by Tony Wrenn, Hon.

AIA

As the Teddy Roosevelt era segued into the Taft and then Wilson

administrations, the AIA found itself in the enviable position of

advisor in the formation of a federal council of fine arts, and

selection of the Lincoln Memorial and its site. During this Golden

Age, the AIA held its first West Coast convention, approached a

membership of 1,000, and inaugurated a feisty new Journal that took whacks at U.S.

public buildings policy right on its cover. And, sadly, the

Institute mourned the loss of one its most prestigious members just

before he was to receive the AIA’s second Gold Medal.

1909:

Toward a Fine Arts Commission

1909:

Toward a Fine Arts Commission

Just before the end of his term in January 1909, President Theodore

Roosevelt established by executive order a Federal Council of Fine

Arts. The AIA, in its turn, had been discussing a federal

“bureau of architecture” since 1875, and Executive

Director Glenn Brown and President Cass Gilbert often talked with

President Roosevelt about creating such a group. In meetings and

correspondence between the AIA and the president, the aims of such

a body were discussed and potential members were suggested. The

resulting Roosevelt Council of Fine Arts consisted of architects,

painters, sculptors, and a landscape architect. The executive order

included the AIA correspondence and White House responses and

directed that “the heads of Executive Departments, Bureaus and

Commissions govern themselves accordingly. Hereafter, before any

plans are formulated for any buildings or grounds, or for the

location or erection of any statue, the matter must be submitted to

the Council I have named and their advice followed unless for good

and sufficient reasons the President directs that it be not

followed.”

The council met at the Octagon to organize and held a formal

meeting on proposed locations for the Lincoln Memorial. The council

was then invited to the White House, where it reported in favor of

the Mall site, ending discussions of placing the memorial at any

other site. Inaugurated in March 1909, President William Howard

Taft issued an executive order on May 21, 1909, revoking the

Roosevelt order. Taft assured the AIA that he was in favor of such

a group, but felt it should be established by the Congress to have

the power it needed. Lobbying for congressional action began. On

May 17, 1910, Congress approved legislation establishing a United

States Commission of Fine Arts “to advise upon the location of

statues, fountains and monuments in the public squares, streets and

parks in the District of Columbia . . . and upon the selection of

artists for the execution of the same.” Later that year,

President Taft widened the commission’s powers by executive

order, giving it authority to advise on plans for public buildings

erected by the government in the District of Columbia.

1909: Honoring McKim

At the 1909 convention in December, President Gilbert urged members

to “nationalize your ideas,” suggesting that “We

have never held a convention on the Pacific Coast. It is time we

did.” The highlight of the 1909 Convention was to have been

the awarding of the Gold Medal, the AIA’s second, to Charles

Follen McKim, but McKim died before the medal could be awarded.

Still, the event was a glittering one. An exhibition of the work of

McKim, Mead and White was mounted at the Octagon. “This

exhibition shows that fitness, proportion, beauty, refinement,

study and striving at perfection, whether the problem be great or

small, are always evident,” noted a description of the

exhibition in the published proceedings of the “McKim Memorial

Meeting.” Tributes of respect came from around the country,

and President William Howard Taft; Senator Elihu Root; U.S.

Ambassador to Great Britain Joseph Hodges Choate; Cass Gilbert; and

American Academy in Rome President William Rutherford Mead

(McKim’s partner in the firm McKim, Mead and White)

spoke.

President Taft’s speech is remarkable for his recounting of

the inside story of how McKim saved the Mall when the Agriculture

Building, already under construction, was being built. Taft was

then Secretary of War, under Roosevelt, and involved in the

Agriculture Building controversy. He noted of McKim: “He was

sensitive, as I presume most geniuses and men of talent are, and he

suffered much as he ran against that abruptness and cocksureness

that we are apt to find in the neighborhood of Washington both in

the Executive and the Legislative branches. He was the last person

to give you the impression that he had either abruptness or

cocksureness, but I don’t know any one who, when he had set

his mind at a thing and had determined to reach a result, had more

steadfastness and manifest more willingness to use every possible

means to achieve his purpose than Mr. McKim.” Taft concluded,

“I am living in a house to-day [the White House] that has been

made beautiful by Mr. McKim. It is a house to which you can invite

any foreigner from any country, however artistic, and feel that it

is a worthy Executive Mansion for a great nation like this,

combining dignity and simplicity, and reflecting in all its lines

(it does to me) the dignity and simplicity of the art of Mr.

McKim.” (One who would understand McKim would do well to read

the speeches of Taft, Root, Choate, and Gilbert.)

In

presenting the Gold Medal, Gilbert said, “His monuments in

bronze and marble will long enrich his native land, his

benefactions, not measured alone in the standards of commerce, have

laid the sure foundation of even greater monuments in the hearts of

his countrymen. But it is not for these alone that we offer this

token of our praise and love. The award of this medal can add

nothing to his honor. Titles, nor decorations, nor medals, nor any

worldly thing can add to worth. Character and merit are intrinsic.

They are not conferred. Nothing we can do or say can add to their

sum. Nobility is of the soul.”

In

presenting the Gold Medal, Gilbert said, “His monuments in

bronze and marble will long enrich his native land, his

benefactions, not measured alone in the standards of commerce, have

laid the sure foundation of even greater monuments in the hearts of

his countrymen. But it is not for these alone that we offer this

token of our praise and love. The award of this medal can add

nothing to his honor. Titles, nor decorations, nor medals, nor any

worldly thing can add to worth. Character and merit are intrinsic.

They are not conferred. Nothing we can do or say can add to their

sum. Nobility is of the soul.”

Mead suggested—when accepting the medal and placing it in the

hands of McKim’s daughter—that if McKim were present, he

would say, “Whatever I have been able to accomplish in the

field of architecture has been from devotion to a great art and in

the interest of a noble profession. That my efforts have been

recognized by this representative body of American architects is a

reward which I shall always cherish.”

1910: Westward ho!

A major portion of the 1910 convention was given over to discussion

of railways and city development, with papers presented by

representatives of Wabash, Southern, Hudson and Manhattan, and

Baltimore & Ohio railroads, along with papers on transportation

to city development and on inter-urban stations and trolley traffic

in city streets. These papers were published under separate cover

as, “The Relations of Railways to City Development, Papers

read before the American Institute of Architects, December 16,

1909.”

That convention did indeed meet in California, the first to go so

far west. On January 17-21, members met at the Fairmont Hotel in

San Francisco. They then traveled to Palo Alto, Monterey, and Santa

Barbara between January 21 and 23, and ended in Los Angeles,

January 23-25. Returning home, many members went by way of the

Grand Canyon for a planned stop. President Irving K. Pond, in his

address to the convention in San Francisco, noted: “Our

American ideal need not, must not be expressed monotonously along

narrow lines, but must expand broadly under varied skies, under

climatic extremes, under varied ethnic and social impulses unified

by one American spirit. This must be if we are to be true to our

aesthetic ideal. California is one phase of America, as New England

is another, as Manhattan is another, these phases are to be

harmonized and not confused, to be nurtured and developed and not

swept aside for some manifestation of exotic growth. The American

Institute of Architects is deeply concerned in the ethics of

business and the profession, in the science of business and the

profession, but its passion must be for the beauty which inheres in

architecture.”

Also announced at the 1910 convention were the congressional

approval of the Commission of Fine Arts, and the appointment of

members Daniel Burnham, Cass Gilbert, Daniel C. French, Thomas

Hastings, Frank D. Millet, Charles Moore, and F. L. Olmsted Jr.

(all AIA architects or Honorary AIA members). Convention attendees

approved the awarding of the AIA Gold Medal to George Browne Post

at the next convention.

1911: Widespread influence and

presidential praise

In 1911, AIA membership was approaching 1,000, but its press

indicated far greater influence than that number would indicate.

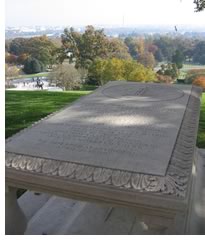

For instance, L’Enfant’s memorial, finally unveiled at

Arlington Cemetery on May 22, 1911, at 4.p.m. in ceremonies

arranged by Brown and various committees, Leslie’s, Collier’s,

the National Press Club, and others were invited to attend and

notified Brown they would. President Taft was on hand, as were

students from the Colonial School for Girls in Washington. The

school’s headmistress wrote Brown that, “It was an

occasion they will never forget.” The impressive tabletop

marker erected over the grave carried the L’Enfant Plan for

Washington and a legend noting “Pierre Charles

L’Enfant/Engineer, Artist, Soldier/ Under the direction of

George Washington/Designed the Plan for the/Federal City . .

.”

The

1911 Convention was highlighted by the presentation of the AIA Gold

Medal to George Browne Post at the New National Museum in

Washington on the evening of Dec. 13, 1911. AIA President Pond

opened by introducing Post, stating, “George B. Post joined

the American Institute of Architects in 1860, and for fifty years

he has given his time and talents to building up and improving the

standard of art, looking to the benefit to the public and the

improvement of the artist; his efforts have been one of the factors

in bringing the architect, sculptor and painter together in an

effort to produce harmony in the combination of the

arts.”

The

1911 Convention was highlighted by the presentation of the AIA Gold

Medal to George Browne Post at the New National Museum in

Washington on the evening of Dec. 13, 1911. AIA President Pond

opened by introducing Post, stating, “George B. Post joined

the American Institute of Architects in 1860, and for fifty years

he has given his time and talents to building up and improving the

standard of art, looking to the benefit to the public and the

improvement of the artist; his efforts have been one of the factors

in bringing the architect, sculptor and painter together in an

effort to produce harmony in the combination of the

arts.”

President Taft, in his address, said, “I count it a very

fortunate circumstance in the profession of the architect that

there is some material, definite printed certificate of excellence.

They do not have any such provision at the bar that I know of

(laughter), or in medicine (laughter), or even among clergymen

(laughter): you have to gather such certificates of excellence as

you can from the uncertain thing we call the public opinion of the

profession. But in architecture, apparently, they have the virtues

so much more solid and their standing in their profession so much

more certain that they classify them as golden, and silver and

copper (applause and laughter). I am glad to be here and to lend,

both personally and officially, such weight as I may (laughter) to

the importance and the appropriateness of this occasion of the

rewarding of a man who for 50 years has labored to elevate his

profession, and who has had the good fortune to live as long as Mr.

Post has lived, to see his profession develop in this country and

to feel that much of it has been due to his effort

(applause).”

M. J. J. Jusserand, the French ambassador, gave the major address,

saying of Post: “From first to last, he has acted upon a

principle which may appear simple enough when expressed, but is not

of such an habitual application as to have become banal; the

principle that a building is not an abstract composition raised

mid-air for the delectation of fleshless spirits, but is a reality

holding fast to the ground, to a particular sort of ground, in the

midst of definite surroundings, in view of certain uses, with all

of which it must agree: there must be harmony.” Post’s

response to these and to President Pond’s official

presentation, was a scant 100 words that included: “This medal

will be guarded always as a most precious treasure; its value will

be enhanced by the memory of this night and the circumstances of

its presentation.”

1912: The Institute faces a new

world

1912 proved momentous for the Institute: The AIA finally accepted

H. Van Buren Magonigle’s design of the seal that is still in

use, approved the end of publication of the Quarterly Bulletin (which had

begun publication in 1900), and in its stead approved publication

of a monthly Journal of the

American Institute of Architects. The Board of Directors

could also report that the Fine Arts Commission had recommended and

the Congressional Committee for the Lincoln Memorial (of which Taft

was the chair) had formally selected Henry Bacon’s design and

the Park Commission-recommended site for the Lincoln Memorial. The

first issue of the Journal

carried an article on the Lincoln Memorial with drawings, text, and

a summary of AIA efforts to secure the design on the Mall

site.

Evidently,

though, not everyone was enamored of the Bacon design. The Illinois

Chapter was one of the most vocal against it, noting that the

design was not a product of its time and had no “connection

historically, nor from the standpoint of Democracy with the work of

Abraham Lincoln, nor with his life, his Country or his time; but

suggests rather the age of Pericles.” The resolution adopted

by the chapter on Jan 14, 1913, also noted: “Said design is of

classic inspiration bearing a very close resemblance to Greek

Temple Architecture of the Doric period; and ... A large bronze

likeness of our beloved martyred President is to be placed in the

midst of said Greek Temple suggesting of Lincoln a ‘Greek

Deity.’” The resolution approved the site, but suggested

rethinking the design. Nevertheless, the House approved a joint

resolution on the Memorial on January 29, 1913, which President

Woodrow Wilson signed on February 1, accepting both Bacon’s

design and the Park Commission site.

Evidently,

though, not everyone was enamored of the Bacon design. The Illinois

Chapter was one of the most vocal against it, noting that the

design was not a product of its time and had no “connection

historically, nor from the standpoint of Democracy with the work of

Abraham Lincoln, nor with his life, his Country or his time; but

suggests rather the age of Pericles.” The resolution adopted

by the chapter on Jan 14, 1913, also noted: “Said design is of

classic inspiration bearing a very close resemblance to Greek

Temple Architecture of the Doric period; and ... A large bronze

likeness of our beloved martyred President is to be placed in the

midst of said Greek Temple suggesting of Lincoln a ‘Greek

Deity.’” The resolution approved the site, but suggested

rethinking the design. Nevertheless, the House approved a joint

resolution on the Memorial on January 29, 1913, which President

Woodrow Wilson signed on February 1, accepting both Bacon’s

design and the Park Commission site.

1913: The rise of the

Journal and Glenn Brown’s new legacy

1913 brought two events mourned by many. One was a change in

governance policies that led to the position of secretary to be

elected by the AIA Board, which effectively removed Glenn Brown

from office. A long resolution, prepared by a committee co-chaired

by Gilbert and William A. Boring, noted that the Institute was

“deeply impressed with the notable achievements and the

faithful services of Mr. Glenn Brown, who for fifteen years has

been its devoted Secretary and Treasurer.” The resolution,

which recounts events of the past 15 years that Brown either

initiated or to which he was central, was unanimously carried. 1913

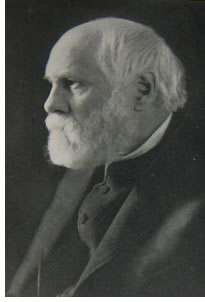

was also the year that Charles Babcock, the last of the original 13

founders who met in Upjohn’s office on February 23, 1857,

passed away. The resolution on his August 27, 1913, death noted

“his death marks the passing of a great period which must ever

be of peculiar interest and value to American architects, for it

illustrates how high ideals and confident endeavor can bring order

out of chaos, confidence out of suspicion, and great accomplishment

by reason of character and integrity.”

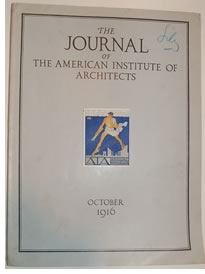

1913 marked the first year of the publication of the Journal, which was to become one

of the most influential publications in its field. It published the

minutes of the Board of Directors, reproduced superb graphics, and

carried provocative articles, all with a point of view. Even the

cover was used to editorialize. For instance, the cover of the

February 1916 issue, introduced in bold type an article on

“Our Stupid and Blundering National Policy of Providing Public

Buildings, Showing how the city of Washington is being marred by

the erection of office buildings for rental to the Government at

rates based upon inflated values.” It was a topic the magazine

would return to again and again. The cover of the May 1916 issue

noting, in equally bold type, “Only a determined national

effort, led by unceasing patience, directed by an intelligent

appreciation, and inspired with the vision of Washington and

Jefferson, can save the nation’s capital from the

architectural desecration which has already wrought an injury

greater than the nation knows.” Charles Harris Whitaker, its

editor, hired Clarence Stein as an associate editor and published

both Lewis Mumford’s first article and the last written work

of Louis Sullivan. Along the way, dreamy photographs of New York

and New Orleans, drawings and photographs of colonial mansions, and

news of current events made their way into the magazine.

Glenn

Brown’s relationship with the Octagon did not end in 1913, for

he was hired almost immediately to do something that he had begun

years before: He wrote about the Octagon and hired Frances Benjamin

Johnston to photograph it. The AIA asked Brown’s firm (in

which his son Bedford Brown was a partner) to make measured

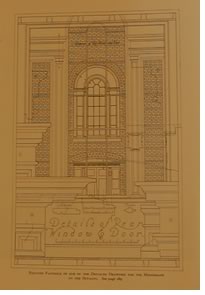

drawings of the house. The drawings were published in a monograph

with photographs of the house and its furnishings, and a history

penned by Glenn Brown. It is not praising the drawings too highly

to note that they established standards for such measured drawings;

standards which would be picked up a decade later when the Historic

American Buildings Survey began.

Glenn

Brown’s relationship with the Octagon did not end in 1913, for

he was hired almost immediately to do something that he had begun

years before: He wrote about the Octagon and hired Frances Benjamin

Johnston to photograph it. The AIA asked Brown’s firm (in

which his son Bedford Brown was a partner) to make measured

drawings of the house. The drawings were published in a monograph

with photographs of the house and its furnishings, and a history

penned by Glenn Brown. It is not praising the drawings too highly

to note that they established standards for such measured drawings;

standards which would be picked up a decade later when the Historic

American Buildings Survey began.

The Octagon Monograph,

issued in a portfolio containing some 30 folio-sized drawings, was

promoted by the Journal,

which noted, “One cannot enter it without unconsciously

peopling its rooms with the gracious men and women of that

day—there may come even a lingering regret over the changes

which seem to have made that life no more than a memory—and

there will surely come the devout wish that the whole may be

jealously guarded and preserved as an inspiration to future

generations.”

1916: The “winds of

war”

In 1916, the Board of Directors could report a membership of

1,432 but note that “The architectural profession is at best a

small one numerically, and the membership of the Institute does not

as yet comprise a majority of the members of the profession. Until

that point has been reached and passed, the Institute cannot speak

with complete authority in a country where majority rule

governs.”

Whatever the state of practice in this country, the coming

conflagration could not be ignored. President Mauran recalled that,

“At the last two conventions my predecessor touched our hearts

and stirred our every sympathy with his word-pictures of the

tragedy being enacted across the sea. Today the tragedy still holds

sway, but we must look beyond that moment of devout thanksgiving

when peace shall have rung the curtain down, to the day when

war-weary Europe shall confidently demand not our sympathy alone

but our sympathetic constructive cooperation. And on that day let

us not be found unprepared to take up the responsibilities which

belong to us by right and by training as citizens of the

world.”

Those responsibilities would arrive with force in 1917.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page

|

AIA150 Rolling History  A Beginning, 1857-1866 A Beginning, 1857-1866 The Second Decade, 1867-1876 The Second Decade, 1867-1876 1877-1886: Westward and Upward 1877-1886: Westward and Upward 1887-1896: A Decade of Outreach, Inclusiveness, and Internationalism 1887-1896: A Decade of Outreach, Inclusiveness, and Internationalism Women and Women Architects in the 1890s Women and Women Architects in the 1890s 1897-1906: The AIA Moves to and Changes Washington 1897-1906: The AIA Moves to and Changes Washington The Institute's Influence on Legislative Policy The Institute's Influence on Legislative Policy At 50, the AIA Conceives the Gold Medal, Receives Roosevelt's Gratitude At 50, the AIA Conceives the Gold Medal, Receives Roosevelt's Gratitude Spinning a Golden Webb Spinning a Golden Webb 1909-1917: The Institute Comes of Age in the Nation's Capital 1909-1917: The Institute Comes of Age in the Nation's Capital 1917-1926: A New Power Structure: World War I, Pageantry, and the Power of the Press 1917-1926: A New Power Structure: World War I, Pageantry, and the Power of the Press 1927-1936: A Decade of Depression and Perseverance 1927-1936: A Decade of Depression and Perseverance The AIA in Its Ninth Decade: 1937-1946 The AIA in Its Ninth Decade: 1937-1946 1947-1956: Wright Recognition, White House Renovation, AIA Closes on 100 1947-1956: Wright Recognition, White House Renovation, AIA Closes on 100 The Tenth Decade: 1957-1966 The Tenth Decade: 1957-1966 1967-1976: New HQ and a New Age Take Center Stage 1967-1976: New HQ and a New Age Take Center Stage A New Home for the AIA in 1973; A Greener Home in 2007 A New Home for the AIA in 1973; A Greener Home in 2007 Diversity and the Profession: Take II Diversity and the Profession: Take II  'The Vietnam Situation Is Hell': The AIA's Internal Struggle over the War in Southeast Asia 'The Vietnam Situation Is Hell': The AIA's Internal Struggle over the War in Southeast Asia 1977-1986: Activism and Capital-A Architecture Are Alive at the AIA 1977-1986: Activism and Capital-A Architecture Are Alive at the AIA 1987-1996 Technology, Diversity, and Expansion 1987-1996 Technology, Diversity, and Expansion |

||

|

||

|

Image 1: Charles Babcock, the last surviving founder of the

American Institute of Architects, attended the 50th anniversary

celebration of the AIA’s existence in 1907. He died in

1913.

|

||