| ADVENTURES IN ARCHITECTURE: IL DUOMO Il Duomo: Brunelleschi and the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore

Ultimately, it is a story of triumph, and the end result is an architectural wonder; a classic monument to innovation, invention, perseverance, and dogged determination. It is a story that we architects desperately need as we turn on the lights, crank up the coffee pot, and check on the status of our projects, day after day. This article is the first in a monthly series for 2008. Each month over the coming year we will return to the 15th century and join Filippo Brunelleschi in his quest to design and build Il Duomo, the magnificent dome of Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore. We will follow Filippo as he starts out as a goldsmith and sculptor, his explorations in the ancient ruins of Rome, which gave him insight into dome construction, and his successful bid to become a capomaestro, the Renaissance equivalent to the architect of record. We will follow him as he solves the challenges of masonry constructed without centering, something never before accomplished at this scale. We will observe his development of herringbone-patterned masonry, which effectively transfers loads, allowing the dome to be completed. And we will explore the intricate machines he invented and constructed to hoist and move heavy materials during construction. He truly was a Master Builder.

He was truly a Renaissance man in that he assumed every role necessary to get the job done, a feat that if pursued today would surely send our insurance agent into cardiac arrest. So settle in for the first episode in this exciting series. You will be amazed at how little the bumps in the road of architecture have changed in the past six centuries. Don’t miss an episode, and you are guaranteed to have a real adventure in architecture. Monument of the Renaissance: Santa Maria del Fiore

Arnolfo had died only six years after construction of the cathedral had begun, and for the next 30 years work almost came to a halt. In 1331 the powerful Arte della Lana, the Guild of Wool Merchants, took over control of operations and put the architect, Giotto, in charge. He would design and build the bell tower. Unions had money and power way back then, and in 14th century Florence the Wool Merchants became the client on the cathedral. They called all the shots. They were the wealthiest and most powerful guild in Europe; bigger than Jimmy Hoffa.

Il Duomo Nonetheless, a final design began to evolve in 1366 when the wardens of the Opera, the committee administering the work for the Wool Merchants, ordered the current capomaestro, Giovanni di Lapo Ghini, to build a model of the dome.

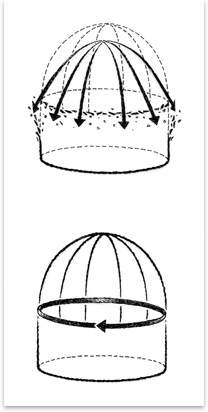

Giovanni stayed with the Gothic approach with buttresses supporting the drum beneath the dome. Neri, on the other hand, proposed a different design. He proposed that the dome be constructed with tension rings, or chains, that would resist the outward pressures created at the base of the dome, holding the span together like steel hoops hold together the staves of a wooden barrel. It is interesting that Brunelleschi receives much credit for coming up with the tension ring concept, although he only oversaw their construction. The tension rings were proposed by Neri before Filippo got involved. It affirms the benefits of good public relations and benevolent historians. The rings would be contained within the walls and thus not visible like the flying buttresses used in Germany and France, a design element that was neither admired nor politically supported by the Florentines. But such a radical design had no precedent, and debate raged among the townspeople and within the Opera del Duomo as to its constructability. Interestingly, the wardens of the Opera del Duomo eventually chose Neri’s proposal even though the uncertainties of structural design in that day led to great concern. In that time there were many instances of buildings that leaned and some that collapsed entirely. The campanile in neighboring Pisa is the most famous example.

Can you imagine receiving a commission for a project with a scope that surpassed all known design and technology? This truly was the greatest accomplishment of the Renaissance, yet such a venture would not have a chance of happening in today’s industry, systemic with lawyers and insurance policy requirements. One message that we must take from this accomplishment is that anything is possible if you have the courage, you have the talent, and you can get the public to support you. Innovazione

Perhaps architects today should be required to study the construction of renowned projects as well as their design details and characteristics. If this should happen, perhaps we would experience more projects at the profound level of Brunelleschi. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Jim Atkins is a principal with HKS Architects in Dallas, where he is involved with project management, construction services, and risk management.

Illustrations

(All photos courtesy of the author.)

1. Santa Maria del Fiore

2. The Arno River

3. Florence today as seen from Il Duomo

4. The Bell Tower of Santa Maria del Fiore

5. Top, without tension ring; bottom, with tension ring

6. The bell tower at Pisa

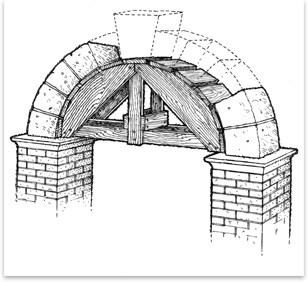

7. Centering used for a stone arch.

Next Month

Ed. note: Look for future installments of “Adventures in Architecture” in the Practice Section of AIArchitect on the fourth Friday of the month.

Join us next month when we experience the excitement of the dome design competition. Who will win the money and the commission? The tidy sum of two hundred florins was the prize for the successful design. I’m not certain of the exchange rate, but with the dollar going in the toilet, it has to be big bucks by today’s standards. Here’s a tantalizing hint about the coming episode. Someone else is named capomaestro.

Settle in for an exciting year as we journey through the 15th century with Filippo Bruneleschi, experiencing his ups and downs and celebrating his successes. The story is ripe with excitement and drama; rivals, competition, villains and travails, it is every bit as dramatic and treacherous as architecture is today. Let’s face it; things just haven’t changed all that much over the past six centuries. At least today you’re not riding to work on some fuzzy animal in the dead of winter.

So hang on to your Blackberry because this story follows a colorful and fascinating path. You will not want to miss a single episode. It is a true adventure in architecture.

Until next time, good luck out there.

—JA

Further Reading

• Brunelleschi: Studies of His Technology and Inventions, Frank D. Prager and Gustina Scaglia, Dover Publications, 1970

• Brunelleschi’s Cupola: Past and Present of an Architectural Masterpiece, Giovanni Fanelli and Michele Fanelli, Mandragora, 2004

• Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture, Ross King, Penguin Books, 2000

• Filippo Bruneleschi, Engenio Battisti, Elicta Architecture, 2002

• First published in the USA in 1981 by Rizzoli International Publications

• Renaissance Engineers: From Brunelleschi to Leonardo da Vinci, Paolo Galluzzi, Giunti Publications, 2004

• The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World, Paul Robert Walker, Perennial-Harper Collins Publishers, 2003.