ADVENTURES IN ARCHITECTURE: THE SERIES

Il Duomo: Brunelleschi and the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore

Episode 11—The Passing of Filippo

by Jim Atkins, FAIA, FKIA

Summary: Filippo Brunelleschi died in 1446, years before the immense lantern adorning his magnificent Duomo was completed in Florence. Though mourned and honored on his passing, amazingly, even while his work became a symbol of the emerging Renaissance, Brunelleschi eventually faded into the background of history for almost five centuries.

In the last episode, the Opera held a competition in 1436 to select a winning design for the lantern that would sit atop the great dome. Filippo went up against an array of competitors including his old rival Ghiberti; a woman, to the shock and dismay of all the men; a leadbeater; and his own hired carpenter. This was no doubt the Renaissance version of today’s design-build interview.

Filippo won again, but with a mandate to cool his temper and undergo committee-driven value engineering. Ghiberti finally moved on, but the hired carpenter proved to be a testy rival, remaining engaged with the lantern construction and eventually replacing our man as capomaestro. Work progressed much more slowly than the great dome, eventually taking almost twice as long. Filippo commanded the effort in the beginning, but on April 15, 1446, with the lantern still in the early stages of construction, after a short illness Brunelleschi died at the age of sixty-nine.

Return with us now to the 15th century, as the people of Florence lay to rest their great hero. They celebrated him in death more than they did in life, and he would be forever known as the genius who built the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore. Return with us now to the 15th century, as the people of Florence lay to rest their great hero. They celebrated him in death more than they did in life, and he would be forever known as the genius who built the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore.

A busy schedule

During Filippo’s last years, he was quite busy with commissions. In addition to his work on the lantern, he occasionally served as a consultant on the Chapel of the Holy Girdle in Prato. In Pisa, he oversaw work strengthening the banks of the Arno River. He designed a pulpit for the church of Santa Maria Novella, which would later be carved in marble by Buggiano. He remained involved with the reconstruction of the basilicas of S. Lorenzo and S. Spirito.

Filippo was filled with energy and creativity. He continued his involvement with the military, working on fortifications in the Signa and Chianti areas as well as a castle in Rimini. His work in military fortifications included strategic city planning.

He also was quite successful with his theatrical devices, creating machinery capable of flying angels over the crowd with cables and pulleys, and emulating the Holy Ghost with fire billowing overhead. These inventions were installed in four churches: S. Felice, S. Maria del Carmine, SS Annunziata, and S. Spirito. This work was permanently installed and used at annual religious festivals.

His actual involvement in these venues is disputed, alleged by some to be minimal and others to be extensive. In any case, he was instrumental in developing these devices, and it was no doubt his clockmaking skills and his work on the dome hoisting and placing materials that enabled these talents.

Inheritance

In March 1446, Filippo attended the consecration by Cardinal Antoninus of the first stone to be placed in the lantern. Barely one month later, he passed away. He died in the house where he had lived his entire life, just 10 days after the first huge marble column arrived on site at his project at S. Spirito.

He left his house and just over 3,400 florins to his adopted son, Andrea il Buggiano. An inventory of his possessions at the time of his passing gives us a glimpse inside this great man. His furniture was crude and simple, yet his clothing was rich and elegant. There was a manuscript of the Bible, a religious painting, drawings, carving tools, and plaster figures. The attic contained an organ without pipes; perhaps used as an architectural model for the organ at Santa Maria del Fiore. There were many vases of verdigris, and in the cellar there were more vases, an iron ball, and three shields. The place resembled more a workshop and laboratory than a residence. He left his house and just over 3,400 florins to his adopted son, Andrea il Buggiano. An inventory of his possessions at the time of his passing gives us a glimpse inside this great man. His furniture was crude and simple, yet his clothing was rich and elegant. There was a manuscript of the Bible, a religious painting, drawings, carving tools, and plaster figures. The attic contained an organ without pipes; perhaps used as an architectural model for the organ at Santa Maria del Fiore. There were many vases of verdigris, and in the cellar there were more vases, an iron ball, and three shields. The place resembled more a workshop and laboratory than a residence.

The traces of his personal life would later fade from history, except for limited documentation available on the construction of the dome. However, the inheritance he left for history and architecture would slowly be uncovered and rediscovered in the late 19th century.

The funeral and interment

The sudden passing of Filippo brought immense grief to the people of Florence. It is said that even his enemies mourned his death. As the reality set in, the city began preparing to celebrate the passing of its champion of the great dome of Santa Maria del Fiore.

The funeral obsequies were held in Santa Maria del Fiore. Brunelleschi lay in repose beneath the great vault of his own creation. His bier was surrounded by candles, and he was wrapped in white muslin. The thousands of mourners paying tribute included the wardens of the Opera, the consuls of the Wool Guilds, and the masons who labored to construct the cathedral.

A death mask was made of his face, an honor ordinarily reserved for royalty. It can be seen today in Florence in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo. Later, his adopted son Buggiano would carve a marble bust of Brunelleschi, at his own expense, for display in the cathedral.

Filippo’s body was removed to the campanile adjacent to the cathedral, where it remained until the following December. Some say that he was buried there, and others say that he was only in repose there while his final resting place was being disputed. In any event, the Arte della Lana ultimately decided that he should be buried under the floor of the cathedral. This great honor was granted only to distinguished individuals. Filippo’s body was removed to the campanile adjacent to the cathedral, where it remained until the following December. Some say that he was buried there, and others say that he was only in repose there while his final resting place was being disputed. In any event, the Arte della Lana ultimately decided that he should be buried under the floor of the cathedral. This great honor was granted only to distinguished individuals.

He was buried in a tomb beneath the south aisle, near the location where Fioravanti’s original model of the dome had been housed for so long. The inscription on the crypt was covered over, perhaps to conceal the tomb from his enemies. Its location was not rediscovered until 1972 during excavations in search of the foundations of the old cathedral, Santa Reparata. The inscription on the tomb reads:

“Corpus Magni Ingenii Viri Philippi Brunelleschi Fiorentini”

“Here lies the body of the great ingenious man Filippo Brunelleschi of Florence”

When the tomb was rediscovered in 1972, the remains were exhumed and forensics conducted. The tests concluded that he was short in stature even for a man of the 15th century; he was no taller than 5 feet 4 inches. However, it was determined that he had a large cranial capacity. This is confirmed by the death mask commissioned at the time of his passing.

Transformation

Brunelleschi’s forgotten crypt emphasizes the anonymity of the architects of the Middle Ages. Today, the great architects in history are widely celebrated, yet those of the time of Brunelleschi were poorly documented, and many were largely forgotten. This has been attributed by some as a prejudicial act by medieval authors who regarded architects as laborers, and thus uneducated.

This notoriety changed during the Renaissance, acknowledging architects and their artistry in a more realistic dimension. Ross King describes it well in his book, Brunelleschi’s Dome: This notoriety changed during the Renaissance, acknowledging architects and their artistry in a more realistic dimension. Ross King describes it well in his book, Brunelleschi’s Dome:

Filippo’s work at Santa Maria del Fiore set architects on a different path and gave them a new social and intellectual esteem. Largely through his looming reputation, the profession was transformed during the Renaissance from a mechanical into a liberal art, from an art that was viewed as “common and low” to one that could be regarded as a noble occupation at the heart of the cultural endeavor.

His soul and singular virtues

The accomplishments of Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi reach far beyond the dome of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Fiore. His experience as a goldsmith, sculptor, and clockmaker, and his exploits in the Roman ruins make us envious of his rich life experiences.

His many years constructing the great dome, persevering great challenges from both man and materials, encourage us to persist in our own endeavors. His enthusiasm for life, evidenced by his prolific trail of inventions and accomplishments, is a model for all who strive to find a meaning and purpose for their existence.

Brunelleschi personified what we all endeavor to accomplish in our lives and in our work. Operating at his own level, with only available resources and occasional opportunities, he achieved greatness beyond what was expected or thought possible. His life and accomplishments truly compose a model worth our study and contemplation.

In the cathedral beneath Buggiano’s sculpted figure of Brunelleschi is an inscription by the humanist Carlo Marsuppini:

Just how eminent Filippo the Architect was in the arts of Daedalus is demonstrated by the marvelous shell of this celebrated temple, and by the many machines invented by his divine genius. Wherefore because of the excellent qualities of his soul and singular virtues, on the 17th day of April, 1446, his well-deserving body was laid in this ground by order of his grateful fatherland.

May you rest in peace, Filippo Brunelleschi

Next month

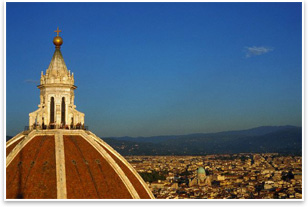

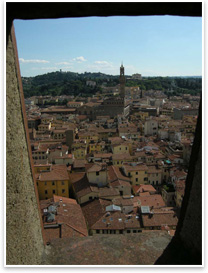

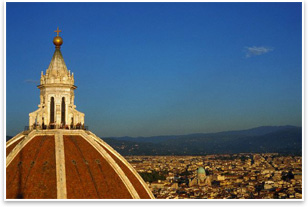

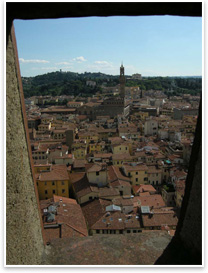

Join us next month when we explore the Basilica of Santa Maria del Fiore as it exists today. The cathedral with its great dome, the Bapistery of San Giovanni, and Giotto’s Campanile await us as we become Florentine tourists and explore this great architectural treasure.

Weave your way through the crowd in the festive Piazza del Duomo to the side entrance of the Basilica where you enter as the workers did six centuries ago. Purchase your ticket and we’re on our way. It will be an experience that you will never forget.

Witness the enduring architecture of Filippo Brunelleschi and climb the 463 steps inside the shell of the dome to reach the lantern on top. Gaze from the lantern base at the vibrant Florentine panorama as you feel the sun on your face and the Tuscan breeze in your hair.

Don’t miss the last episode of this adventure in architecture. And until next time, good luck out there.

|

He left his house and just over 3,400 florins to his adopted son, Andrea il Buggiano. An inventory of his possessions at the time of his passing gives us a glimpse inside this great man. His furniture was crude and simple, yet his clothing was rich and elegant. There was a manuscript of the Bible, a religious painting, drawings, carving tools, and plaster figures. The attic contained an organ without pipes; perhaps used as an architectural model for the organ at Santa Maria del Fiore. There were many vases of verdigris, and in the cellar there were more vases, an iron ball, and three shields. The place resembled more a workshop and laboratory than a residence.

He left his house and just over 3,400 florins to his adopted son, Andrea il Buggiano. An inventory of his possessions at the time of his passing gives us a glimpse inside this great man. His furniture was crude and simple, yet his clothing was rich and elegant. There was a manuscript of the Bible, a religious painting, drawings, carving tools, and plaster figures. The attic contained an organ without pipes; perhaps used as an architectural model for the organ at Santa Maria del Fiore. There were many vases of verdigris, and in the cellar there were more vases, an iron ball, and three shields. The place resembled more a workshop and laboratory than a residence. Filippo’s body was removed to the campanile adjacent to the cathedral, where it remained until the following December. Some say that he was buried there, and others say that he was only in repose there while his final resting place was being disputed. In any event, the Arte della Lana ultimately decided that he should be buried under the floor of the cathedral. This great honor was granted only to distinguished individuals.

Filippo’s body was removed to the campanile adjacent to the cathedral, where it remained until the following December. Some say that he was buried there, and others say that he was only in repose there while his final resting place was being disputed. In any event, the Arte della Lana ultimately decided that he should be buried under the floor of the cathedral. This great honor was granted only to distinguished individuals. This notoriety changed during the Renaissance, acknowledging architects and their artistry in a more realistic dimension. Ross King describes it well in his book,

This notoriety changed during the Renaissance, acknowledging architects and their artistry in a more realistic dimension. Ross King describes it well in his book,