The Community of Architects moves to educate itself and the public

by Tony P. Wrenn, Hon. AIA

The AIA’s first decade was a heady one, as architects,

first from New York City and then from further afield, came

together to look at their obligations—as architects, to

clients—and then at how they might make the public (and each

other) aware of those obligations. Architects from Washington,

D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, and the Northeast soon joined. The

second decade also brought members from Illinois and Ohio in the

Midwest, and from as far south as South Carolina.

Membership,

which numbered 90 at the end of the first decade in 1866, swelled

to more than 280 by 1876. Considering the high standards

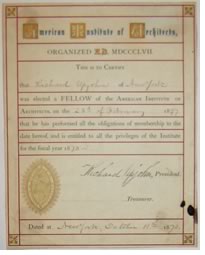

established for membership, such growth is surprising. At a meeting

on June 2, 1868, it was decided that “Fellows of the Institute

shall be such practicing architects as shall upon their nomination

by the Board of Trustees be elected by the existing Fellows.

Candidates may be presented to the Board of Trustees by two

Fellows. The name and residence of every candidate, with

information in regard to his professional education and length of

practice shall be forwarded to the Secretary together with drawings

or photographs and specifications of a proposed or executed

building, accompanied by written statements that the works

represented are the original designs of the candidate . . . Names,

residence, and names of endorsers to be sent to each [current]

Fellow. They vote and return [sealed envelopes] . . . to be opened

before Board . . . Every candidate who receives four fifths of the

votes cast . . . shall be declared elected.” Requirements for

Associate membership were only marginally less demanding.

Membership,

which numbered 90 at the end of the first decade in 1866, swelled

to more than 280 by 1876. Considering the high standards

established for membership, such growth is surprising. At a meeting

on June 2, 1868, it was decided that “Fellows of the Institute

shall be such practicing architects as shall upon their nomination

by the Board of Trustees be elected by the existing Fellows.

Candidates may be presented to the Board of Trustees by two

Fellows. The name and residence of every candidate, with

information in regard to his professional education and length of

practice shall be forwarded to the Secretary together with drawings

or photographs and specifications of a proposed or executed

building, accompanied by written statements that the works

represented are the original designs of the candidate . . . Names,

residence, and names of endorsers to be sent to each [current]

Fellow. They vote and return [sealed envelopes] . . . to be opened

before Board . . . Every candidate who receives four fifths of the

votes cast . . . shall be declared elected.” Requirements for

Associate membership were only marginally less demanding.

Inviting all to join

At the third convention, November 16–17, 1869, in discussing

membership, R. M. Hunt spoke to “prevent the inference being

drawn that we are shutting the doors. On the contrary we have been

to considerable expense, and we do not like to waste money, to

provide circular letters inviting everybody, and we have been

sending them around everywhere. ...” At the fifth convention,

Nov 14–15, 1871, “everywhere” was broadened by a

vote that AIA circulars and publications be sent to all “the

leading newspapers of the country.”

The American Architect and

Building News (AABN) in its October 14, 1876, edition noted

that, “the policy of the Institute is as far as possible from

being exclusive,” and continued: “To the younger

architects especially the Institute should look for support. The

future of the profession is in their hands. Their opportunities of

attainment are better than those of their predecessors; they have

the freshness of interest that belongs to the beginning of a

career. It is of the first importance that it should attract them

to itself by giving them an example and encouragement to attainment

and culture, and by laying before them work which they can attempt

with interest.”

From the

beginning, public relations were carefully managed, with notices of

meetings and actions posted to Crayon, The Architects and Mechanics

Journal, and other publications. The AABN presented a

prospectus to the ninth convention on November 17–19, 1875,

noting that the journal, to be published weekly beginning in 1876,

would be “as general in its professional range as it is

practicable to make it.” AABN solicited information,

correspondence, and essays from the AIA and its members and sought

AIA endorsement. As attractive as the magazine sounded, the

Institute published its own convention proceedings and might, in

the future, publish its own magazine, so the members only agreed to

insure that the magazine got all its mailings. For the rest of the

century, it would be a major source of information on the

AIA.

From the

beginning, public relations were carefully managed, with notices of

meetings and actions posted to Crayon, The Architects and Mechanics

Journal, and other publications. The AABN presented a

prospectus to the ninth convention on November 17–19, 1875,

noting that the journal, to be published weekly beginning in 1876,

would be “as general in its professional range as it is

practicable to make it.” AABN solicited information,

correspondence, and essays from the AIA and its members and sought

AIA endorsement. As attractive as the magazine sounded, the

Institute published its own convention proceedings and might, in

the future, publish its own magazine, so the members only agreed to

insure that the magazine got all its mailings. For the rest of the

century, it would be a major source of information on the

AIA.

Branching out

geographically

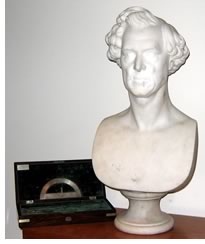

That first formal convention, held in New York on October

22–23, 1867, signaled a second decade for the AIA. AIA

President Upjohn noted in his address to the first convention,

“It is now 10 years since a few architects of this city

convened for the purpose of considering the expediency of forming a

society of members of their profession. It was held as a certainty

that, thus united, architects would assist each other, by friendly

intercourse, in the acquirement of every branch of professional

knowledge necessary for the progress, either of the individual

member, or of the proposed association, and our experience, as a

society, has not disappointed us.”

The first three conventions (1867–69) were in New York City;

the fourth, in 1870, was held in Philadelphia; the fifth in 1871 in

Boston; and the sixth in 1872 in Cincinnati. When, at the 1871

convention, J. D. Hatch of New York City questioned whether there

were enough members in Cincinnati to justify holding a convention

there, P. B. Wight of Chicago was ready with an answer. “There

are eleven Fellows of the Institute in Cincinnati, and there are a

great many Fellows of the Institute quite near to Cincinnati

through Ohio and Illinois within less than a day’s

journey.” The membership no longer resided and practiced just

in New York.

Prior to the first convention in 1867, members celebrated on

February 22, marking both George Washington’s birthday and the

birth of the Institute on Feb. 23. They met at Delmonico’s to

share good food, drink, and fellowship. The conventions begun in

1867 were more formal, held in the fall, with AIA business

discussed, reports of AIA committees received, papers on topics of

general interest to the membership read, and, beginning with the

1876 first convention, Chapter reports.

Local chapters

are formed; national keeps national aspirations

Local chapters

are formed; national keeps national aspirations

It was clear that the small organization, with most of its members

then from New York, had national aspirations, quite different from

local ones. These needed to be addressed and Upjohn reported in his

1867 first convention speech “a radical change . . . effected

in the organization of our society, consisting in the

constitutional provision for chapters in affiliation with the

general and national objects of the Institute, while yet, for local

affairs, under the government of their own.” The New York

Chapter was formally organized, it reported to the 1867 convention,

“on the evening of March 19, 1867, at the Everett

House.”

On March 24, at a subsequent meeting of the Institute, chapters

were legalized through bylaws changes. Regulations adopted required

that chapter membership requirements “not be inconsistent with

those required for Associate membership of the Institute, and that

in other respects . . . regulations . . . not conflict.” The

AIA required that “all communications with Foreign bodies

whether architectural or otherwise” be conducted through the

Institute. Clearly, the international standing of the Institute was

not to be diluted. Its reputation had been recognized that same

year, 1867, when the Royal Institute of British Architects elected

AIA President Upjohn an Honorary and Corresponding Member.

At the 1867 convention, the first chapter, New York, gave an annual

report, and a telegram to the convention from S. E. Loring of

Chicago was read. “We organize chapter tomorrow. I regret my

detention here,” Loring telegraphed. The AIA Secretary

responded “Convention in session. Your telegram just received

and greeted with enthusiasm. God speed your undertaking.

Philadelphia Chapter organized last week and delegates are

present.” The Boston Society of Architects would soon follow,

and agree to become an AIA Chapter, though not to change its name.

By the time the annual convention was held in Cincinnati, in 1872,

the Cincinnati Chapter was already two years old.

Early on, education offers a major

challenge

One pressing question remained: How to adequately educate

architects. Discussion topics during the conventions of the

1870s—chimney construction, fireproofing, terra-cotta,

acoustics, cements and concrete, mansard roofs, apartment

construction, the relations of science and art in architectural

study, elementary training of the architect, Colonial architecture,

the architecture of Washington, D.C.—could only partially

fulfill the Institute’s need to educate, no matter how long

the paper presented or how detailed the discussion. Hobart Upjohn,

a third-generation Upjohn architect, later wrote, “course by

course, the Institute built its program, and, as we study its

progress, we see that in endeavoring to advance the profession and

to interest the public, the real objective was, actually,

education. Education of the members by association, of the

individuals by the preparation, reading and discussion of papers,

and by setting up a common library on architecture; education of

the public by lectures and publicity on the practice of

architecture; and education of students by organizing and giving

courses on architecture in established schools and

colleges.”

Indeed,

education of the architect was among the first ideas discussed by

the membership. On Oct. 20, 1857, Charles Babcock, AIA founder and

son-in-law of Richard Upjohn, had read a paper titled “The

Ways and Means of Accomplishing the Elevation of the

Architect’s Profession.” He suggested “The education

of a thorough architect requires as much time and study, and the

application of as fine powers of mind, as are ever given by any

department of human labor or learning.” The study of

architecture, he argued, should be “esteemed by the side of

divinity, medicine and law.”

Indeed,

education of the architect was among the first ideas discussed by

the membership. On Oct. 20, 1857, Charles Babcock, AIA founder and

son-in-law of Richard Upjohn, had read a paper titled “The

Ways and Means of Accomplishing the Elevation of the

Architect’s Profession.” He suggested “The education

of a thorough architect requires as much time and study, and the

application of as fine powers of mind, as are ever given by any

department of human labor or learning.” The study of

architecture, he argued, should be “esteemed by the side of

divinity, medicine and law.”

AIA committees studied the topic and discussions continued

regularly during the decade. In 1865 William Robert Ware, who

joined the AIA in 1859 and was advanced to Fellow in 1861,

apparently the first such advancement, according to available

archival documents, was appointed as a professor at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to teach architecture. Ware

took a year off to study architecture education abroad and, in

1868, opened a school of architecture at MIT, making it the first

American college to offer an architecture degree. Charles Babcock,

the AIA founder who spoke so fervently of architectural education

in 1857, developed a program at Cornell in 1871, while N. Clifford

Ricker began a program at the University of Illinois in 1873.

Ricker did not become an AIA member until 1879, but all three men

worked closely with the AIA and its members in advancing

architecture education.

Though conventions, publications, chapters, and schools of

architecture are signal accomplishments for any decade, there was

more. Fees for architects were codified during that second decade,

but competitions regulation proved a difficult and thorny issue for

architects. Holding a competition was a popular way to choose

building designs. Yet architects were seldom asked to serve on

building committees that chose competition winners, were not paid

for their drawings, and had no assurance that they would have any

say in construction, even if their plans were chosen.

At the fifth convention, in Boston in 1871, in discussing

competitions, S. J. Thayer, an 1870 Associate member and 1871

Fellow, asked approval of a resolution “that it shall be

considered unprofessional for any member of the Institute to allow

himself to be employed in cases where he is superseded in authority

in the execution of his work.” Though some felt the resolution

presented an insurmountable problem, Upjohn was not among them.

“The architect is the master builder,” he said.

“That settles it. I have always carried it out so, through the

whole course of my professional life. I never would submit to any

man, or allow any person to come on the premises and dictate to me

. . .” Hunt agreed. “I will [not] make a design for any

client without the distinct understanding and always in writing

kept in a copy book, that . . . if it is to be carried out, I am

the only man to carry it out.” Thayer’s resolution

carried.

Vigilance for

the public good

Vigilance for

the public good

It surprises in reading the records of the Institute to learn how

prescient members were 140 years ago. In discussing competitions

for the New York Post Office on December 1, 1867, Upjohn opened

with “an earnest protest [not against competitions but]

against the proposed site. He thought that the commission had

already gone too far, for in his opinion the site designated for

the Post Office was not well selected, and no building designed for

that ground, the southern end of the Park [City Hall Park] would be

fitting. . . . He insisted most emphatically upon the fact that

that ground should never be closed, but be forever kept open, for

if a building were erected there then the whole park would soon be

built upon.” In a February 9, 1867, interview published in the

Tribune, he spoke publicly

against the site, saying it “was not only of vital importance

to the city as an open breathing-space, but it was of equal value

on artistic grounds.” He insisted that the whole of City Hall

Park “should be liberally adorned and forever kept

open.”

At the end of the second decade, in 1876, the membership elected

Thomas U. Walter, an AIA founder and the architect who had given

the country a symbol of stability through the design and completion

of the U.S. Capitol dome during the Civil War, to lead the

Institute into its third decade. It could hardly have chosen, as

its second president, a better successor to Upjohn.

The second decade brought approval of documents concerning fees and

competitions; the first 10 conventions, each with published

proceedings; the authorization and establishment of chapters; the

establishment of schools of architecture; and the advance of

membership from the Northeast to the Midwest and South. Not many

20-year-old organizations have so influenced American life and

culture.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page

|

AIA150 Rolling History  A Beginning, 1857-1866 A Beginning, 1857-1866 The Second Decade, 1867-1876 The Second Decade, 1867-1876 1877-1886: Westward and Upward 1877-1886: Westward and Upward 1887-1896: A Decade of Outreach, Inclusiveness, and Internationalism 1887-1896: A Decade of Outreach, Inclusiveness, and Internationalism Women and Women Architects in the 1890s Women and Women Architects in the 1890s 1897-1906: The AIA Moves to and Changes Washington 1897-1906: The AIA Moves to and Changes Washington The Institute's Influence on Legislative Policy The Institute's Influence on Legislative Policy At 50, the AIA Conceives the Gold Medal, Receives Roosevelt's Gratitude At 50, the AIA Conceives the Gold Medal, Receives Roosevelt's Gratitude Spinning a Golden Webb Spinning a Golden Webb 1909-1917: The Institute Comes of Age in the Nation's Capital 1909-1917: The Institute Comes of Age in the Nation's Capital 1917-1926: A New Power Structure: World War I, Pageantry, and the Power of the Press 1917-1926: A New Power Structure: World War I, Pageantry, and the Power of the Press 1927-1936: A Decade of Depression and Perseverance 1927-1936: A Decade of Depression and Perseverance The AIA in Its Ninth Decade: 1937-1946 The AIA in Its Ninth Decade: 1937-1946 1947-1956: Wright Recognition, White House Renovation, AIA Closes on 100 1947-1956: Wright Recognition, White House Renovation, AIA Closes on 100 The Tenth Decade: 1957-1966 The Tenth Decade: 1957-1966 1967-1976: New HQ and a New Age Take Center Stage 1967-1976: New HQ and a New Age Take Center Stage A New Home for the AIA in 1973; A Greener Home in 2007 A New Home for the AIA in 1973; A Greener Home in 2007 Diversity and the Profession: Take II Diversity and the Profession: Take II  'The Vietnam Situation Is Hell': The AIA's Internal Struggle over the War in Southeast Asia 'The Vietnam Situation Is Hell': The AIA's Internal Struggle over the War in Southeast Asia 1977-1986: Activism and Capital-A Architecture Are Alive at the AIA 1977-1986: Activism and Capital-A Architecture Are Alive at the AIA 1987-1996 Technology, Diversity, and Expansion 1987-1996 Technology, Diversity, and Expansion |

|||

|

|||

|

Tony Wrenn, Hon. AIA,

who retired as the AIA’s archivist in 1998 after 18 years of

service, is now a researcher/writer based in Danville,

Va.

|

|||