ADVENTURES IN ARCHITECTURE by Jim Atkins, FAIA, FKIA Summary: In his second installment of the design and construction of the magnificent Duomo in Florence, Jim Atkins examines the events that led to the 15th century wool merchants’ selection of Filippo Brunelleschi and Lorenzo Ghiberti as co-capomaestros in a rivalry some contend sparked the Renaissance. In our last episode, the powerful wool merchants, the Arte della Lana, called for a competition to design the dome of the partially built cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore. The cautious building committee, fearful of a structural failure, had called for enlargement of the supporting pilasters, which would make the dome the largest masonry span in the world. A dome of this size had never been constructed, and there was great debate as to how to accomplish the task. While centering armatures to support the masonry during construction and buttresses to laterally support the walls beneath the dome were proposed, the Florentines favored a cleaner design without the buttresses. But who could build such a structure? The two local favorites were Lorenzo Ghiberti, who hit it big on his “Gates of Paradise” bronze doors at the cathedral’s Baptistery, and a little known goldsmith, clockmaker, and sculptor named Filippo Brunelleschi. The winner would be named the capomaestro, known today as the architect-of-record, and would be charged with designing and overseeing construction of this monumental project. The request for proposals The medium of choice for competitions in that time was the model; a smaller version of what the finished design would be. Some models were the size of small houses, and they were erected near the cathedral to illustrate the design scope to the townspeople. Sometimes they were moved inside the cathedral itself to be kept for comparison to the finished product. It is interesting that this effective design control element, the mockup, is frequently deleted from scopes in projects today for cost savings reasons. The book, Brunelleschi’s Dome, by Ross King, provides us with an English interpretation of the request for proposal. Whoever desires to make any model or design for the vaulting of the main Dome of the Cathedral under construction by the Opera del Duomo—for armature, scaffold, or other thing, or any lifting device pertaining to the construction and perfecting of said cupola or vault—shall do so before the end of the month of September. If the model be used he shall be entitled to a payment of 200 gold Florins.

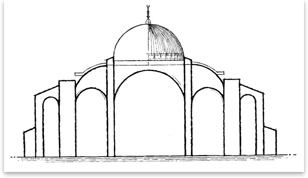

These clients also realized that other supplementary devices would be required to reach substantial completion, such as machines, scaffolding, or hoisting cranes. The RFP acknowledged that more than a design would be needed to build the dome. Scaffolding hoists and masonry bracing were not available “off-the-shelf” items in the 15th century. By today’s standards this would be difficult, if not impossible, to accomplish. What does today’s average architect know about scaffolding and cranes? In fact, when this does come up these days, we typically run hard in the other direction. Heaven forbid that our structural engineer would review a submittal on a tower crane base, much less a tower crane structure. Perhaps integrated project delivery is actually returning us to the practical ideals of the Renaissance. Perhaps, once again we architects may begin to think and design beyond the four corners of the building itself. How bright is the future? It makes us older ones wish we were much younger. However, it likely has the same effect on lawyers. The dark horse Meanwhile, Filippo, whose skills were that of a goldsmith, a clockmaker, and a sculptor, was the odd man out. Who was this guy? His trade as a goldsmith was not considered mainstream to current construction technology like the master masons. In any case, hopefully his gig at clock making would help him out with his model building. He would be up against many designers, some from cities outside Florence such as Pisa and Siena. It is reported that there were 12 competitors who submitted 17 models. At least one submission included a model for a hoisting device. Each participant had six weeks to complete their work. Such submissions could consist of physical models, drawn designs, or only stated recommendations as to how this great feat might be accomplished. Models were definitely the preferred medium in that they could communicate spatial solutions as well as overall design. The design was expected to solve many challenges, such as how the masonry would be held in place and how the tons of materials could be raised to the lofty elevation of the dome. Hoisting machines were rare and very limited in capacity at that time, and the wardens apparently recognized that solutions beyond architecture would be required to complete the project. How will our man fare in the competition? It looks like clock-making and sculpting alone may not be enough to get him by. Maybe his digging around in the Roman ruins has given him some design savvy. The plot thickens It seems that the Opera was quite fascinated by Filippo’s proposal to omit the centering armature during construction; a revolutionary approach that many thought could not be done. And if the buttresses could be eliminated through the use of the tension rings, Opera del Duomo and the people of Florence would be happy. The buttressed dome like the Basilica of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople was a design that the Florentines wanted to avoid.

No winner was announced, and two meetings were held in December of 1418 for the competitors to “demonstrate and defend” their designs. Nothing was decided in these meetings or in all of the following year, 1419. Apparently public project development schedules could be as glacial back then as they can be today. Down to the wire They were both named winners in that competition, but Brunelleschi doggedly refused to accept a position on the project equal to Ghiberti. He declined the commission and withdrew. To say that Filippo had a strong will obviously is an understatement.

In July 1419, Filippo was paid for a model of a proposed lantern that he had built to place on top of his model of the cupola. Early in 1420, he provided wire and string to demonstrate how he had measured his work on the dome. The hoops that an architect had to jump through back then to win a competition were apparently as daunting as they are today. May I have the envelope, please? Filippo protested the election of Lorenzo and again refused the commission, but he was dissuaded from quitting by his supporters. The gold florins may have also been a factor. He may have been a self-centered artist, but he certainly wasn’t an idiot. Although the two masters were declared equal in status on the project, their salaries at 36 Florins each per year were less than that paid in the past. Does this sound like a familiar experience? Filippo’s salary would eventually increase over Lorenzo’s, but never his designated status on the project. Nonetheless, they both proceeded with the work, apparently with the hatchet buried handle up. Other shenanigans would arise between them in future encounters—as the work on the dome progressed, they would spar and joust time and again on many other issues. Brunelleschi was a phenomenal architect who arrived on the scene in Florence at just the right time. Who knows what would have become of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore if he had not appeared with his innovation and unsurpassed talent. Perhaps it would be viewed today as just another buttressed cathedral among those scattered across Europe. Or perhaps it may have joined the ranks of great projects in history never completed. As the dome construction progressed, many innovations for the dome design and its construction would be required. The solutions brought by Brunelleschi were not only original; they went beyond the limits of existing design and technology. This incredible man, although physically small in stature, would become a giant among the greatest designers and inventors of all time. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

Read the first installment of “Il Duomo: Brunelleschi and the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore”

Next Month

Join us next month when we celebrate the many talents of Filippo Brunelleschi, architect, goldsmith, clockmaker, and sculptor. His designs, artistry, and inventions reach far beyond the building of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore.

His designs for machinery to build the dome were unprecedented, and later a young apprentice, Leonardo da Vinci, would study and draw them in his aspirations to do what the great Brunelleschi had done. Yet Filippo’s technical understanding and expertise were merely a supplement to his innovative design talents.

Although his big hit is viewed as Il Duomo, Filippo’s contributions to architecture and building technology were a major catalyst in the Renaissance. So be sure not to miss episode 3, A Man of Many Talents, when we examine the brains behind the bang; a look inside the incredible Filipo Brunelleschi.

Until next time, good luck out there.

—JA

Photos

All photos courtesy of the author.

1. Gold florin—Florence, Italy, 1252-1422.

2 The buttressed dome of Hagia Sophia.

3. The Baptistery Doors at Santa Maria del Fiore.

References and further reading

Brunelleschi: Studies of His Technology and Inventions, Frank D. Prager and Gustina

+-Scaglia, Dover Publications, 1970

Brunelleschi’s Cupola: Past and Present of an Architectural Masterpiece, Giovanni Fanelli and Michele Fanelli, Mandragora, 2004

Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture, Ross King, Penguin Books, 2000

Filppo Brunelleschi, Engenio Battisti, Elicta Architecture, 2002

First published in the USA in 1981 by Rizzoli International Publications

Renaissance Engineers: From Brunelleschi to Leonardo da Vinci, Paolo Galluzzi, Giunti Publications, 2004

The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World, Paul Robert Walker, Perennial-Harper Collins Publishers, 2003

Jim Atkins is a principal with HKS Architects in Dallas where he is involved with project management, construction services and risk management. Occasionally he hangs out in European basilicas.