by Tony P. Wrenn, Hon. AIA

It came as no surprise to architects that with the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson as president on March 4, 1913, ready access to the power of the presidency ended for architects. Wilson’s opponents, President William Howard Taft and former President Theodore Roosevelt, whom the Republican Party split to nominate, were respected friends of architecture and the arts. Both also were AIA members: Taft was elected Hon. AIA in 1907, Roosevelt in 1909. Clearly, they had had the support of the art community, and Scotch Presbyterian Wilson was in no mood to forgive architects for their lack of support for him.

Wilson’s first wife, Ellen Axson, an artist, involved herself in the plight of the alley dwellers of Washington, seeking decent housing and other help. The AIA allied itself with her cause, and she attended at least one AIA convention before her death after a short illness, on August 6, 1914. The second Mrs. Wilson was Washington socialite Edith Bolling Galt, whom Wilson married in December 1915. Her interests did not include the arts or welfare work, and the deepening war in Europe increasingly required her husband’s time. There was subsequent access to the White House, but never again would there be relationships to equal those of the AIA and presidents McKinley, Roosevelt, and Taft.

With the

election of Warren Harding in 1920, Herbert Hoover became Secretary

of Commerce and worked closely with the AIA in problems of housing,

appointed architects to Commerce committees, endorsed AIA programs

such as the Architects Small House Service Bureau, and addressed

the AIA Convention in 1921. He worked closely enough with the

Institute to earn him an Hon. AIA in 1922.

With the

election of Warren Harding in 1920, Herbert Hoover became Secretary

of Commerce and worked closely with the AIA in problems of housing,

appointed architects to Commerce committees, endorsed AIA programs

such as the Architects Small House Service Bureau, and addressed

the AIA Convention in 1921. He worked closely enough with the

Institute to earn him an Hon. AIA in 1922.

President Harding spoke at the AIA Convention in Washington in 1923 in ceremonies at the Lincoln Memorial, when Henry Bacon was presented the AIA Gold Medal, and, in 1926 at the 59th AIA Convention, President Coolidge received AIA members attending at the White House.

The

Great War and an Institute nadir

The European War and its aftermath, which dominated the attention

of U.S. presidents during the decade, also dominated AIA planning

and thought in the period. The Great War began in 1914 and became

an American war in 1917 when President Wilson—insisting

“the world must be made safe for democracy”—asked

Congress to declare war, which it did, on April 6, 1917. There was

no AIA Convention in 1917, though the AIA did, in its

Journal, discuss military cemeteries and the ostentatious

monuments often erected in them. This distressed Charles Moore, of

the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who

had labored with the 1901 Park Commission Plan for Washington.

“Nothing could be more impressive,” Moore wrote,

“than the rank after rank of white stones, inconspicuous in

themselves, covering the gentle wooded slopes [of Arlington] and

producing the desired effect of a vast army in its last

resting-place.”

This was a

legitimate interest of the AIA, which had planned for its members

to go into professional positions in the military, Red Cross, or

similar organizations. The British and French warned the U.S.

against sending technically trained men to the trenches. One

British architect noted that “We should indeed be fortunate if

today we had in technical service one-tenth of the architects who

lie buried on foreign soil.”

This was a

legitimate interest of the AIA, which had planned for its members

to go into professional positions in the military, Red Cross, or

similar organizations. The British and French warned the U.S.

against sending technically trained men to the trenches. One

British architect noted that “We should indeed be fortunate if

today we had in technical service one-tenth of the architects who

lie buried on foreign soil.”

To forestall that possibility, the AIA set up a card catalog of architects and drafters who desired technical service and furnished them with letters requesting that they be used in such service, but the results were less than satisfactory. “In these days of stress and patriotic endeavor,” asked AIA President John Mauran at the 1918 Convention, “when one of the principal activities of a government at war is building, why are the architects idle? That is the insistent question on the lips of every member of our profession and of the intelligent citizens who stand amazed in the face of such an anomalous situation.”

A

tender of service

The pre-war AIA Preparedness Committee had studied the technical

uses of architects and a tender of service was made in a letter to

President Wilson. With the declaration of war, many architects

offered their services without charge and their offices at cost.

The Navy Department immediately accepted, with work valued at over

$3 million. AIA President Mauran was summoned to Washington by the

Council of National Defense, which refused to accept gratuitous

service. Yet requests for help did come. When the Signal Corps

asked if the Institute could furnish 300 candidates for

lieutenancies, the AIA filled the quota in one week. Experts were

found for construction of hospitals, barracks, and housing for

shipbuilders and munitions workers. Mauran quoted one Army officer

in charge of construction work who was asked why the services of

architects, “so freely tendered, had never been utilized by

his Division; I could hardly believe my ears when he said

‘Why, for the very reason that as yet we have had no

architectural problems to contend with.’”

Mauran

continued, “The all-explaining truth is that West Point and

Annapolis have no courses in architecture, but they have courses in

engineering, and the training thus acquired has created a tradition

which seems to blind the Army engineer to the existence of another

profession, equally or better qualified to plan and design.”

(Architecture still is not taught at either West Point or

Annapolis.) Mauran assigned a larger fault to the architect,

though, asking “Have we stood shoulder to shoulder with the

budding politician in civic activities, showing that executive,

constructive grasp of civic problems which is the heritage of every

architect worth of the name; or have we held

aloof?”

Mauran

continued, “The all-explaining truth is that West Point and

Annapolis have no courses in architecture, but they have courses in

engineering, and the training thus acquired has created a tradition

which seems to blind the Army engineer to the existence of another

profession, equally or better qualified to plan and design.”

(Architecture still is not taught at either West Point or

Annapolis.) Mauran assigned a larger fault to the architect,

though, asking “Have we stood shoulder to shoulder with the

budding politician in civic activities, showing that executive,

constructive grasp of civic problems which is the heritage of every

architect worth of the name; or have we held

aloof?”

The Journal also published lists of architects serving in The U.S. Housing Corporation of the Department of Labor and the Housing Division of the Emergency Fleet Corporation, and the annual list of members for 1920 carried an asterisk by members who served, though if any necrology was ever published, one cannot find it. Whatever the survivors brought back from the war, it was what they did not bring back that Lorado Taft found disturbing. In Chicago in 1922 he said, “You and I feel this great dearth, the lack out here in the west of things beautiful and things significant—in short of the background which Europe possesses. But even worse is our lack of appreciation. I realized this as never before, realized it poignantly, in the months that I was abroad with our boys. The majority of them registered complete indifference—immunity—to the appeal of art in whatever form. For them the inheritance of the ages does not exist.”

The introspection begun by President Mauran and Lorado Taft was continued by AIA President Thomas R. Kimball, who noted in reporting to the Convention in 1920 that the AIA was “far from being numerically representative of the profession ... Why call ourselves a National Society on hardly a ten percent representation? Why attempt a comprehensive program with a Country Club organization?” Kimball noted that the AIA had lived through seven lean war years and predicted the Depression, suggesting that seven more lean years were to come.

The

Lincoln Memorial and a Roaring Twenties heyday

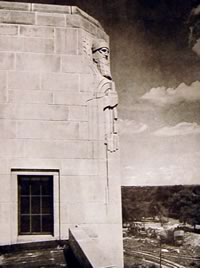

1923 will be remembered for the pageantry surrounding the

award of the Gold Medal of the Institute to Henry Bacon, designer

of the Lincoln Memorial. In ceremonies held at the memorial,

William Howard Taft, Hon. AIA, then chief justice of the Supreme

Court, introduced President Warren Harding, who presented the Gold

Medal. Harding said of Bacon, “Out of the crudest materials,

you and those who have wrought with you and after you, have given

us this creation whose simple grandeur has arrested the eyes and

thoughts of whoever loves the beautiful and appealing. You have

reared here a structure whose dignity and character have won it

rank among the architectural jewels of all time. You have brought

to your countrymen a swelling pride in the thought that they have

been capable of producing such an inspiring and such a masterful

execution.” Bacon, ever humble, in a two-paragraph acceptance

speech, acknowledged “the debt owed to those who have gone

before, whose initiative and wise counsel made possible the

erection of the Lincoln Memorial on this noble site. In their name

and in the name of all who have had at heart the building of a

memorial worthy of Abraham Lincoln, I thank you for the honor of

receiving the Gold Medal.”

Nothing any of

them could have said would have matched the spectacle of the

pageant that preceded the presentation. Members and guests dined in

a marquee at the Washington Monument end of the Reflecting Pool,

but attention was focused on the softly lighted Lincoln Memorial

and its reflection in the pool. A soft rain began to fall. Harry F.

Cunningham, then a member of the AIA Washington Chapter, viewed the

marquee across the pool from the Memorial and described the event.

“The lovely music of the Marine Band came softly across the

smooth water. Everything was smooth and still and fairylike. People

came and had to be seated, but one was not conscious that they were

people. The soft kindly rain seemed to flutter down, hesitate, and

then lay itself softly on the paving. All who were there

unconsciously spoke in whispers—and that is a significant

thing.

Nothing any of

them could have said would have matched the spectacle of the

pageant that preceded the presentation. Members and guests dined in

a marquee at the Washington Monument end of the Reflecting Pool,

but attention was focused on the softly lighted Lincoln Memorial

and its reflection in the pool. A soft rain began to fall. Harry F.

Cunningham, then a member of the AIA Washington Chapter, viewed the

marquee across the pool from the Memorial and described the event.

“The lovely music of the Marine Band came softly across the

smooth water. Everything was smooth and still and fairylike. People

came and had to be seated, but one was not conscious that they were

people. The soft kindly rain seemed to flutter down, hesitate, and

then lay itself softly on the paving. All who were there

unconsciously spoke in whispers—and that is a significant

thing.

“At one stage in the dream a portly gentleman appeared from nowhere in particular and the chief usher directed him in a whisper to a seat on the right. The portly gentleman came out of the dream and was discovered to be Mr. Taft, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court ... He smiled—he can do it so beautifully ... The usher apologized for the informality of his reception and informed the Chief Justice that he was expected to come ‘in a burst of glory’—‘No,’ said Mr. Taft, ‘I came in a Dodge.’

“A little later a fine big car, brilliantly lighted and very real, came up to the foot of the steps and the Dream having been suspended for the moment in the usher’s mind, the President of the United States was properly received. He was escorted to the steps of the Memorial and between the two central columns he awaited the ... climax of the picture. There appeared away off, at the far end of the Pool, a little speck of light that separated itself from the luminous line of the Marquee. Slowly—oh so slowly, it seemed—it grew bigger and perhaps brighter. There was music—beautiful music—soft and slippery like the rain ... I sensed rather than felt or saw, a glowing, burning something that came quietly and surely on, and on, and seemed ready to burst—but without noise, without any noise whatever ... The burning, glowing something grew bigger, and brighter, and stopped!!!”

Bacon,

the Gold Medalist, and AIA President William Faville had been

polled down the center of the pool on a barge, while members and

guests, costumed in colorful felt and carrying banners, paced the

barge on either side of the pool. Members Howard Greeley and Monroe

Hewlett had designed the lighting, the costumes, the banners, and

the procession. Cunningham noted that the 56th Convention of the

AIA, “Opened with a mallet 150,000 years old, it was concluded

with a glimpse of the Beauty that was born with the Worlds and will

die with Time.” Other Gold Medals were awarded during the era,

to Victor Laloux in 1922, to Sir Edwin Lutyens and Bertram

Grosvenor Goodhue in 1925, but no ceremony would ever again match

the Bacon one.

Bacon,

the Gold Medalist, and AIA President William Faville had been

polled down the center of the pool on a barge, while members and

guests, costumed in colorful felt and carrying banners, paced the

barge on either side of the pool. Members Howard Greeley and Monroe

Hewlett had designed the lighting, the costumes, the banners, and

the procession. Cunningham noted that the 56th Convention of the

AIA, “Opened with a mallet 150,000 years old, it was concluded

with a glimpse of the Beauty that was born with the Worlds and will

die with Time.” Other Gold Medals were awarded during the era,

to Victor Laloux in 1922, to Sir Edwin Lutyens and Bertram

Grosvenor Goodhue in 1925, but no ceremony would ever again match

the Bacon one.

Publications live though legends

die

It is easy to overlook the work of The Journal of The American

Institute of Architects during the period 1913-1926, and the

publications of the AIA Press. They established standards in beauty

and quality, producing works that have stood the test of time. None

were perhaps more important than two works by Louis Sullivan, his

The Autobiography of an Idea, and A System of

Architectural Ornament. Just as the 1900 Annual Meeting of the

AIA can be said to have resurrected the L’Enfant Plan for

Washington through the 1901 Senate Park Commission Plan, these two

books can be said to have resurrected a destitute and misunderstood

architect and given him immortality.

Sullivan’s

practice was moribund. He was broke and living on the goodwill and

funds of those who believed in him. Sullivan was no longer a

dues-paying member of the AIA when, in 1921, Charles H. Whitaker,

editor of the Journal asked him to pen book reviews for

the magazine. When this fell through, Whitaker asked for other

ideas, finally settling on a Sullivan autobiography, to be written

in the third person. It ran initially in the AIA Journal, but it

was soon clear it would be a book, along with the drawings Sullivan

was doing showing the manner in which he developed a germ of an

idea into architectural ornament. It is said that The

Autobiography of an Idea had not been out of print since, and

A System of Architectural Ornament, also reprinted,

remains a much-studied and prized volume. Sullivan saw both books a

few days before his death and was pleased.

Sullivan’s

practice was moribund. He was broke and living on the goodwill and

funds of those who believed in him. Sullivan was no longer a

dues-paying member of the AIA when, in 1921, Charles H. Whitaker,

editor of the Journal asked him to pen book reviews for

the magazine. When this fell through, Whitaker asked for other

ideas, finally settling on a Sullivan autobiography, to be written

in the third person. It ran initially in the AIA Journal, but it

was soon clear it would be a book, along with the drawings Sullivan

was doing showing the manner in which he developed a germ of an

idea into architectural ornament. It is said that The

Autobiography of an Idea had not been out of print since, and

A System of Architectural Ornament, also reprinted,

remains a much-studied and prized volume. Sullivan saw both books a

few days before his death and was pleased.

At the 1924

Convention, President William B. Faville announced, at the end of

his address: “At New York on the 16th day of February 1924, in

the fifty-eighth year of his age, Henry Bacon died. At Chicago on

the 14th day of April, 1924, at the age of sixty-five, Louis H.

Sullivan died. At New York on the 24th day of April, 1924, when

only fifty-five years of age, at the very zenith of his usefulness,

Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue died.” Those losses, in such a short

period of time, weakened the profession and, even though almost a

century has passed, must still be mourned.

At the 1924

Convention, President William B. Faville announced, at the end of

his address: “At New York on the 16th day of February 1924, in

the fifty-eighth year of his age, Henry Bacon died. At Chicago on

the 14th day of April, 1924, at the age of sixty-five, Louis H.

Sullivan died. At New York on the 24th day of April, 1924, when

only fifty-five years of age, at the very zenith of his usefulness,

Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue died.” Those losses, in such a short

period of time, weakened the profession and, even though almost a

century has passed, must still be mourned.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page