ADVENTURES IN ARCHITECTURE by James Atkins, FAIA, FKIA Summary: In our last episode, we followed Filippo Brunelleschi as he began as a goldsmith apprentice, working among the smoking furnaces and creating bronze reliefs and magnificent wood carvings. His studies in machines and motion and his clock-making enabled him to build what is considered to be the first alarm clock. He was accomplished at sculpting and painting, and he resurrected the forgotten principles of perspective drawing, building a perspective machine to demonstrate its effectiveness and realism. His life study in the arts and physical sciences prepared him for the task of designing and constructing the great dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, but perhaps the greatest single source of preparation and training was gained through his explorations over many years in Rome with his friend, the artist Donatello, studying and measuring the ancient Roman ruins. The great accomplishments of the Romans in design and technology had been condemned and discarded along with its unpopular pagan beliefs and practices. Nonetheless, Rome in the 15th century was filled with architectural remnants and structures; many that were relatively unspoiled. Join us as we accompany Filippo and Donatello in their quest to learn about the technical knowledge and achievements of the Romans. Our adventure in architecture continues as our two explorers investigate and experience the inspiration of ancient Rome. Shortly after Filippo lost out on the baptistery door competition in 1401, he set out for Rome with his sculptor friend, Donatello, a younger chap with an even greater temper than Filippo. Over the next 13 years, they would move about Rome, living like vagrants, digging among the ancient ruins, and learning about the great Roman accomplishments and technology, all the while leaving the locals to believe that they were mere opportunists, looking to find abandoned treasures. Roman technology was superior to their predecessors, the Greeks, in many ways. In addition to great public buildings, they built an infrastructure that allowed Rome to become the largest city in the world. Roads and bridges were built to ease travel and increase trade. Aqueducts were built to supply the city with fresh water, and parts of them are still in use today. The primary use of the water was for the drinking fountains and the baths. However, a secondary use was to operate the most advanced sewer system in the world.

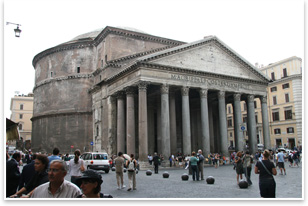

Filippo’s actual intentions at the time were unknown even to his friend Donatello. He did not reveal his true motives as they went about their work, and he recorded his discoveries by using cryptic symbols and Arabic numbers, concealing his findings to those around him. Remember, this was before the protection of patent and copyright laws, and the best way to protect intellectual property at that time was through disguise and concealment. Leonardo di Vinci used the same technique very effectively. One of the measurements that Filippo made were of the three architectural orders—Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian—invented by the Greeks and perfected by the Romans, whose proportions were governed by precise mathematical ratios. Filippo respected these disciplined design principles, and his mission in Rome was to study and investigate the ancient ruins to learn the intricacies of the great technology and accomplishments of the Roman Empire and how they could be applied to the modern technology of the 1400s. The magnificent Pantheon Of significant interest was the Pantheon, the Emperor Hadrian’s monument to all gods, built around 120 A.D. The dome spanned 142 feet, with a height of 143 feet. After 1,300 years, it remained the largest dome in existence. The only reason that it was still around and had not been plundered was that it had been converted to a church, and it is now called Santa Maria dei Martiri.

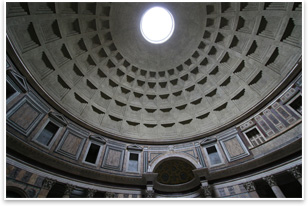

At the base of the dome the horizontal stress is greatest, and the lower walls of the structure are 23 feet thick. As the walls rise to the top of the dome, they decrease to 2 feet thick and open with an oculus in the center. Its physical presence is breathtaking.

The astounding difference is that engineers today maintain that a concurrent design of unreinforced concrete used in the same configuration will not support its own weight. The Romans had apparently produced concrete with a tensile strength sufficient to accomplish this task. This great edifice no doubt impressed Filippo with ideas for spanning the dome of the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. He spent much time studying and measuring the structure, and his knowledge gained would later prove to be helpful in creating his immaculate design solution for Il Duomo. The explorations Filippo measured every structure that he studied: almost every one in Rome at that time. They were rough drawings, but they recorded the basic information of the construction details; building widths, heights, wall thicknesses, and the like. The drawings were made on strips of parchment, the velum of the time. He also studied the vaulted works of the Romans and the technology that they used to create large spans. Many examples of Roman vaulting exist today.

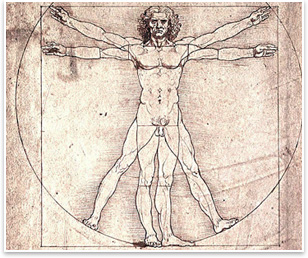

The plumb line, T-square, and mason’s level came from these developments. These tools and the mathematics used at the time facilitated construction using the ratios, or proportions, that guided the design of the cornices, friezes, pediments, moldings, and architraves that make up this celebrated era in architecture. The Romans were adroit students of architecture and construction. The ancient Roman architect, Vitruvius, wrote 10 books on architecture that miraculously survived into the Renaissance. One volume addresses the proportions of buildings, and Vitruvius believed that buildings should be based on human proportions. He believed that the human body was perfect, and he validated his belief by writing that a human’s arms and legs, when extended, related to the square and the circle, two pure geometric forms. This was graphically illustrated by Vitruvius; however a more famous illustration by Leonardo di Vinci prevails, known as the Vitruvian Man.

His reputation was well established by then, since he had done much work for the Opera del Duomo in planning the dome and had other successful commissions as an architect and a goldsmith. They summonsed him and would not let him go, keeping him busy in consultation to the point of paying him 10 gold Florins. Even back then, money was a persuasive language understood by all. Filippo responded by recommending that they convene an assembly of masons, architects, masters, and engineers to consult on how such a great dome could be built. Having given that advice, he left for Rome. The Opera followed up on his suggestion, but it was not until the following year that they took action. Filippo held fast to his proposal of building the dome without buttresses, and this revolutionary concept was very popular with the Florentines. The essence of the design lay with the rings; the tensile restraints used to counteract the forces pushing outward on the base of the dome. Although his plan was revolutionary, he believed that it could be accomplished. As the day of submission drew near, he knew that he would ultimately be given the chance to explain to the Opera the concept of his dome, held intact by the tension rings, and constructed without armature or centering.

| ||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Il Duomo3: The Architect

› Il Duomo2: The Competition

› Il Duomo1: Brunelleschi and the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore

Jim Atkins is a principal with HKS Architects in Dallas, where he is involved with project management, construction services and risk management. The dome designs that he has worked on were sold by his marketing partners. All he had to do was administer construction services.

Next Month

Join us next month as we observe Filippo in his attempt to sell the Opera on the concept of the tension rings. No construction of a dome in past history had used such technology, and it had yet to be proven in Florence or elsewhere. Ultimately, there would be four rings or chains made of stone, and one ring of wood, creating a structure that would allow construction to proceed without centering and eliminating the need for buttresses in the supporting cathedral walls.

This technology was not known to anyone at the time. How would Filippo convince the Opera del Duomo that the ring concept would be workable? Join us as our silver-tongued Florentine reaches new heights in his marketing achievements. Brunelleschi had no past projects to use as built examples, and structural engineering calculations to prove worthiness had not yet come into existence. It would all rest on his ability to convince the wardens of the Opera that it could be done. If our hero succeeds, he will be greatly celebrated and admired. If he fails, well, you get the picture.

Join us as we find out if Filippo will become lord of the rings and experience success with his innovative dome design, or if he becomes just another capomaestro who came and went. Be sure not to miss this riveting episode.

Until next time, good luck out there.

Captions

(Photos by the author and his wife.)

1. The Roman Forum

2. The Pantheon in Rome.

3. The Oculus in the Pantheon

4. Vaulted Structure in the Roman Forum

5. Leonardo di Vinci’s Vitruvian Man.

References

Brunelleschi: Studies of His Technology and Inventions, Frank D. Prager and Gustina Scaglia, Dover Publications, 1970.

Brunelleschi’s Cupola: Past and Present of an Architectural Masterpiece, Giovanni Fanelli and Michele Fanelli, Mandragora, 2004.

Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture, Ross King, Penguin Books, 2000.

Filippo Brunelleschi, Engenio Battisti, Elicta Architecture, 2002.

First published in the USA in 1981 by Rizzoli International Publications.

Renaissance Engineers: From Brunelleschi to Leonardo da Vinci, Paolo Galluzzi, Giunti Publications, 2004.

The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World, Paul Robert Walker, Perennial-Harper Collins Publishers, 2003.

Vitruvius: Ten Books on Architecture, Edited by Ingrid D. Rowland and Thomas Noble Howe, Cambridge University Press, 1999.