ADVENTURES IN ARCHITECTURE: THE SERIES

Il Duomo: Brunelleschi and the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore

Episode 8: The Other Side of Filippo

by Jim Atkins, FAIA, FKIA

Illustrations by Jim Anderson

Summary: In our last episode, Filippo Brunelleschi rose to the occasion by designing and constructing magnificent machines to hoist building materials to their lofty levels and move them into place to complete Il Duomo. He summoned his talents from his earlier experience as a clockmaker and his knowledge of the mechanics of wheels, gears, and motion—along with his knowledge of building materials—to produce a level of technology and efficiency that was unequaled and unsurpassed until the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s.

This feat of designing and constructing the largest masonry dome in history is quite enough by itself, but he went far beyond that with his machines, his artistry in sculpting, woodcarving, and casting bronze. He was persuasive and therefore successful, convincing the wardens of the Opera del Duomo that he could build the dome without revealing exactly how it would be done. He was a serious businessman who went about his work with intensity and resolve.

But there is another side to Filippo. Contrary to popular belief, he was not successful at everything that he set out to do, and he was not always as serious as one would expect of such a businessman. He also had a humorous side and enjoyed playing tricks. Join us as we explore the other side of this fascinating genius of the Renaissance, follow his antics as a trickster, and experience his failures at some less-than-great ideas and designs.

The egg

The story of the egg has become Renaissance folklore. The tale is told that when Filippo was meeting with the wardens to convince them he could be the capomaestro elite, they became somewhat impatient with his mysterious design representations. He did not want to tell them of the specifics of his design, but they continued to insist that he reveal to them precisely how he would build the dome.

He continued to exert his best marketing acumen to the impatient group to no avail. Realizing that the closing of the deal likely was not imminent, he excused himself and retired to the kitchen. (Work with me on this, not everyone carries an egg around in their pocket.)

He returned to the meeting and placed an egg on the stone table, and he challenged the wardens to stand the egg on its end. They looked at him quizzically, but they assumed that a man with such great talent had devised some way to accomplish this seemingly difficult task. They tried repeatedly to stand the egg up with no success. Each time it fell over and rolled across the table. Finally, in exasperation, they challenged him to do what he had demanded of them.

Filippo grasped the egg and slammed it firmly on the table, cracking the bottom, leaving a slight indention. The egg stood upright, and he stepped back from the table with a mischievous look of achievement in his eyes. The wardens reacted in surprise and indignation, protesting that they too could have done the same if they had only known how he intended to do it. Filippo rose from his chair and smiled, and he explained that they would have had the same reaction if he had revealed to them his plan for constructing the dome. Like the egg trick, they would have concluded that anyone could do it. Filippo grasped the egg and slammed it firmly on the table, cracking the bottom, leaving a slight indention. The egg stood upright, and he stepped back from the table with a mischievous look of achievement in his eyes. The wardens reacted in surprise and indignation, protesting that they too could have done the same if they had only known how he intended to do it. Filippo rose from his chair and smiled, and he explained that they would have had the same reaction if he had revealed to them his plan for constructing the dome. Like the egg trick, they would have concluded that anyone could do it.

The story goes that his egg trick won him the commission. It’s a gratifying and colorful tale, but documentation of its authenticity is somewhat limited, and such stories about legendary heroes can take a life of their own.

Manetto, il Grasso

Another, more elaborate trick hatched by Filippo involved many accomplices; its orchestration must have been exhaustive. The victim was Manetto di Jacopo, a master woodworker and acquaintance of Filippo. He was called, “Il Grasso,” the fat man, because of his girth. (These 15th-century Italians were obviously straightforward in their assessments.)

He was among Filippo’s circle of friends, and in reaction to Manetto’s failure to show up at a social event, Filippo became irritated and devised a trick on him. He enlisted his friends in a plot to convince Manetto that he was yet another man named Matteo.

After Manetto left his shop one evening, Filippo found his way in and locked the door. He completely rearranged the order of Manetto’s tools on his work bench. When Manetto returned later, he tried the door, only to hear the sound of his own voice inside. Filippo, impersonating him, ordered him to leave. The voice was so real that Manetto left in discord, only to run face-to-face into Donatello, who addressed him as the other man, Matteo. Soon after, a bailiff arrived and addressed him as Matteo, and hauled him off to the Stinche prison for not paying his debts.

The poor man spent a fretful night thinking that he was simply mistaken for another person. The next morning, the actual brothers of the real Matteo arrived at the prison to bail him out. They identified him as Matteo, and paid his fine. They conversed with him and treated him as if he were their brother. This confused him greatly. They took him to Matteo’s home over his protests. That evening Manetto became convinced that he actually was Matteo. Later, he was knocked out with a drug provided by Filippo and taken back to his home and placed on his bed with his head placed at the foot.

He awoke completely confused. Soon Matteo’s brothers arrived and addressed him using his actual name, Manetto. They explained how their brother, on the last evening thought himself to be someone else. This confused him all the more. The ruse ultimately was confirmed by none other than Matteo himself, who arrived and described his mysterious dream of being a woodworker, like Manetto. With that, Manetto surrendered completely, and he was convinced that he had temporarily exchanged identities with Matteo.

This interesting exchange of reality and fantasy was not unlike Brunelleschi’s perspective machine that we explored in Episode 3. Much like the viewer of that machine, who could not discern between reality and the painted canvas, Manetto could not discern between reality and the ruse. Such seemingly frivolous acts committed by Brunelleschi reveal to us the true nature of his genius.

Fortunately, this story has a good ending. Manetto was so humiliated that he left Italy for Hungary, where he became successful with his work and made a great deal of money. Filippo would later claim that it was his trick that made Manetto successful by driving him out of Italy. (Our man Filippo was a shameless opportunist as well as a trickster.)

The archrival Ghiberti

Throughout this series, we have addressed the great rivalry between Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo. The riff began when they were both awarded the commission for the doors of the Baptistery of St Giovanni and was exacerbated by the same outcome on Il Duomo. Filippo thought himself to be the sole great artisan of Tuscany with no recognizable competition, and he considered the ultimate insult to be named a co-capomaestro with Lorenzo on the dome and receive the same fee for professional services. (Something tells me that Filippo would not be a viable candidate for integrated project delivery.)

As we observed in an earlier episode, there was but only one wooden tension ring placed in the dome; as the remaining ones were of sandstone. This was likely because of the limited supply of trees available in Tuscany. As the time approached to construct the wooden ring, our man Filippo hatched a plan for dealing with his lifelong adversary, Lorenzo. As we observed in an earlier episode, there was but only one wooden tension ring placed in the dome; as the remaining ones were of sandstone. This was likely because of the limited supply of trees available in Tuscany. As the time approached to construct the wooden ring, our man Filippo hatched a plan for dealing with his lifelong adversary, Lorenzo.

When it came time to build the wooden ring, Filippo suddenly fell ill and was forced to his bed. His condition was acknowledged as grave, and his survival was reported as uncertain. It fell upon Lorenzo to design and build the ring. He set about the work, not knowing Filippo’s design intentions, but he moved ahead nonetheless with his best skill and effort.

After portions of Lorenzo’s wooden ring had been put into place, Filippo made a miraculous recovery and reappeared on the job site. He ridiculed and condemned the work of Lorenzo, demanding that the ill-conceived design be removed and replaced. By this time Filippo’s credibility was unchallengeable, and Lorenzo’s work was torn out and replaced with Filippo’s own design. Lorenzo was put in disgrace and left the site, never again to spend much time on the dome. After the many years of sparring, Filippo had finally won out over his archrival … or so he thought.

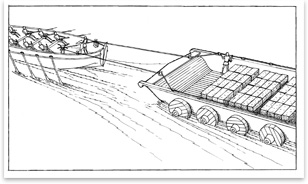

Il Badalone and the Arno

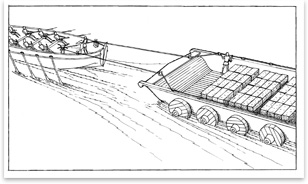

A fascinating but not always successful aspect of our profession is the tendency of architects to venture into other businesses, and Filippo was no exception. The white marble from Carrera was plentiful, but the cost of shipping it by land or down the tempestuous Arno River was cost prohibitive; so much so that the wardens had desperately resorted to using new stockpiled tombstones, already available in Florence, to avoid paying the exorbitant premium for shipping.

Our industrious Filippo had an idea to transport the stone at half the going rate using his inventive skills, and still make money. He designed a flat, raft-like boat with seven wooden wheels on each side. The intention was to load the structure with marble at the quarry, and move it by land to the Arno. There it would be floated down the river using other boats to pull and guide it. The boat’s appearance was quite unique, and it was dubbed “Il Badalone,” the monster.

As the story goes, things went well on the trip to the Arno, and the boat floated its weighty cargo successfully. However, troubles arose somewhere down river on the way to Florence, and the boat capsized. The stone was lost to the bottom of the river. It cost Filippo a good sum, and although he made numerous attempts to recover the lost goods, he was never able to do so. As the story goes, things went well on the trip to the Arno, and the boat floated its weighty cargo successfully. However, troubles arose somewhere down river on the way to Florence, and the boat capsized. The stone was lost to the bottom of the river. It cost Filippo a good sum, and although he made numerous attempts to recover the lost goods, he was never able to do so.

Luck runs out at Lucca

In the time of Brunelleschi, it was not uncommon for architects to be engaged by their government in the business of war. Remember that Leonardo da Vinci designed numerous war machines, including elaborate catapults and giant crossbows.

And so it was in 1430 when our man was sent into battle against the duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti, who had waged war on the Florentines. The strategic city of Lucca had been captured and occupied by the aggressor, and Filippo’s strategy was to trap the inhabitants inside the city, rendering them ineffective.

In centuries past, the city had purportedly been saved from flooding by an Irish monk named St. Frediano, who had rescued the city by controlling the wild Serchio River with earthen embankments. Filippo’s plan was to breach the protective barriers and surround the city with standing water. The occupants would have no other recourse but to surrender. On the surface, no pun intended, it certainly looked like a cool and workable plan with much liquidity.

But, in the end, Filippo’s well intended strategy was a failure. One dark night the enemy crept into the Florentine camp and breached the trench that Filippo had dug to divert the Serchio. The low areas were flooded as Filippo intended, but the embankment was collaterally destroyed and the waters rushed upon the Florentine camp, sending the army in a frantic retreat to higher ground. The next day the Florentines were defeated in the ensuing battle, and Filippo had once again failed to accomplish his objective.

Nonetheless, soon thereafter the Florentines appealed for peace with the duke of Milan, and harmony was restored. Although Filippo had suffered yet another failure in addition to the loss of his precious Carrera marble, his name was not ruined because of his widely acclaimed success as the architect of Il Duomo. I guess for some, fame is not fleeting.

Maligned by the masons

Troubles visited Filippo once again when he was arrested and thrown into prison by The Arte dei Maestri di Pietra e di Legname, the Guild of Stonemasons and Carpenters. It was one of the largest Florentine guilds and was operated more for politics than for the trades it represented. (Hmmm, I think we may be able to relate to that.) It was managed and manipulated by the wealthy families of Tuscany: the Capponi, the Medici, the Spini, the Bardi, and the Strozzi. (It looks like the i’s have it.) They were a force to be reckoned with, and they could definitely make you an offer that you could not refuse.

Meanwhile, Filippo’s arrest was not without suspicious circumstances. The overdue amount was approximately what a common laborer would earn in one day’s work. In addition, records indicate that although many other members were delinquent on their dues, none of them were arrested as was Filippo.

The plot thickens when we find that none other than Lorenzo Ghiberti was guilty of the same charge but never arrested. Interestingly, he was not only a member of the guild, but he was a mover and shaker within the organization, serving as consul and associating with the “higher ups.” (Touché, nes pas?)

The wardens of the Opera came to Filippo’s aid after almost two weeks in confinement. There has to be something sinister at work here, because even Manetto received better treatment than this. Filippo was released, and the next day a pro-Medici government was elected to power, and his headaches and misfortunes were finally put to rest … or so he thought.

The pickpocket protégé

Filippo had become acquainted with a boy, Andrea Cavalcanti, known as Il Buggiano, 15 years previous. He employed him on many projects, and his skills as a sculptor were widely celebrated. He became a master in the Silk Guild at 21 years old, much like Filippo, and through his hard work Buggiano became an apprentice to our man. Filippo liked the boy, who became the son that he never had.

Buggiano’s skills were remarkable, and he occasionally surpassed Filippo in his accomplishments. Filippo had agreed to pay him 200 Florins per year for his work on the cathedrals of Santa Maria del Fiore and San Lorenzo. However, it is reported that Filippo, who was known to be sloppy at his bookkeeping, did not honor the agreement.

Buggiano, consistent with the unruly youth of his time, took Filippo’s money and jewels and hightailed it to Naples. Filippo was no doubt shocked and disappointed. For Filippo, the 200 Florins was a pittance, based on his earning ability, and it is interesting that he created the problem by neglecting to pay the boy as he did.

Filippo worked within the system and appealed to his eminence Pope Eugenius IV, making the affair an international event. The papacy requested that Queen Giovanna of Naples return the boy with his booty, and soon thereafter Buggiano was delivered back to Florence and into Filippo’s guardianship. The young man dutifully resumed his assigned tasks and all returned to normal. Filippo did not seek retribution, possibly because he could see himself in the feisty young man, and soon thereafter he officially named Buggiano as his sole heir.

Conclusion

Filippo Brunelleschi typically is viewed as the great architect of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, a serious man of wisdom and will, who worked hard and enjoyed the fruits of his extraordinary talents and labor. But as we have seen, he had another side, one of jokes and trickery, and his successes were not the whole of his life. The value that we must take from Brunelleschi is that in spite of his successes, he was an ordinary person with ordinary experiences. Although he accomplished great things and ascended to a great position in the history of architecture, life came at him the same way it comes at the rest of us. Perhaps it was this mixed bag that made him what he was.

We must realize that similar outcomes are available to every one of us, perhaps on a different scale. Life presents opportunities, challenges, failures, and sometimes a pinch of luck, and if we live our lives as did Filippo, fully engaged with the throttle down, yet resilient and unwavering in our quests, we may just achieve our own Il Duomo.

|

As we observed in an earlier episode, there was but only one wooden tension ring placed in the dome; as the remaining ones were of sandstone. This was likely because of the limited supply of trees available in Tuscany. As the time approached to construct the wooden ring, our man Filippo hatched a plan for dealing with his lifelong adversary, Lorenzo.

As we observed in an earlier episode, there was but only one wooden tension ring placed in the dome; as the remaining ones were of sandstone. This was likely because of the limited supply of trees available in Tuscany. As the time approached to construct the wooden ring, our man Filippo hatched a plan for dealing with his lifelong adversary, Lorenzo. As the story goes, things went well on the trip to the Arno, and the boat floated its weighty cargo successfully. However, troubles arose somewhere down river on the way to Florence, and the boat capsized. The stone was lost to the bottom of the river. It cost Filippo a good sum, and although he made numerous attempts to recover the lost goods, he was never able to do so.

As the story goes, things went well on the trip to the Arno, and the boat floated its weighty cargo successfully. However, troubles arose somewhere down river on the way to Florence, and the boat capsized. The stone was lost to the bottom of the river. It cost Filippo a good sum, and although he made numerous attempts to recover the lost goods, he was never able to do so.