Octagon acquired, publications begun, friends in the White House established

by Tony P. Wrenn, Hon. AIA

The 1896

AIA Convention decided that it was finally time to answer the

question of where the permanent headquarters of the Institute

should be, and delegates chose Washington, D.C. The U.S. government

was the largest single builder in America, and Washington was where

legislators who controlled federal funding sat. It was also the

headquarters city for many other national organizations with which

architects shared common interests. Whether the AIA should partner

with an organization, such as the Smithsonian, or establish

independent headquarters was still to be decided.

The 1896

AIA Convention decided that it was finally time to answer the

question of where the permanent headquarters of the Institute

should be, and delegates chose Washington, D.C. The U.S. government

was the largest single builder in America, and Washington was where

legislators who controlled federal funding sat. It was also the

headquarters city for many other national organizations with which

architects shared common interests. Whether the AIA should partner

with an organization, such as the Smithsonian, or establish

independent headquarters was still to be decided.

At the 31st AIA Convention, in Detroit in 1897, AIA President

George B. Post noted in his annual address:

The last Convention of the

Institute wisely resolved that its head-quarters should be removed

to Washington ... it is my opinion that it is important that the

change should be made as soon as it can be conveniently

accomplished ... Establishing the Home of the Institute in the

National Capital will form an era in its existence. It has passed

fairly through its formative stage—its period of organization.

From struggling youth it has grown to vigorous manhood and has

become a power in the community. The time has come when it is

possible that it should undertake work better and more important

that [sic] the perfection of its interior organization and

establishing provisions for the regulation of professional

practice.

Post suggested the election of a paid secretary, the

reestablishment of Associate membership, to which all members would

be elected, with Fellowship as a higher category to which members

could be advanced. Licensing of architects by the states was

supported along with an increased emphasis on architectural

education and the establishment of scholarships. “It is the

proud claim of the architect that his work forms the most positive

and enduring evidence of civilization. In all countries and periods

the government has been the great builder and appointment to

government work has ever been the supreme reward of proved ability

in our profession ... No movement for the advancement of art in our

country has occurred in which the individual members of this body

have not exerted a controlling influence” Post concluded,

asserting an AIA future of even greater control and

influence.

Licensing, which had been debated since the 1880s, was still a hot

topic in 1897. The Board of Directors, in its Annual Report took no

direct stand, but urged upon the Institute:

the importance of an educational

test for membership ... and a full realization of the fact that the

conduct of every member should be guided by the highest

professional ethics rather than by commercial and hustling

competition with the concomitants attending the scramble for

business which marks the spirit of the age, and which unfortunately

has found some foothold among architectural practitioners, some of

whom may be able to write F.A.I.A. after their names.

Within the year, 1897, Illinois became the first state to adopt an

architectural licensing law, a process that would not be completed

until 1955 when Vermont adopted its licensing law.

On

to Washington

On

to Washington

When the Washington Chapter first presented a resolution urging a

move to Washington, in 1889, it suggested the Octagon as AIA

headquarters. A Federal Style mansion, designed by Dr. William

Thornton, who had won the competition for design of the U. S.

Capitol, it was again suggested to the Convention in 1897. Glenn

Brown, of the Washington Chapter, had proven the integrity of the

Capitol in his study of the building’s design, which led, in

1900 to the publication of Volume 1 and in 1903 to Volume 2 of his

History of the United

States Capitol, still a basic document on the

building and an early publication on public history, which, in

turn, established Brown as a prominent national historian.

Though the Institute frequently called the house “Octagon

House,” it had always been referred to by its builders as

“The Octagon.” It was known by that name locally, and

that is its official name. Considered one of the most important

buildings in Washington, it was second only to the White House as a

Washington residence. Indeed, after the White House was burned

during the War of 1812, The Octagon served as the residence of

President James and First Lady Dolley Madison. It was there in 1815

that Madison signed the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of

1812. The house had been built for Virginia planter John Tayloe and

his family and served as a Tayloe residence in Washington until

just before the Civil War. It later served as a school, as a

Hydographic Office for the Navy, and, having fallen on hard times

late in the 19th century, was in ill repair and housed a

caretaker.

The Board of Directors voted late in 1897 to lease The Octagon, and

undertook repairs with a view to receiving AIA members there at the

1899 Convention, which would be held in Washington in November.

That reception, and indeed the convention, indicated just how much

change, for the organization and its members, the move to

Washington presaged. The White House indicated on November 1 that

the president would receive members “this Tuesday afternoon at

2:30,” and “...promptly at 2 o’clock the members,

with their wives and lady friends, went in a body to the White

House and were received in the East room, each member being

introduced by the Secretary of the Institute [Brown] to President

McKinley, by whom they were cordially greeted,” according to

the convention minutes.

From the White House the entire

body went to the Treasury Department to pay their respects to Hon.

Lyman J. Gage, the Secretary of the Treasury [in whose office

architects under the Supervising Architect designed and oversaw

construction of government buildings] ... Each person was

introduced by the Secretary of the Institute to Secretary Gage and

after a brief informal interview the members and friends went to

the “Octagon House” at the junction of New York Avenue

and 18th Street, the new Headquarters of the Institute.

The building was thoroughly inspected from top to bottom with much

interest and the work of the Committee having charge of the fitting

up and restoring of the house was highly commended and fully

appreciated by all present, especially by those who had seen it

when it was used as a store house for old rags and junk. The house

has...been restored as nearly as possible to its original condition

even to the tints on the walls of several rooms which were in most

of the rooms buried beneath coats of paper or whitewash. Many of

the original drawings of the Capitol, which had been found at the

Capitol after diligent research by Mr. Glenn Brown, were displayed

in one of the rooms and studies of the Washington Architectural

Sketch Club were hung in another

room.

The brush

with celebrities was not over. Before the 1898 Convention

adjourned, “members and their wives and friends took the

trolley cars for Cabin John Bridge where a bountiful lunch was

served and the afternoon was spent in social intercourse and in the

enjoyment of the beautiful natural scenery. Upon the return trip a

stop was made at Glen Echo and some of the party were able to call

upon and pay their respects to Miss Clara Barton, whose home and

depot of supplies is at Glen Echo.”

The brush

with celebrities was not over. Before the 1898 Convention

adjourned, “members and their wives and friends took the

trolley cars for Cabin John Bridge where a bountiful lunch was

served and the afternoon was spent in social intercourse and in the

enjoyment of the beautiful natural scenery. Upon the return trip a

stop was made at Glen Echo and some of the party were able to call

upon and pay their respects to Miss Clara Barton, whose home and

depot of supplies is at Glen Echo.”

Change is in the air

Far-reaching change resulted from adoption of a new

Constitution and By-Laws at the 1898 convention. Associate and

Fellow were reestablished as membership categories, delegates in

proportion to membership in chapters would control future

conventions, and the duties of Secretary and Treasurer were

combined, and the office invested with broad powers, effectively

making the Secretary the chief operating officer, the chief

financial officer, and the chief executive officer. Glenn Brown, of

the Washington Chapter, was elected to the position. There could

hardly have been a better choice.

Two months after the 1898 Convention, the AIA officially

inaugurated The Octagon as its headquarters when the Board of

Directors met there on January 1, 1899. In 1902, after some four

years of leasing, the Institute purchased The Octagon.

Henry Van Brunt was elected president for 1899, when the convention

met in Pittsburgh. It was the first convention to which delegates

had been elected by the chapters, which, Brown later wrote,

“proved the wisdom of the measure, as the Chapters had elected

their most prominent men for this service.” There was another

change too, for “at this Convention ... papers were read on

topics relating to the Fine Arts, emphasizing this side of

Architecture, as with few exceptions papers before this date had

been on methods of practice or construction.” Though the

business of architecture continued to be discussed at conventions

and chapter meeting, architecture as an art would be a dominant

concern of the AIA for the next decade and more.

Architecture as art

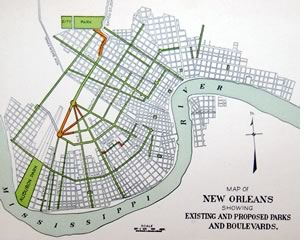

The Washington Chapter had, in 1895, been instrumental in

organizing the Public Art League with a national membership and

nationally known leaders—Richard Gilder, editor of Century Magazine was elected

president; Charles McKim, first vice president; Augustus

Saint-Gaudens, second vice-president; Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and

Daniel Burnham, directors; and Brown, corresponding secretary.

Brown wrote in his autobiography Memories that “We found

appeals to Congress by our small local body accomplished nothing.

The way to the legislator’s brain was through marked interest

from their home voters.”

The

organization lobbied for a national fine arts commission and for

acquisition of land along Rock Creek as a public park. The Corps of

Engineers “decided that Rock Creek Valley should be filled,

making a level plain of made ground between Washington and

Georgetown, in some places thirty feet deep. It was their intention

to carry Rock Creek to the Potomac through a huge culvert ... Rock

Creek as it runs through the valley is an unusually picturesque

stream, in many spots charmingly attractive. It is the natural

outlet from the upper country to the Potomac River. Why replace it

with a large area of unstable made ground? After a battle of

several years...” Rock Creek was set aside in 1900 by Congress

for the “benefit and enjoyment of the people of the United

States,” the first in a long line of successes for the

Washington Chapter, the Public Art League, and their AIA and

public-art allies.

The

organization lobbied for a national fine arts commission and for

acquisition of land along Rock Creek as a public park. The Corps of

Engineers “decided that Rock Creek Valley should be filled,

making a level plain of made ground between Washington and

Georgetown, in some places thirty feet deep. It was their intention

to carry Rock Creek to the Potomac through a huge culvert ... Rock

Creek as it runs through the valley is an unusually picturesque

stream, in many spots charmingly attractive. It is the natural

outlet from the upper country to the Potomac River. Why replace it

with a large area of unstable made ground? After a battle of

several years...” Rock Creek was set aside in 1900 by Congress

for the “benefit and enjoyment of the people of the United

States,” the first in a long line of successes for the

Washington Chapter, the Public Art League, and their AIA and

public-art allies.

After 1899, the Public Art League joined The Washington Chapter of

the AIA, Washington Architectural Club, Archaeological Society of

America, American Federation of Arts, American Academy in Rome,

Washington Society of Fine Arts, and the National Society of Fine

Arts as tenants in The Octagon. Together, they provided a

nationwide source of influential members and leaders who joined the

AIA in campaigning for the return of Washington to the concepts

laid down by Pierre Charles L’Enfant in his original plan for

the city.

The word in print

One far-reaching act of the 1899 Convention was authorization of a

“quarterly bulletin, giving an index to the periodicals and

society literature that is received in the way of exchange; and in

the same bulletin to give titles, size, and contents, with short

review of current books on architecture and the allied arts

...” The first issue of The

American Institute of Architects Quarterly

Bulletin appeared in April 1900. For the next

12 years, it would appear four times yearly, and become one of the

most important and respected serial publications on architecture

and the City Beautiful movement. As the forerunner of the AIA Journal and publications of

the AIA Press, it set high standards.

1900 marked the centennial of the move of the U.S. capital from

Philadelphia to Washington, and the AIA met in Washington that year

intent on reinstating L’Enfant’s plan as a working

document for development and seizing control of development of the

White House from the Corps of Engineers. All the elements necessary

to put both plans into effect were present. AIA Secretary Brown was

well known to the McKinley White House. He had designed the

reviewing stand for a McKinley inaugural and upgraded sanitation

and plumbing at the White House. He had easy access to the White

House and often, when showing important visitors or members around

Washington, ended with a tour of the White House, entering

“through the basement, then through the principal floor ...

ending up by taking them out on the south portico and calling their

attention to the beauty of the grounds and to the charming view of

the Potomac.”

Brown had

written about “The Selection of Sites for Federal

Building” in Architectural

Review in 1894, and the subject remained one he seems to

have talked of constantly. In the 1894 article he wrote glowingly

of L’Enfant’s siting of the White House and the Capitol.

The Capitol Dome, he wrote, “is constantly peeping out through

the trees down the valleys in the most unexpected places as one

drives or wanders through the country.” Architects, artists,

sculptors, and landscape architects could, he believed, revitalize

the L’Enfant plan and “give the country a parked avenue

in Washington unequaled by anything in the world—a triumph of

the arts.”

Brown had

written about “The Selection of Sites for Federal

Building” in Architectural

Review in 1894, and the subject remained one he seems to

have talked of constantly. In the 1894 article he wrote glowingly

of L’Enfant’s siting of the White House and the Capitol.

The Capitol Dome, he wrote, “is constantly peeping out through

the trees down the valleys in the most unexpected places as one

drives or wanders through the country.” Architects, artists,

sculptors, and landscape architects could, he believed, revitalize

the L’Enfant plan and “give the country a parked avenue

in Washington unequaled by anything in the world—a triumph of

the arts.”

Architects, not engineers

Planning for the 1900 Convention in Washington, which the

AIA would tag on to the end of the Centennial move celebration,

which was planned for December 12, took almost a year as Brown and

convention planners meticulously crafted a session “On the

General Subject of the Grouping of Government Buildings, Landscape,

and Statuary in the City of Washington.” Nationally known

leaders and speakers—C. Howard Walker, Edgar V. Seeler,

Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., and H. K. Bush Brown—presented

papers, and both the public and press were well represented,

especially since the evening of papers followed the day after a

White House reception where the Corps of Engineers presented its

plans for enlarging the White House. Those plans envisioned massive

structures on either side of the White House which were compatible

in neither design nor scale, and the AIA, in prepared petitions

from some 40 organizations and AIA chapters from around the nation

and in interviews, critiqued the plan to the press and to

Congressional committees, suggesting strongly that White House

restoration be put in the hands of architects, not engineers, and

noting the Convention session the following night on the

subject.

In the discussion on the White House, the planning concepts that

would be so important in developing Lafayette Square across from

the White House 160 years later were clearly set forth:

... the present building [White

House] is a pleasing example in architecture, dignified in its

surroundings with trees that it would require a century to replace;

that, inasmuch as the building typified the best architecture of

the beginning of the nation, and embodies its traditions to the

present time, and as its successor should so typify the best of

to-day and would so be held in the future, for which the present

architects would be considered responsible, we ask that before any

alterations or additions are undertaken Congress will call to its

aid an architect (trained in such problems) whose life work has

been of such character that his advice, if heeded, will give

assurance that such alterations or additions will neither mar the

present beauties nor fail to obtain satisfactory results from the

works undertaken.

To

underscore the AIA position, the convention adopted a resolution

stating “the White House is one of the best examples of early

American architectural art; and, Inasmuch as it is especially

endeared to the people as the residence of all the Presidents of

the Republic since General Washington; and inasmuch as its

accommodations are no longer adequate as the residence and office

of the Chief Magistrate, That, therefore, a commission largely

formed of architects of recognized ability should be appointed,

without delay.”

To

underscore the AIA position, the convention adopted a resolution

stating “the White House is one of the best examples of early

American architectural art; and, Inasmuch as it is especially

endeared to the people as the residence of all the Presidents of

the Republic since General Washington; and inasmuch as its

accommodations are no longer adequate as the residence and office

of the Chief Magistrate, That, therefore, a commission largely

formed of architects of recognized ability should be appointed,

without delay.”

After discussion and committee reports on the matter, the

resolution voted in noted:

Whereas it is evident that the

location and grouping of public buildings, the ordering of

landscape and statuary, and the extension of the park system in the

District of Columbia are matters of national concern, and should be

made in accordance with a comprehensive artistic scheme; and

Whereas the execution of each single structure or public

improvement outside such a scheme would be an impediment to the

artistic development of the District; Resolved, That the American

Institute of Architects advocates and urges upon Congress the

importance of procuring, through a commission created for this end,

the best obtainable general design for the purpose aforesaid.

Such a commission would be a logical outgrowth of the AIA panel on

“Grouping of Government Buildings.” All panelists had

exchanged papers, all had toured, with Brown and others, the Mall

and adjacent areas which they would discuss. All had been provided

with maps and printed material. Brown and Washington Chapter member

Joseph Hornblower traveled to Paris in September 1900 and collected

lantern slides to be used by the panelists, all of whom had visited

the major cities of Europe and collected their own graphics. The

December 13 presentation seems to have been both graphically and

oratorically riveting.

Senator McMillan gets on board

The suggested committees were appointed, one to communicate

the AIA resolution on the White House to the president, and the

other to communicate the desire for a Federal Commission on

Grouping to the Congress. Charles Moore, friend and fellow Cosmos

Club member of Glenn Brown and aide to Senator James McMillan of

Michigan, who headed the Senate District Committee, had often

talked with Brown and others about the L’Enfant Plan and the

desirability of revitalizing it. The AIA committees talked with

Moore and on December 19, less than a week after the panel

presented its papers at the convention, Sen. McMillan introduced a

resolution in the Senate to print the AIA papers as a Senate

Document. The Journal of

Proceedings reported “These papers, together with the

discussion of the subject, prepared by Cass Gilbert, Paul J. Pelz,

and George O. Totten Jr., will be published as a Senate Document

for the use of Congress, and known as Senate Document No. 94, 56th

Congress, 2d Session.” Moore in an introduction wrote

“The report of the Centennial Celebration [of the move of the

capital from Philadelphia to Washington] now at press, will show

the ideas of the laity; this publication contains the tentative

plans of the experts.”

The Senate document was sent to all AIA members, some 40 American

societies associated with the Public Art League, 43 foreign

societies, and 59 architecture and allied arts periodicals. Of even

greater importance, the papers and their ideas were in print and

available to politicians at all levels, in an official government

document.

Brown, AIA President Robert S. Peabody, Moore, Sen. McMillan, and

members of the Senate District Committee met immediately and

developed Senate Resolution 139 introduced in the Senate December

17, 1900, authorizing the appointment of a “commission, to

consist of two architects and one landscape architect eminent in

their profession, who shall consider the subject of the location

and grouping of public buildings and monuments to be erected in the

District of Columbia and the development and improvement of the

entire park system of said District, and shall report to Congress

thereon.”

From an AIA list, McKim, Burnham, and Olmsted were appointed to the

McMillan or Park Commission; August Saint Gaudens was later added.

All were members or honorary members of the AIA, and well known

nationally and internationally. Their report would, in time, clear

the Mall of intrusions, relate the Capitol to a Union Station to be

built to its northeast, establish a monument to Grant at the

Capitol end of the Mall, one to Lincoln at the Potomac River end,

and group government buildings in the Federal Triangle area to the

north of the Mall and along Independence Avenue to the south of the

Mall. The models, plans, maps, and delineations that accompanied

the published report in 1901 established a master plan for

development in the nation’s capital that would channel

development almost to the present.

Professional

cooperation and public service

Professional

cooperation and public service

Members assembled in Buffalo, in October 1901, on the

grounds of the Pan-American Exposition. Earlier, President McKinley

had been assassinated there, and the AIA mourned the loss of a

friend. AIA President Peabody also mourned the loss of the small

office and the individual architect solely responsible for his

designs:

As in business, trade has massed

itself into great consolidation and combinations, so commercialism

has brought new problems to our art. It is a surprising fact that

in democratic America, of all places, a country where individual

exertion and independent action is the mainspring of public life,

the spirit of co-operation and combination has so largely

supplanted in our art the production of the individual. It is,

perhaps, a thing to deplore that an architect’s office should

resemble a department store or should be open to the derisive

charge of being a plan factory.

Brown noted the 1902 Convention as being a notable one in which

“the members of the Park Commission explained the report on

the Park improvement of Washington, and the Octagon House became

the property of the American Institute of Architects through the

initiation of Mr. Chas. F. McKim, the President.” The Journal of Proceedings

reproduced both text and graphics from the Park Commission Plan and

McKim told members, “I can give the Institute no better wish

than that as time shall fill the building [The Octagon] with

memories and associations of our own work and achievement, it may

become indeed a home to the architects of this land, and that it

may typify to those who assemble in it, and to the citizens of

Washington as well, the spirit of public service.”

That spirit of public service was notable in the friendship

developing between architects and President Theodore Roosevelt, who

oversaw the restoration and enlargement of the White House in 1902.

Architect for the work was AIA President McKim, while the

supervising architect was AIA Secretary Glenn Brown. The success of

that work and the developing friendship between Roosevelt and the

AIA would have far-reaching results in the next few years, results

that may never again be matched.

No

little plans continue

No

little plans continue

The 1901 Park Commission Plan continued to be discussed at the

Cleveland Convention in 1903 when Sir Aston Webb, president of the

Royal Institute of British Architects, cabled AIA President McKim:

“Washington Commission Park improvement plans as fine as

anything could be.” The Government Printing Office printed

Park Improvement Papers in

1903, “A series of twenty papers relating to the improvement

of the park system of the District of Columbia, printed for the use

of the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia; edited and

compiled by Charles Moore, the Clerk of that Committee.” Among

the papers were Glenn Brown’s “The Making of a Plan for

Washington City,” a paper he had read before the Columbia

Historical Society on January 6, 1902. The AIA had produced lantern

slide shows, which were sent around the country and provided

speakers on request in support of the implementation of the Park

Commission Plan, efforts which continued for the next several

years.

For several years, numbering for the

conventions is confusing. The 1904 Convention, for example was

“held in the Octagon, December 15, 1904, and at the Arlington

Hotel, Washington, D.C. on January 11, 12 and 13th 1905.” The

Board met at The Octagon, called the Convention, and, no quorum

being present, recessed until 1905. Brown wrote “At the 1904

Convention [actually in January 1905] held in Washington, the

Institute gave its first formal annual dinner. This dinner was

attended by the most distinguished men in the United States. The

President of the United States, and members of his Cabinet,

Senators and Representatives, the Cardinal, the Bishop of

Washington, Presidents of Universities, Art Museums and Societies,

men eminent in Art, Science and Literature, were present at this

dinner. On this occasion was inaugurated the effort to secure a

permanent endowment of one million dollars for the American Academy

in Rome.” Within a year, some $800,000 had been raised.

Charles Moore described the room: “Under the direction of Mr.

Frank D. Millet, the dining-room was effectively decorated in

white, with branches of palms held together by fastenings bearing

the names of the Chapters. Festoons of green emphasized the

architectural lines of the room. Behind the President’s chair

was the great seal of the Institute; while at the western end of

the room the cipher of the Institute was flanked by the colors of

the States of the Union, arranged as trophies. The high table

extended along three sides of the room. Near the entrance a box was

arranged for Mrs. Roosevelt and her guests.”

The

President, in his address said,

The

President, in his address said,

There are things in a

nation’s life more important than beauty; but beauty is very

important. And in this nation of ours, while there is very much in

which we have succeeded marvelously, I do not think that if we look

dispassionately at what we have done, we will say that beauty has

been exactly the strong point of the nation! It rests largely with

gatherings such as this, and with the note that is set by men such

as those I am addressing tonight, to determine whether or not this

shall be true of the future.

He discussed government building, continuing,

I would say that the best thing

that any elective legislative body can do in these matters is to

surrender itself within reasonable limits to the guidance of those

who really do know what they are talking about ...

The only way in which we can hope to have worthy artistic work done

for the Nation, State or municipality is by having such a growth of

popular sentiment as will render it incumbent upon successive

administrations, or successive legislative bodies, to carry out

steadily a plan chosen for them, worked out for them by such a body

of men as that gathered here this evening ...

... beginning has been made and now I most earnestly hope that in

the national capital a better beginning will be made than anywhere

else; and that can be made only by utilizing to the fullest degree

the thought and the disinterested efforts of the architects, the

artists, the men of art, who stand foremost in their professions

here in the United States, and who ask no other reward save the

reward of feeling that they have done their full part to make as

beautiful as it should be the capital city of the Great

Republic.

The banquet papers, published under the title The Promise of American

Architecture, are

worth reading still.

On December 29, 1906, the 40th annual convention of The American

Institute of Architects was called to order in The Octagon. There

being no quorum “the Convention took a recess until January 7,

1907,” with “Celebration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of

its Foundation” planned for that day.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page