‘The

Octagon’ [the official name of the historic Tayloe

mansion]—will house the Institute’s 100-person staff on

the first three floors. The remaining four floors will be available

for leasing.” Formal dedication took place in June, to which

that month’s issue of AIA Journal was devoted. The

press-release proclamation aside, the new building was rarely

referred to as The Octagon Building, generally becoming known

simply as the AIA Headquarters Building.

Even as the

Lemon Building, the Octagon Stable, and the 1940s Administration

Building were cleared away, restoration of The Octagon went forward

under the direction of restoration architect J. Everett Fauber Jr.

On March 12, 1973, the AIA began moving into the new headquarters

building at 18th St. and New York Ave., NW, behind The Octagon. In

a press release, the Institute noted “The new seven-story

headquarters building—which will be known as ‘The

Octagon’ [the official name of the historic Tayloe

mansion]—will house the Institute’s 100-person staff on

the first three floors. The remaining four floors will be available

for leasing.” Formal dedication took place in June, to which

that month’s issue of AIA Journal was devoted. The

press-release proclamation aside, the new building was rarely

referred to as The Octagon Building, generally becoming known

simply as the AIA Headquarters Building.

The times they were a-changin’

The decade had begun with a convention in New York in 1967 when AIA

President elect Robert L. Durham noted “We have finished our

‘first 100 years.’” Though the computer age had

arrived and was being touted as a great time saver and asset,

Durham suggested that the architect should be wary and control

technology, for “when we lose our interest in quality and

cannot give our first emphasis to design, we will no longer be

worth of the name AIA.”

Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York addressed the convention

telling conventioneers “I know of no more important group in

our country today than those assembled here in this gathering. Your

contribution as artists, as builders, as planners, as creators in a

country which will rebuild everything that has been built since the

days of George Washington in the next four years or duplicate what

has been built in the next 40 years is probably the most important

responsibility of any group of men and women in this nation ... You

are determining our future.”

Wallace Harrison won the AIA Gold Medal that year, and Rockefeller

was present for that ceremony as well. He and Harrison, whose

relationship as architect, client, and friends went way back more

than a quarter century obviously formed an obvious mutual

admiration society. Rockefeller had noted that Harrison was

“sensitive to new ideas and new concepts and yet he is not

swept along by every passing fad and fancy in architecture.”

He continued “I can’t help but recall an incident in

1934, I think it was, or ’35, when Wally and his associates in

the Rockefeller Center group had finished designing the central

building from a functional point of view, and then there was a

discussion as to whether this building should be draped in some

architectural style, and my father leaned strongly in this

direction, and Wally contained himself as long as he could and

finally exploded, ‘Damn it, Mr. Rockefeller, you just

can’t do that!’ And he didn’t.”

Harrison was eloquent in his acceptance of the Gold. “In spite

of our poets and prophets, we Americans have weaknesses and like

all humans have permitted the extension of slums, the over-building

of cities, the misuse of the skyscraper, and the automobile making

traffic impossible.

“By now

throwing out the bad parts of science and Victorian materialism and

mechanization, we also have permitted the dividing of races, the

division of the poor classes in the cities and the richer whites in

the suburbs. We have even stood by with small protests while our

sciences have developed the bombs.

“By now

throwing out the bad parts of science and Victorian materialism and

mechanization, we also have permitted the dividing of races, the

division of the poor classes in the cities and the richer whites in

the suburbs. We have even stood by with small protests while our

sciences have developed the bombs.

“But, born hopeful, we architects offer a better

future—new towns; new communities—where in the American

way, rich and poor, black and white, can live together with a new

transportation and a better environment . . . Governor Rockefeller

has shown how the government can use architectural

imagination.”

Rockefeller had been associated with Harrison for 35 years and

called it “one of the happiest and most rewarding association

of my life.”

“Few issues are outside the breadth of Wally Harrison’s

knowledge,” Rockefeller said. “Few subjects are beyond

the reach of his curiosity. Wally Harrison’s interests are as

wide as the world. And they range well beyond the necessities of

his professional discipline.

“And yet, it a wonderfully rewarding way, it is this very

largeness of mind, this wider vision, that elevates his

architecture to greatness ... I am reminded of the time Winston

Churchill said: ‘We shape our buildings; thereafter, they

shape us.’ If this is true, as I suspect it is, then Wally

Harrison has helped to shape our lives to the dimensions of

greatness.”

The AIA of the ’60s preserved . . .

A previous decision of the Institute to oppose the

extension of the West Front of the U.S. Capitol was being

restudied, since some maintained the AIA should not be involved. A

task force appointed by the Board studied the matter and disagreed,

reporting that “architects collectively, i.e., arts

commissions, service action groups, AIA chapters, or the Institute

itself, have an obligation to society to comment constructively on

public issues. Changes to the Capitol are in this category.”

The opposition was renewed “... since the decision to stop

adding to the Capitol must be made at some point, it should be made

now while the last remaining exterior portion of the original

Capitol can be saved as visible evidence of our

heritage.”

Ultimately—after

more than a decade of statements, congressional and committee

appearances, and a demonstration before the Capitol West Front and

a march up Constitution Ave.—the AIA prevailed. One still

looks from the Mall at a West Front that displays the genius of

architects Thornton, Latrobe, Bulfinch, and Walter and of landscape

architect Frederick Law Olmsted.

Ultimately—after

more than a decade of statements, congressional and committee

appearances, and a demonstration before the Capitol West Front and

a march up Constitution Ave.—the AIA prevailed. One still

looks from the Mall at a West Front that displays the genius of

architects Thornton, Latrobe, Bulfinch, and Walter and of landscape

architect Frederick Law Olmsted.

. . . And persevered

Few AIA convention speeches are more memorable, would be longer

remembered, or bring about more study and introspection than that

of Whitney M. Young Jr., at the 1968 Convention in Portland, Ore.

In starting a lengthy tutorial on civil rights, Young said,

“if I seem to repeat things you have heard before, I do not

apologize, any more than I think a physician would apologize for

giving inoculations. Sometimes we have to give repeated

vaccinations, and we continue to do so until we observe that it has

taken effect ... you are not a profession that has distinguished

itself by your social and civic contributions to the cause of civil

rights, and I am sure this has not come to you as any shock. You

are most distinguished by your thunderous silence and your complete

irrelevance.”

In the discussion period that followed the speech, Young continue

his offensive:

“But the fact happens to remain that out of the 11 hundred AIA

members in New York, only seven are Negro; out of the 8 hundred in

Chicago, only eight are Negro. I don’t know what the other 165

[chapters] look like, but you know. This is not enough ... You are

leaders in your communities, and you are not giving the quality and

the extent to the issue that can be given ... We want you to be

architects of a new morality, of a new national commitment, and

you’ve got to catch up because your forefathers in this field

didn’t do too well, so you have to run faster.”

Recognizing

the goring was deserved, AIA commissions, task forces, and studies

on integrating blacks, women, and other minorities into the

practice of architecture, and into the Institute, followed.

Recognizing

the goring was deserved, AIA commissions, task forces, and studies

on integrating blacks, women, and other minorities into the

practice of architecture, and into the Institute, followed.

AIA President George Kassabaum reported in 1969 “The

AIA’s national activities this year have tried to awaken a

collective social conscience in the profession ... we have urged

every chapter to destroy any racial barriers they may have

inherited from past generations ... But though we have tried to

show the way by our national policies and committee actions, your

community will not judge you or your profession by what the

national organization does ... Your community will reach its

decision by what you and your chapter do.”

A longer view elsewhere, too

In 1969, the AIA presented its first Twenty-five Year Award,

established “to recognize a distinguished design after a

period of time has elapsed in which the function, esthetic

statement, and execution can be reassessed.” The first award

went to New York City’s Rockefeller Center, “a project so

vital to the city and alive with its people that it remains as

viable today as when it was built.” The then-17-acre cluster

of 18 buildings on 4 city blocks, little changed, retains that

vitality still.

Among other awards that year was the AIA Allied Professions Medal

to John Skilling, principal-president of Skilling, Helle,

Christiansen, Robertson, structural engineers for the World Trade

Center.

Continuing its

long-established stewardship of monumental Washington, the AIA

broadened its opposition to District of Columbia planning in 1969

to include transportation. “Testimony opposing construction of

an improperly planned and developed freeway system for the District

and environs was delivered before the District of Columbia City

Council and the National Capital Planning Commission.” Though

the opposition was vocal and widely shared, the automobile proved a

powerful opponent. An open cut, which would have carried Interstate

66 across the Mall in front of the Lincoln Memorial was

successfully fought, but highways were still built that separate

Kennedy Center from its neighborhood, slash across the city in

front of the Capitol and cut, in open wounds, through every

quadrant of L’Enfant’s planned city. The AIA had been

able to protect the Mall, but even that protection would prove

temporary, and the next 30 years would bring changes that McMillan

Commission members could not have imagined.

Continuing its

long-established stewardship of monumental Washington, the AIA

broadened its opposition to District of Columbia planning in 1969

to include transportation. “Testimony opposing construction of

an improperly planned and developed freeway system for the District

and environs was delivered before the District of Columbia City

Council and the National Capital Planning Commission.” Though

the opposition was vocal and widely shared, the automobile proved a

powerful opponent. An open cut, which would have carried Interstate

66 across the Mall in front of the Lincoln Memorial was

successfully fought, but highways were still built that separate

Kennedy Center from its neighborhood, slash across the city in

front of the Capitol and cut, in open wounds, through every

quadrant of L’Enfant’s planned city. The AIA had been

able to protect the Mall, but even that protection would prove

temporary, and the next 30 years would bring changes that McMillan

Commission members could not have imagined.

In 1970, AIA President Rex Allen told the Institute “... it

was not until we saw the Earth’s portrait from the moon on TV

that it was brought home to one and all that our space ship is a

mighty small self-contained planet with limited resources and

limited area for waste disposal ... We had better become aware of

what we’re doing, as a nation, because we are the worst

offenders and as architects—don’t we have a peculiar and

particular responsibility. Aren’t we fond of claiming that we

are the designers of the man-made environment ... the future,”

he suggested, “ is not pre-ordained, it is what we will choose

to make of it.”

By 1971, the Institute had also undertaken computerization of

Institute records. “The system and an IBM 360 computer were

installed in October,” the Board reported. “As the system

is developed, its capacity for storage of data and facts about the

profession and the professionals will enable the Institute to

better serve each member and the interests of architecture.”

While the system proved successful in preserving and providing

business and professional records created from that time forward,

it has yet to develop a backward reach that will insure retention

of the Institute’s historical records about the AIA and about

architects.

Save the land; sprawl no more

In 1972 AIA President Max Urbahn reported a National Policy Task

Force Report, “call to action for the acquisition,

conservation, and design of our most precious natural

asset—land. It is land which is needed now for our future

generations ... I am not suggesting that architects alone are

equipped to deal with our national environmental crisis. But I

submit to you that we are better equipped than any other single

profession to guide the public debate on the critical questions

which will relate directly to the future quality of the built

environment.”

A year earlier

AIA President Robert F. Hastings had told AIA members: “Over

the years, the rhetoric on this subject has become a kind of

prideful ideology. By talking about it, you tended to demonstrate

that you were a deep thinker, well versed in the new philosophies,

one of the new breed of futurists. Yet, while you talked about

change, you privately felt unaffected by it. No longer ... The fact

is that we can no longer afford a system that discards cities and

towns and the people who live in them. We can no longer afford a

system that encourages waste, sprawl, neglect, and destruction. We

can no longer afford a system that consumes our resources faster

than we can replenish them ... The architect today, and the

Institute he [sic] directs, must now, I believe, plunge actively

into political life, enlist allies, swing votes, mobilize community

action, and take positions on issues that were once thought to be

outside our rightful area of concern.” It is almost as if

Hastings were suggesting a return to the AIA of 1900.

A year earlier

AIA President Robert F. Hastings had told AIA members: “Over

the years, the rhetoric on this subject has become a kind of

prideful ideology. By talking about it, you tended to demonstrate

that you were a deep thinker, well versed in the new philosophies,

one of the new breed of futurists. Yet, while you talked about

change, you privately felt unaffected by it. No longer ... The fact

is that we can no longer afford a system that discards cities and

towns and the people who live in them. We can no longer afford a

system that encourages waste, sprawl, neglect, and destruction. We

can no longer afford a system that consumes our resources faster

than we can replenish them ... The architect today, and the

Institute he [sic] directs, must now, I believe, plunge actively

into political life, enlist allies, swing votes, mobilize community

action, and take positions on issues that were once thought to be

outside our rightful area of concern.” It is almost as if

Hastings were suggesting a return to the AIA of 1900.

A lasting pledge to free-trade principles

In turn, 1972 also brought a challenge from the Justice Department.

Prior to 1970, the Ethical Standards of the AIA stated “An

architect shall not enter into competitive bidding against another

architect on the basis of compensation.” The Department of

Justice had contacted the AIA in 1968 noting that in its opinion

the standard was in restraint of trade and a violation of the

Sherman Antitrust Act. Because of the demonstrated concern of the

Institute’s own attorneys, no judicial action had been taken

against any member for violation of the standard since 1963.

Yet, on December 7, 1971, the Department of Justice advised the AIA

that they planned to file suit against the Institute for violation

of the Sherman Act, but offered to avoid litigation through

negotiation of a consent decree that the Institute would “not

have any ethical standard, rule, by-law, resolution, policy

statement, plan, program or course of action which prohibits

members from at any time submitting price quotations for

architectural services.”

After long discussion, the decree was approved by AIA members

assembled in convention. Settled for the moment, the question would

come back later whether the Institute had abided by the

decree.

A dearth of women in the profession

One resolution of the 1972 convention addressed to the

“Status of Women in the Architectural Profession,”

requiring the Institute to act positively to improve that status

and report to the convention on actions. Judith Edelman, who

reported, noted that the “intent of this sub-committee is not

to try to change the minds of those who believe that women should

not be architects, who would not want their wives or daughters to

be architects. That is clearly beyond the scope of the

committee’s effort. But there is a crucial difference between

the right to such personal beliefs and the right to discriminate

against those women who make the decision to be architects.”

Edelman reported that the percentage of women registered architects

seemed to hold steady at 1.2 percent of the total. “This may

be the lowest percent of any occupation short of steel workers or

coal miners.” She discussed other findings: “Unrefined as

they may be at this time, they are certainly enough to clearly

demonstrate that the alleged grievances are not all in the heads of

some paranoid chicks.”

Four years

later, in 1976, the Institute could announce a broad affirmative

action program aimed at ending professional discrimination against

women, making such discrimination a violation of professional

ethics. In announcing the program, AIA President Louis de Moll

called it “a commitment that all of us must consciously make

not merely as a matter of conscience, nor of compliance with

governmental or other directives. If we fail to respond, we will be

shortchanging not only a great many talented and dedicated

architects and future architects. We will be shortchanging our

whole profession.” Sixteen years after that initial

resolution, the Institute would celebrate—with exhibitions,

publications, and very public events—the centennial of the

election of the first woman to the AIA, Louise Blanchard Bethune,

in 1888. Although a great deal of progress has been made, women

still are under-represented among registered architects.

Four years

later, in 1976, the Institute could announce a broad affirmative

action program aimed at ending professional discrimination against

women, making such discrimination a violation of professional

ethics. In announcing the program, AIA President Louis de Moll

called it “a commitment that all of us must consciously make

not merely as a matter of conscience, nor of compliance with

governmental or other directives. If we fail to respond, we will be

shortchanging not only a great many talented and dedicated

architects and future architects. We will be shortchanging our

whole profession.” Sixteen years after that initial

resolution, the Institute would celebrate—with exhibitions,

publications, and very public events—the centennial of the

election of the first woman to the AIA, Louise Blanchard Bethune,

in 1888. Although a great deal of progress has been made, women

still are under-represented among registered architects.

The AIA at 109: poised for change

The American Bicentennial in 1976 seems not to have been

an AIA thing, though AIA President Louis de Moll declared that the

AIA had learned from it and, disturbed by what it learned, had

“taken that all-important first step—becoming

concerned.” That concern evidenced itself in many ways,

including vocal AIA support for passage of an Energy Conservation

and Production Act, participation in a National Forum on Growth

Policy, and sponsorship of AIA Regional Urban Design Assistance Teams

(R/UDATs).

“The problems we face,” de Moll said, “don’t

need to overwhelm us. They define challenges which a vigorous,

concerned people and a new national leadership should

welcome.”

Whether the nation, at the age of 200, was learning was a question

that could be answered in many ways, but the AIA, at the age of

109, certainly seemed to be.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page