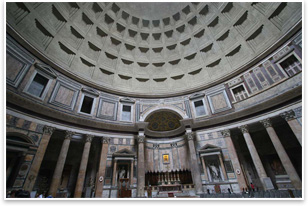

ADVENTURES IN ARCHITECTURE by James Atkins, FAIA, FKIA Summary: In our last episode, we followed Filippo and his artist friend, Donatello, as they explored the ancient ruins of Rome carefully studying construction techniques, measuring, and sketching their findings. Leaving the locals to think they were vagrants in search of abandoned treasures, they remained in their quest to learn about the superior Roman building technology for almost 13 years. Of particular interest was the Pantheon, the domed temple built by the emperor Hadrian in 125 AD. Knowing that Santa Maria del Fiore would eventually include a dome, Filippo measured and studied the Pantheon to learn of its design and construction. Filippo eagerly responded to the Opera’s competition for the new dome for Santa Maria, announced in 1418, and he was selected, along with his arch-rival Lorenzo Ghiberti, as a capomaestro, or architect-of-record. Santa Maria’s supporting walls had been built without buttresses or perpendicular bracing walls, with the assumption that tension rings, or chains, could be used to counter the outward forces on those walls. However, the design and materials for the rings had yet to be determined. Join us as Filippo takes charge in the development of the dome design and the rings that would support it. Such a task had never before been attempted, and completion of the project would require extraordinary talent and resolve. Let’s return to the 15th century as Filippo becomes lord of the rings.

Given his limited influence in Florence and his lack of experience on a structure of such magnitude, he was ridiculed by the Opera and the townspeople. Ultimately, the Opera began to assume that such a structure could not be built, and they believed the earlier masters were naïve in thinking it could be done in the first place. Filippo protested this conclusion, and the wardens responded by demanding he explain how it could be built. He continued to assert his position of building without centering, and twice he was angrily thrown out of the meetings by the wardens, who called him a madman who uttered nonsense. Filippo was quite humiliated and ashamed to go about the city. Nonetheless, he persisted with his beliefs and continued patiently to assert his design concept, using great diplomacy while curbing his volatile temper. (Ah, the quest for a project can guide us in remarkable ways!) After a time, observing his continuing resolve, the wardens began to accept Filippo’s position and asked him to demonstrate his proposed method by using it in the construction of a small chapel in Florence named San Jacopo di Borgo Oltrarno, where a dome was scheduled to be built. Filippo accepted the request and demonstrated in this much smaller scale his proposed construction approach. The project was a success, and it was the first project in Florence to be vaulted using such a method. Afterwards, the wardens requested a more detailed explanation of his proposed plan, and he responded with great patience and precision describing the process in great detail. They asked for his specifications in writing, and he produced a written work that was bound in a book and used to satisfy the lenders and suppliers of the marble and timber. (Hmmm, documentation … it was important then, it is important now.) The specification below is excerpted from the book, The Life of Brunelleschi, by Antonio Manetti, originally written in the 1480s and translated by Catherine Enggass and published by The Pennsylvania State University Press in 1970.

Filippo’s specification was given in 1420, and it instilled confidence in the Opera and the townspeople, giving him great credibility and confidence. The perception by the wardens of his skill and talent had to be recognized for him to get the job. He had no relevant past projects to use as examples, and he had to rely on his persuasive abilities to make the difference. The sandstone chains

Although the rings were considered to be “hoops” whose tensile forces counteracted the outward push of the sides of the dome, Giovanni and Michelle Fanelli, in their book, Brunelleschi’s Cupola, state:

It has a nice ring to it After the stones were rough-cut, they were tested for monolithic integrity with a hammer. A good beam would have a ring, not unlike striking metal. A dull sound would indicate a fissure or crack in the material.

The beams that made up the rings were tied together at their connecting ends with iron clamps. The forged iron clamps were then coated with lead to prevent rust and subsequent degradation. There would be four stone chains in total, unlike the specification that called for six. A fifth ring would be made of wood. The chains were spaced about 35 feet apart vertically, and the upper chains were tilted in with the curve of the dome, making them much more difficult to install. Initially, four wooden chains were planned, but as in architecture these days, material unavailability and subsequent design modifications overrode the original concept. The only wooden chain, installed 25 feet above the bottom stone chain, would prove to be quite challenging for several reasons.

Although finding the chestnut beams proved difficult, curing them would be as daunting. They first had to be soaked in water for a month, and then they were buried in ox dung for almost as long. They were then placed on a bed of ashes and protected from the elements for several years. (Perhaps our limited supply of oxen has inhibited our advancements in building technology.) Project delivery scheduling by contemporary methods would place the wooden chain on the critical path, and it is not surprising that only one wooden chain was installed. Some assert that Filippo had an ulterior motive for using the wooden chain: a ploy to undo his dreaded rival, Lorenzo. The final blow The wooden chain apparently gave Filippo the idea for a scheme to attack Lorenzo’s credibility and do in his rival once and for all. Feigning an illness, Filippo took to his bed and did not return to the site except in bandages. With Filippo incapacitated, responsibility for the wooden chain fell to Lorenzo. Since Filippo had not revealed his design, Lorenzo did not know what to do. Filippo’s condition appeared to worsen, and Lorenzo finally gave instructions as best he could, but he was not aware of the complex connections that Filippo had designed. This underscores the importance of effective communication among team members, not to mention a structured submittal review process. After only a few wooden beams had been installed in the ring, Filippo made a dramatic recovery and reappeared on the site, immediately condemning the work of Lorenzo. The work was removed, and Lorenzo was exposed and disgraced before the wardens and the townspeople. Filippo took charge and began completion of the wooden chain. Filippo’s salary was increased, and Lorenzo’s was initially suspended, later to be reinstated at a fraction of Filippo’s. Lorenzo would become less and less involved with the dome and ultimately spend most of his time on other commissions. (Such mischief would not be possible today, as there are far too many lawyers among us itching to pursue defamation.)

Continuous iron chains A model role The question arises: If this man of practical education and limited technical resources could do the great things he did in that era of antiquity, what is the potential for architects today with our magnificent universities, profound technologies, and unlimited resources? Perhaps we have it too easy. We surf the Web looking for answers rather than answering; we rely on others to solve rather than solving. We should quest for problems and challenges that yet have no answers or solutions. We should seek to become lord of our own rings of accomplishment. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Il

Duomo 4: The Inspiration of Rome

› Il

Duomo 3: The Architect

› Il

Duomo 2: The Competition

› Il

Duomo 1: Brunelleschi and the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore

Jim Atkins is a principal with HKS Architects in Dallas, where he is involved with project management, construction services, and risk management. He is a student of the great architects in history who have taken their talents beyond architecture.

Next Month

Don’t miss the next episode as we continue the adventures of Filippo Brunelleschi and the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore. The tension rings were an important component, but other, lesser known innovations in Brunelleschi’s design play a critical role in the construction of Il Duomo.

The dome-within-a-dome construction gave the structure integrity that may not have been originally anticipated or relied upon in its original design. It also provides a path of ascent to the lantern. The herringbone bond in the brick coursing is also instrumental in giving the dome its life. As construction ascended past the critical angle of 30 degrees—where the inward forces were challenging the vault’s structural integrity—something had to be done to keep the brick in place until the mortar cured. The bond proved to be an effective solution. Also, horizontal arches constructed between the two shells, which were not included in the original plans, played an important role in the sequence of construction.

Meanwhile, until next time, good luck out there.

Captions

(Photos by the author and Sook Kim, his wife.)

Photo 1. Interior of the

Pantheon

Illustration 2. The Italian Braccia measurement

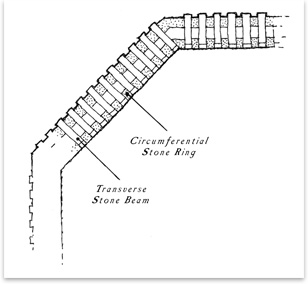

Illustration 3. The sandstone chain

Photo 4. View of drum galleries above and below the circular windows

Photo 5. The beams protrude just above the circular windows and below

the tile roof

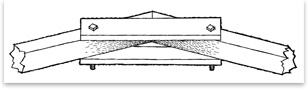

Illustration 6. Oak splices on the chestnut beams

Photo 7. The wooden chain as seen between the two shells.

References

Brunelleschi: Studies of His Technology and Inventions, Frank D. Prager and Gustina Scaglia, Dover Publications, 1970.

Brunelleschi’s Cupola: Past and Present of an Architectural Masterpiece, Giovanni Fanelli and Michele Fanelli, Mandragora, 2004.

Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture, Ross King, Penguin Books, 2000.

Filippo Brunelleschi, Engenio Battisti, Elicta Architecture, 2002.

First published in the USA in 1981 by Rizzoli International Publications.

Renaissance Engineers: From Brunelleschi to Leonardo da Vinci, Paolo Galluzzi, Giunti Publications, 2004.

The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World, Paul Robert Walker, Perennial-Harper Collins Publishers, 2003.

Vitruvius: Ten Books on Architecture, Edited by Ingrid D. Rowland and Thomas Noble Howe, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Perception

Perception The specification continued in great detail explaining how the two shells would be tied together, as well as how the rainwater would be managed. The unit of measurement was the braccia, a measurement derived from the distance of the elbow to the fingertip, or about 23 inches.

The specification continued in great detail explaining how the two shells would be tied together, as well as how the rainwater would be managed. The unit of measurement was the braccia, a measurement derived from the distance of the elbow to the fingertip, or about 23 inches. The chains were somewhat elaborate, with two horizontal rings

of stone concentrically placed. These two rings were connected

with transverse connecting beams, attached on three-foot centers

with iron clamps and dovetailed into the rings. The completed assembly

formed a sturdy, rigid lattice that had to follow the inward curve

of the masonry.

The chains were somewhat elaborate, with two horizontal rings

of stone concentrically placed. These two rings were connected

with transverse connecting beams, attached on three-foot centers

with iron clamps and dovetailed into the rings. The completed assembly

formed a sturdy, rigid lattice that had to follow the inward curve

of the masonry. So it appears that the “tension” rings were likely not performing in that manner at all, but instead acting more as a system for bonding the masonry.

So it appears that the “tension” rings were likely not performing in that manner at all, but instead acting more as a system for bonding the masonry. Each of the eight sides of the concentric rings consisted of 12 beams, each 7 feet, 6 inches long by 1 foot, 5 inches thick, for a total of 96 beams. The connecting transverse beams in the lowest ring protruded through the sides of the dome just above the round windows and are visible from below.

Each of the eight sides of the concentric rings consisted of 12 beams, each 7 feet, 6 inches long by 1 foot, 5 inches thick, for a total of 96 beams. The connecting transverse beams in the lowest ring protruded through the sides of the dome just above the round windows and are visible from below. Originally intended to be of oak and 20 feet in length, supply limitations would bring about a substitution of chestnut, with three wooden beams required on each leg of the octagon, or 24 in all. However, they would be connected with oak plates.

Originally intended to be of oak and 20 feet in length, supply limitations would bring about a substitution of chestnut, with three wooden beams required on each leg of the octagon, or 24 in all. However, they would be connected with oak plates. Only one wooden chain was installed in the dome, and it is visible

today on the ascent up the stairs between the two shells. (And,

although Filippo was certain that he had dealt the final blow to

Lorenzo, he would later find out otherwise. Don’t miss the continuing antics of Lorenzo in a future episode.)

Only one wooden chain was installed in the dome, and it is visible

today on the ascent up the stairs between the two shells. (And,

although Filippo was certain that he had dealt the final blow to

Lorenzo, he would later find out otherwise. Don’t miss the continuing antics of Lorenzo in a future episode.)