ADVENTURES IN ARCHITECTURE by Jim Atkins, FAIA, FKIA Summary: In our last episode, the wardens of the Opera del Duomo, the program managers for the wealthy wool merchants who were financing the new cathedral, Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore, elected both Filippo Brunelleschi and his arch rival Lorenzo Ghiberti as capomaestros, today’s rough equivalent to the architect-of-record, to build the new cathedral dome. The men were the successful winners in a design competition that attracted artisans from all of Tuscany.

But who was this young Florentine? How is it that this local artisan emerged to become a capomaestro? What path led him to these lofty concepts of design and technology? The young Filippo, a native Florentine and the son of a notary, was not interested in his father’s business, and instead aspired to be an artisan. His journey to become an architect and a capomaestro on the famous dome is a story of astonishing talent and diverse capabilities. Join us as we explore the life of this extraordinary man. A goldsmith and sculptor Filippo had learned to read and write at an early age as well as use the hand-held calculator of the time known as the abacus. He had an interest in drawing and painting, and his work was much admired. He mastered the trade quickly and became accomplished at ornamental reliefs, precious stone polishing, and enamel. He was a talented wood carver, and he created works in bronze. He excelled for someone his young age and soon won commissions for silver figures, carved wooden statues, engraved silver ornaments, and cast bronze reliefs. The work of a goldsmith was often challenging, working in a hazardous environment among the rancid, smoking furnaces, and working with toxic materials such as lead and sulfur. Nonetheless, Filippo learned his trade quickly and was elevated to the level of master goldsmith by the time he was 21.

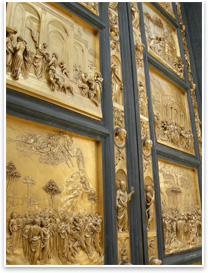

One of the worst outbreaks of the plague, which had visited the city multiple times since the mid-1300s, had recently reduced the city’s population by 20 percent. The Guild of Cloth Merchants sponsored the new doors either to celebrate the plague’s end or mollify the gods that they believed had brought the devastation, or possibly both. Filippo, who had left Florence to escape the plague, returned to enter the competition. After all, cast bronze reliefs were one of his specialties, and he had executed a number of commissions for churches in the area. The field included seven competitors made up of sculptors and goldsmiths, but the two local favorites were Filippo and Lorenzo Ghiberti. The contestants were required to make sample panels for the judges to consider, a process emulated today by the shop drawing and sample submittal process. Although Filippo was the favored contender, the award went to both men equally with the caveat that they work as partners. Filippo stubbornly refused unless he was given sole command of the work. The judges held to their decision, Filippo refused to budge from his position, and the entire commission went to Lorenzo. Filippo was bitter about the missed opportunity, and the incident would launch a rivalry between the two men that would persist throughout their lives.

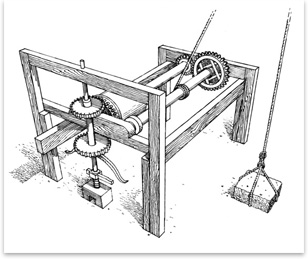

Machines had existed and were already in use on the cathedral site before Filippo produced his work, but they were not capable of moving the weights required for the cupola materials. In 1418, the Opera del Duomo launched a competition for lifting devices. Filippo eagerly responded and began designing what would later be recognized as one of the most significant accomplishments with machinery in the Renaissance. He designed and built a hoist that exceeded all previous technology known to the Florentines. It was powered by two oxen, and it had a gear reversing capability that allowed the oxen to propel the device both upward and downward while going in the same direction, thus significantly increasing its efficiency. Up until this time, the oxen had to be unhitched and reversed in order to lower the hoist. Payload could now be delivered and the bucket returned to the ground in 10-minute intervals.

Meanwhile, Filippo had never been paid any of the 200 Florins promised to the winner of the dome design. Many architects today may have had a similar experience. However, the Opera paid him 100 Florins for the development of the hoist. Perhaps this was to make up for stiffing him on his fee the first time around. Although his new hoist could move loads vertically, it could not move them laterally. The beams for the stone tension rings would obviously need to be moved laterally, once they were hoisted, in order to place them properly. So, in 1423, the Opera launched yet another competition for such a mechanism. Filippo met the challenge by designing a hoist known as the castello. Consisting of counterweights and hand operated screws that moved the payload on a sliding track, the heavy sandstone ring components could be placed with accuracy. The overall design of the castello is interestingly similar in design to our tower cranes in use today. These magnificent inventions would survive Philippo to be used on future projects, and they would be heralded as being among his greatest accomplishments.

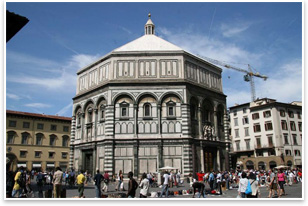

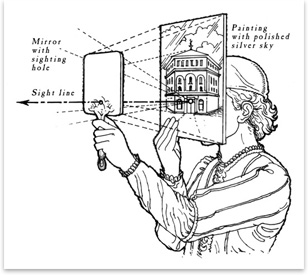

To demonstrate the effect of drawing in perspective, Filippo painted the Baptistery of San Giovanni from about six feet inside the center door of Santa Maria del Fiore. The painting included everything that could be seen from his positioned location. Instead of painting the sky, he affixed a plate of polished silver. He carved a peephole in the painted panel at the perspective vanishing point. Standing at the same location where he painted the view, he demonstrated the accuracy of perspective drawing by holding the painted panel facing away, with the panel held up to his eye to peer through the hole. With his other hand he held a mirror at arms length in front of and facing the painting so that he was looking directly into the mirror at the reflection of the painting. The view through the hole into the mirror revealed the painting, drawn in perfect perspective, in the place where the subject of the painting would be viewed. The polished silver plate reflected the actual sky complete with drifting clouds. The view was so realistic that the viewer could not tell the difference between the painted scene and the actual image of the building’s shape and proportion.

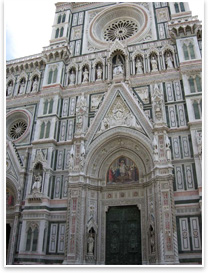

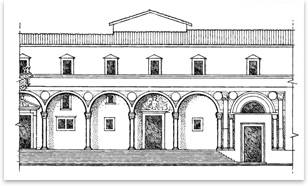

The Innocenti Arcade design During this time off, Filippo received and began work on his first great commission in the style of the Renaissance, the Ospedale degli Innocenti, or the “Hospital of the Innocents,” an orphanage financed by Francesco Datini, a wealthy merchant in Prato. Filippo affixed his imprint on the existing well-used loggia design, or porch, and his arches and columns defined a new style in architecture. He used the ancient Roman architectural elements, the arches, the architraves, the columns, and the capitals, to form a leaner and simpler design. His new loggia was powerful, and it defined and emphasized the adjacent public space before it, making it a grander space.

Filippo’s path from young master goldsmith to capomaestro on the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore was one of incredible experiences and development. He first mastered the artistry of drawing and painting, then woodcarving and sculpting, with an intense drive to understand the physical works of mechanics and motion. He was much more than an artist. He was a lifetime student of the art and architecture that surrounded him. His quest was to know and understand all that had been accomplished in the present and in the past. Next Month Join us next month when we experience the adventures of Filippo and Donatello as they explore the ancient ruins of Rome. We will follow their exploits as they pose as treasure hunters while they learn about the incredible advances of the Romans and their accomplishments with concrete, masonry, and “column and arch” design. Be sure not to miss the upcoming exploits of this Renaissance genius in his quest to build Il Duomo. Until next time, good luck out there.

|

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Il Duomo: The Competition

› Il Duomo: Brunelleschi and the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore

Jim Atkins is a principal with HKS Architects in Dallas where he is involved with project management, construction services, and risk management. He is a student of Renaissance architects and architecture, and he enjoys writing about them.

Photos

Photo 1. Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore

Photo 2. The Baptistery of San Giovanni

Photo 3. The Doors of Paradise

Photo 4. Brunelleschi’s 3-Speed Hoist

Photo 5. The Center Doors of Santa Maria del Fiore

Photo 6. Brunelleschi’s Perspective Machine

Photo 7. Example of the Innocenti Arcade Design.

Photos by the author and his wife. Illustrations by Jim Anderson.

References

Brunelleschi: Studies of His Technology and Inventions, Frank D. Prager and Gustina Scaglia, Dover Publications, 1970.

Brunelleschi’s Cupola: Past and Present of an Architectural Masterpiece, Giovanni Fanelli and Michele Fanelli, Mandragora, 2004.

Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture, Ross King, Penguin Books, 2000.

Filippo Bruneleschi, Engenio Battisti, Elicta Architecture, 2002

First published in the USA in 1981 by Rizzoli International Publications.

Renaissance Engineers: From Brunelleschi to Leonardo da Vinci, Paolo Galluzzi, Giunti Publications, 2004.

The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World, Paul Robert Walker, Perennial-Harper Collins Publishers, 2003.