by Tony P. Wrenn, Hon.

AIA

“Architecture as an Art” was the theme in Washington, on

May 11, 1927, as AIA President Milton Medary opened the 60th AIA

Convention:

“The architect hears everywhere, ‘Let us have a new

architecture, an American architecture; let us have done with the

dealers in classic and medieval forms; let us try something truly

American!’ . . . This is plain sophistry. Just as well say:

‘Let us have an entirely new written language, as well as the

physical one; let us stop using the words used by Shakespeare and

express our thoughts by sounds never heard before; and let us be

entirely individual and no two of us use the same sounds!’ . .

. This sophistry is due to the confusion which fails to

differentiate between using the soul and mind of Shakespeare as our

own and using the words with which he expressed the thing born in

his own spirit; words which have become exquisite with every

delicate shade of meaning only because men have long used them and

understand them. Without them the power of beautiful expression

would disappear. The written language is a living changing thing,

however, and slowly and surely, as Doric architecture became Ionic,

and Roman Romanesque, and Romanesque Gothic, the English of Chaucer

became that of the sixteenth century, of the eighteenth century,

and of the present day.

“Let us,

then, in looking to the future close our eyes to the changing

multitude of surface manifestations and look below the surface for

the roots out of which they spring, and let us search among the

roots for those which are universal and have abiding

character.”

“Let us,

then, in looking to the future close our eyes to the changing

multitude of surface manifestations and look below the surface for

the roots out of which they spring, and let us search among the

roots for those which are universal and have abiding

character.”

And back home, a tough

client

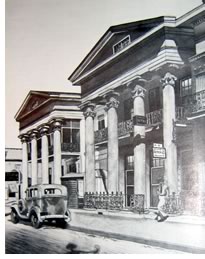

Medary’s office was in The Octagon, which was

purchased by the AIA in 1902, four years after it leased the house

and moved its headquarters there. The complex of mansion, stable,

smokehouse, and garden gave the AIA enormous prestige, for many

considered it to have architectural and historical importance

second only to the White House as a Washington residence. It had to

be preserved, and its open space not trespassed upon.

By 1926, The Octagon was suffering from AIA use, which generated

the weight of staff, visitors, library, and files the former

residence had not been constructed to support. The AIA had begun

studying possible construction of offices behind the historic

building even before it purchased the property. In 1906, it asked

Charles F. McKim to design such a building, and Glen Brown had

produced drawings for one in 1907. By 1914, as Brown made measured

drawings of The Octagon, published as a monograph in 1915, a

building committee was seeking new plans. Brown and Bedford Brown,

his son, did drawings for a new building in 1912. Henry Bacon,

Charles Platt, and Howard Van Doren Shaw all did plans in 1922, as

did George Nimmons and Dan Everett Waid in 1924.

In 1927, Waid, then chair of The Octagon Building Committee, came

to the AIA convention prepared. A handsomely designed 55-page book

detailing the history of designs for The Octagon property had been

printed, and models of two schemes recommended by the Building

Committee were ready. When the “Development of The Octagon

Property” theme was introduced, Waid chastised, “You are

fine and I love you all, but you are very bad. You are one of the

worst clients I ever saw. I have in the course of my short

experience had to do with all kinds of clients, as you have, and

the next time I hear you, any of you, complaining about some …

client who has given you a lot of trouble by changing her mind or

being slow in making up her mind, you will not get so much sympathy

as I would have given you some time ago.”

Dozens of architects, score of

opinions

A lengthy discussion followed. How much of the property could be

built upon? How high should the new building be, and of what

design? Should it contain offices and auditorium? Could the stable,

which had housed several horses, house more than the Institute

secretary’s car? And which would be more disruptive to life in

The Octagon and adjacent offices, the sounds of horses or of

automobiles? New Yorkers found the sounds of automobiles more

soothing and less disruptive. Others were less certain they wanted

to see a garage “in the midst of The Octagon

property.”

All agreed though that “The Octagon ... including the smoke

house and stable, be preserved as far as possible intact,” and

that the garden was included in the untouchable complex. A scheme

was finally approved to build offices and library, but with the

Depression at hand, construction was once more delayed.

One immediate

result of the 1927 convention, which voted to sell the AIA Press

and Journal, was the loss

of the beauty, popularity, and innovative design of the Journal and of publications of

the Press. Neither had been a moneymaker, but the Journal had proven so popular and

useful to the membership, and to others interested in architecture,

that having no publication was not even considered. The Journal was replaced by The Octagon, “A Journal of

The American Institute of Architects,” a no-nonsense

publication, without illustrations or advertisements, which carried

news of the profession. In 1932, it became the sole publication of

the Institute, replacing even the convention proceedings, which had

been published annually since 1867.

One immediate

result of the 1927 convention, which voted to sell the AIA Press

and Journal, was the loss

of the beauty, popularity, and innovative design of the Journal and of publications of

the Press. Neither had been a moneymaker, but the Journal had proven so popular and

useful to the membership, and to others interested in architecture,

that having no publication was not even considered. The Journal was replaced by The Octagon, “A Journal of

The American Institute of Architects,” a no-nonsense

publication, without illustrations or advertisements, which carried

news of the profession. In 1932, it became the sole publication of

the Institute, replacing even the convention proceedings, which had

been published annually since 1867.

Even while backing away from an illustrated publication,

conventioneers still found time to discuss the importance of

design. In 1928, honor awards were discussed, and several chapters

reported honor-award programs. The idea that developed was to award

at the chapter level and, from local winners, select recipients of

the national honor awards. It would be another two decades, though,

before a national Honor Awards Program began. The need to impress

the importance of the Institute on new members was also discussed,

and an Admission Ceremony considered. The Washington State Chapter,

it was reported, found such a ceremony beneficial, in which a

public reading of The Principles of Professional Practice

was central. Such a ceremony, easily arranged on the local level,

was not as simple to adopt on the national level.

Hard times create good

leaders

Even before the Depression, finding work for architects was a major

topic of conversation—and community leadership was the

suggested solution to overcome the perception that one actually

needed doctors and lawyers, but one could build without an

architect. In 1928, the Board of Directors suggested in “The

Architect and the Community—A Criticism” that this

perception was being fostered by architects themselves. The Board

believed, the paper stated “that the architect is guilty of

neglecting his community. As a professional group, organized or

unorganized, he seems to give little or no attention to the civic

progress of his own town or city. A charge of disregard of

community welfare cannot be made against the doctors. They are

active in their field, as it affects the health of the people. They

do not hesitate to assume the leadership which is rightfully

theirs. The same principle of conduct is true of the lawyers, whose

control in making the laws is proverbial. But the architects seem

to assume an over-modest attitude when planning, zoning, and civic

developments are under way or should be under way.”

Contrary to

this charge, we see in the example of the Washington (D.C.) Chapter

of the AIA that architects of the day were indeed passionate and

involved in community life, even as the country hit its Great

Depression nadir in 1932. Washington Chapter members, who had been

instrumental in convincing the Institute to move from New York to

the District of Columbia, were consistent supporters of the 1901

McMillan Commission Plan, and of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts,

established in 1910. That commission had review authority over

government buildings and open space in the core city, but no

oversight over the rest of the city. Working through the office of

the engineer commissioner of the District of Columbia, through

which permits for construction were obtained, the chapter formed,

in July 1922, the “Architects Advisory Council” to review

proposed construction professionally. Applications and plans, which

the commission office required, were sent to the Washington

Chapter’s Advisory Council, whose volunteers met weekly, rated

the applications, and suggested changes or improvements. The

applications were returned to the engineer’s office, which

passed the council recommendations to the applicant as official

city findings. The council met in architect Horace Peaslee’s

office, but in time seemed more and more an official government

body.

Contrary to

this charge, we see in the example of the Washington (D.C.) Chapter

of the AIA that architects of the day were indeed passionate and

involved in community life, even as the country hit its Great

Depression nadir in 1932. Washington Chapter members, who had been

instrumental in convincing the Institute to move from New York to

the District of Columbia, were consistent supporters of the 1901

McMillan Commission Plan, and of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts,

established in 1910. That commission had review authority over

government buildings and open space in the core city, but no

oversight over the rest of the city. Working through the office of

the engineer commissioner of the District of Columbia, through

which permits for construction were obtained, the chapter formed,

in July 1922, the “Architects Advisory Council” to review

proposed construction professionally. Applications and plans, which

the commission office required, were sent to the Washington

Chapter’s Advisory Council, whose volunteers met weekly, rated

the applications, and suggested changes or improvements. The

applications were returned to the engineer’s office, which

passed the council recommendations to the applicant as official

city findings. The council met in architect Horace Peaslee’s

office, but in time seemed more and more an official government

body.

A 1932 form letter addressed “To Architects, Designers, Home

Builders, Promoters and Civic Associations,” noted “The

Architects Advisory Council, which is now entering upon its tenth

consecutive year of service to Washington, needs no introduction;

but deserves a word of commendation ... This work is made possible

by the freely given service of the representative architects of the

city. Each week a jury of three architects under an able chairman

examines the current plans filed for building permits, and

classifies them as ‘approved,’ ‘average,’ or

‘disapproved.’ In each case, suggestions are made for

improvements, and opportunity is given for reclassification.”

The letter, signed by the assistant engineer commissioner for the

District, noted that the council meets “every Thursday at two

P.M., in the Zoning Office, Room 2, ground floor of the District

Building.”

During its more than a decade of work, thousands of building plans

were considered by the council and construction in the

nation’s capital was measurably improved by its findings. It

is possible that chapters performed the same service in other

cities, but no study of the Architects Advisory Council, or any

similar body, has been located. The records of the Washington group

provide a sound base for any number of theses or dissertations in

city planning, design review, architectural history, and similar

subjects. These records show clearly that Washington architects

were involved in civic development.

The Institute also sponsored architectural studies by chapters and

students. In 1929, these included design of a “Washington

Airport,” by a graduate student of the Yale School of Fine

Arts, and a study of the development of the “north side of

Pennsylvania Avenue,” by a special committee of the Chicago

Chapter and students of the Lake Forest Foundation of Architecture

and Landscape Architecture. Parkway development and the control of

billboards were the subject of other studies.

Historic

celebrations of architectural history

Historic

celebrations of architectural history

As the construction industry came to a screeching halt after

1929, people turned their attention to the existing building stock

and its historic value. In 1930, Library of Congress employee

Leicester B. Holland, FAIA, established the Library’s

“Pictorial Archive of Early American Architecture” to

collect photographs, negatives, and books on American architecture,

an initial effort at the Library to document American architecture.

As 1932 chair of the AIA Committee on the Preservation of Historic

Buildings, Holland reported the establishment of a special zoning

and planning district in Charleston, S.C., called “The Old and

Historic Charleston district, within which building permits are not

to be issued until plans have been approved by a board of

architectural review to prevent developments obviously out of

place. Similar zoning regulations,” he continued, “are in

effect in New Orleans. It is pointed out that while such

regulations afford protection from disfigurement they cannot

prevent demolition.” Designated historic districts such as

these first two, developed with the assistance of architects, with

review boards that require architects as members, are today the

major means of design review in older American communities.

No program that came out of the Depression brought as much work to

architects, drafters, and architecture students, however, as did

the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), patterned after

similar work by the Royal Institute of British Architects and

adapted to American use by AIA member Charles E. Peterson. In late

1933, he sought the advice of the AIA in forming a suitable program

for professionally recording historic buildings for permanent

retention in the collections of the Library of Congress. “On

November 13, 1933, a memorandum proposing the relief employment

under the Civil Works Administration of a substantial number of the

architectural profession in a program recording interesting and

significant specimens of American architecture’ was submitted

to the National Park Service.” The plan proposed the

employment of 1,200 persons, of whom nearly 1,100 were to be

architects, supported by a total expenditure of $448,000.

Within

four days, it had been approved by the secretary of the Interior.

It was then submitted to the Civil Works Administration, and, on

November 29—less than three weeks after it was written,

Peterson reported, the plan was approved in its original form.

“The project was immediately set in motion by ... the National

Park Service,” he wrote, adding: “The proven feasibility

of the whole idea encouraged the National Parks Service, the

American Institute of Architects, and the Library of Congress to

effect, on July 23, 1934, an agreement to carry on the work as a

permanent activity.” That tripartite agreement continues, and

HABS is now one of the largest collections in the world of records

of existing buildings.

Within

four days, it had been approved by the secretary of the Interior.

It was then submitted to the Civil Works Administration, and, on

November 29—less than three weeks after it was written,

Peterson reported, the plan was approved in its original form.

“The project was immediately set in motion by ... the National

Park Service,” he wrote, adding: “The proven feasibility

of the whole idea encouraged the National Parks Service, the

American Institute of Architects, and the Library of Congress to

effect, on July 23, 1934, an agreement to carry on the work as a

permanent activity.” That tripartite agreement continues, and

HABS is now one of the largest collections in the world of records

of existing buildings.

Other activities for raising money for the relief of out-of-work

architects were less grand. One was the 1933 production and sale of

a Colonial Tea Set by the Women’s Division of the

Architects’ Emergency Committee of New York. Produced by

Lennox in an edition not to exceed 5,000, and made available at

cost to the committee, the china was gold rimmed and contained

drawings of historic American buildings, Independence Hall, Mount

Vernon, Monticello, Westover, and the Santa Barbara Mission among

them. Interest was national, and the merits and beauty of the set,

regardless of the money it may have raised for architectural

relief, make the tea set a poignant reminder of how devastating the

Depression was for architects and a valuable collectible

today.

A French

connection . . . and Swedish

A French

connection . . . and Swedish

Still, there were architects with time on their hands who

had money in their pockets. The French Ecole des Beaux-Arts in

Paris had been a major source of training for many of them, and, in

1931, a group of Ecole graduates decided to repay the school by

design and presentation of a flag pole, which they would deliver.

Kenneth Murchison, who originated the idea, was challenged to take

“fifty . . . Beaux-Arts boys, lodge them, bring them back,

include the expense of the flagpole, arrange for a little light

drinking, all for the ridiculous sum of Three Hundred Dollars! And

he did,” Henry Saylor wrote, “believe it or not!” A

steamer was chartered, renamed “American Architect,” and

53 Beaux-Arts alumni left New York on May 21, 1931, bound for

France. They would reboard to return to the U.S. on June 13th.

Between those days they sailed to Europe, toured France where they

were welcomed with parades and parties, and erected and dedicated

the flagpole. “It was a big success. Thousands of students,

the most distinguished French officials, movietone men, enthusiasm

beyond bounds.”

On the return trip, they were unable, despite parties and special

events, to use all the supplies they had brought on board; supplies

they could not bring into the U.S. where prohibition was public

policy. On the last day of the voyage a “burial ceremony

without parallel was held. And when the ‘remains,’

interred in fifteen wooden boxes, were slipped overboard, strong

men broke down and wept and the captain repaired to his stateroom

and cried bitterly.” The story of that voyage, published in an

edition of 100 entitled The

Beaux-Arts Boys on the Boulevards or The Invasion of Paris in

1931, is much more than architectural humor, for it

encapsulates the spirit and energy of the era and, perhaps as

important, contains full-page Tony Sarg caricatures of those who

took the voyage.

At least one

era Gold Medal ceremony was memorable. Ragnar Ostberg, of Sweden

was voted the AIA Gold Medal in 1932 but was unable to travel to

America, and the 1933 AIA Convention was cancelled as an austerity

measure. Ostberg was able to come in 1934 and was feted at an AIA

convention banquet and at the White House where President Franklin

Roosevelt and Mrs. Roosevelt received the Ostbergs and the officers

and directors of the Institute in the East Room and posed for

photographs by White House photographers. The actual award ceremony

was in the East Room “in which was gathered the delegates to

the Sixty-sixth Convention, and many representatives of official

Washington . . . President Roosevelt placed the medal in the hands

of Ragnar Ostberg, at the conclusion of an informal address

intimately spoken in terms which showed the sympathetic

understanding which the president has for architecture and the

architect. In fact, he said that were he starting over again he

would seriously consider the profession of architecture as a life

work.”

At least one

era Gold Medal ceremony was memorable. Ragnar Ostberg, of Sweden

was voted the AIA Gold Medal in 1932 but was unable to travel to

America, and the 1933 AIA Convention was cancelled as an austerity

measure. Ostberg was able to come in 1934 and was feted at an AIA

convention banquet and at the White House where President Franklin

Roosevelt and Mrs. Roosevelt received the Ostbergs and the officers

and directors of the Institute in the East Room and posed for

photographs by White House photographers. The actual award ceremony

was in the East Room “in which was gathered the delegates to

the Sixty-sixth Convention, and many representatives of official

Washington . . . President Roosevelt placed the medal in the hands

of Ragnar Ostberg, at the conclusion of an informal address

intimately spoken in terms which showed the sympathetic

understanding which the president has for architecture and the

architect. In fact, he said that were he starting over again he

would seriously consider the profession of architecture as a life

work.”

The decade ended in 1936 with an AIA Convention in Colonial

Williamsburg, which, though still in its infancy, was providing

work for hundreds of architects, draftsmen, architectural

historians and craftsmen. President Roosevelt wrote lamenting his

inability to attend, but the profession, on the road to economic

recovery, came to see what they had wrought and gather ideas to

take home. Across America, new gasoline stations, city halls,

schools, banks, dime stores, and houses subsequently incorporated

design elements from Colonial Williamsburg. Important historically

and architecturally, Colonial Williamsburg also succeeded

economically, becoming one of the most popular tourist destinations

of the 20th century.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page

|

AIA150 Rolling History  A Beginning, 1857-1866 A Beginning, 1857-1866 The Second Decade, 1867-1876 The Second Decade, 1867-1876 1877-1886: Westward and Upward 1877-1886: Westward and Upward 1887-1896: A Decade of Outreach, Inclusiveness, and Internationalism 1887-1896: A Decade of Outreach, Inclusiveness, and Internationalism Women and Women Architects in the 1890s Women and Women Architects in the 1890s 1897-1906: The AIA Moves to and Changes Washington 1897-1906: The AIA Moves to and Changes Washington The Institute's Influence on Legislative Policy The Institute's Influence on Legislative Policy At 50, the AIA Conceives the Gold Medal, Receives Roosevelt's Gratitude At 50, the AIA Conceives the Gold Medal, Receives Roosevelt's Gratitude Spinning a Golden Webb Spinning a Golden Webb 1909-1917: The Institute Comes of Age in the Nation's Capital 1909-1917: The Institute Comes of Age in the Nation's Capital 1917-1926: A New Power Structure: World War I, Pageantry, and the Power of the Press 1917-1926: A New Power Structure: World War I, Pageantry, and the Power of the Press 1927-1936: A Decade of Depression and Perseverance 1927-1936: A Decade of Depression and Perseverance The AIA in Its Ninth Decade: 1937-1946 The AIA in Its Ninth Decade: 1937-1946 1947-1956: Wright Recognition, White House Renovation, AIA Closes on 100 1947-1956: Wright Recognition, White House Renovation, AIA Closes on 100 The Tenth Decade: 1957-1966 The Tenth Decade: 1957-1966 1967-1976: New HQ and a New Age Take Center Stage 1967-1976: New HQ and a New Age Take Center Stage A New Home for the AIA in 1973; A Greener Home in 2007 A New Home for the AIA in 1973; A Greener Home in 2007 Diversity and the Profession: Take II Diversity and the Profession: Take II  'The Vietnam Situation Is Hell': The AIA's Internal Struggle over the War in Southeast Asia 'The Vietnam Situation Is Hell': The AIA's Internal Struggle over the War in Southeast Asia 1977-1986: Activism and Capital-A Architecture Are Alive at the AIA 1977-1986: Activism and Capital-A Architecture Are Alive at the AIA 1987-1996 Technology, Diversity, and Expansion 1987-1996 Technology, Diversity, and Expansion |

||

|

||

|

1. AIA President Milton Medary presided over the 60th AIA

Convention in Washington, D.C.

|

||