| David Jameson: Designing In Between the Lines A designer sets the table, their buildings create the spaces

David Jameson, FAIA. Images courtesy of David Jameson Architect. Summary: The architecture of David Jameson, FAIA, uses kaleidoscopic views, orientations, and materials to form revelatory residential experiences. This experiential Modernism is conceptually extroverted and bold, twisting and elevating pavilions and planes into witty turns of view to create fresh notions of residential placemaking.

Jameson’s House on Hoopers Island. Images courtesy of Paul Warchol. But, Jameson’s design sensibility is humble, unassuming, and grounded in Maryland’s rural Eastern Shore where he grew up. He’s been influenced by the vernacular stick-framed barns and houses that make up this stretch of mid-Atlantic coastline, carefully examining the relationship of forms and the peculiar in-between spaces that happen when a barn joins a house, and a garage, and a shed, and an improvised, agrarian village is created despite itself. In his own work, Jameson designs buildings that then assume their own agency in forming unique relationships with various levels, elevations, and volumes via inspiring interstitial spaces. To this day Jameson is a local, primarily residential architect, practicing largely in the Washington, DC, area and basing his firm in Alexandria, Va. But his ideas about the joy of multifaceted building perspectives and his willingness to pay design modernity its due have given him room to expand. He’s currently working on a 15,000 to 20,000-square-foot multi-unit residential project in Woodside, Calif., that hides unexpected and enigmatic spaces within asymmetrical and orthogonal planes of varying materiality; each nook and cranny planned and executed as a wholly lyrical expression.

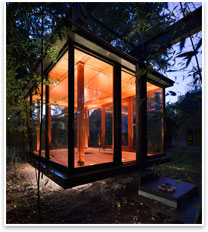

The Tea House, designed by David Jameson. Images courtesy of Paul Warchol. Earlier this month, Jameson stopped by the National Building Museum to present his firm’s work for the museum’s Spotlight on Design lecture series. AIArchitect: In many of your houses, you’ve used a pavilion-in-a-landscape motif. Your House on Hoopers Island is an example, and there are others. This concept has obsessed Modern architects for a long time, going back to Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion, and even further. What’s your attraction to this concept, and why has it been so endlessly fascinating for Modernists? Jameson: Architects for centuries have placed value on the singular gem-in-a-landscape building. If we focus on the Hooper’s Island example, what is interesting to me is that most buildings don’t have this notion of reflectivity, meaning that the conditioning of the interior and the exterior provide a reading for one another. Frank Gehry’s work, as an example, doesn’t subscribe to that notion at all. The outside can be whatever it wants and the inside is something completely different.

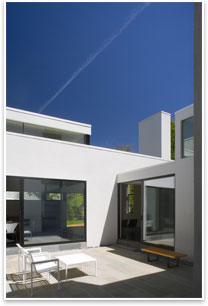

The Glenbrook Residence. Images courtesy of Paul Warchol. Growing up on the Eastern Shore, I always thought there was no architecture [there]. Even through architecture school, I kept thinking, “These are simple, unadorned, little buildings in the landscape, but they’re not architectural in the sense that they’re iconic buildings like the Farnsworth House might be.” As you [grow] up, you get influenced by the in-between spaces that exist between these simple agrarian structures. The Hoopers Island House is not so much about the idyllic pavilion in the landscape in the way the Farnsworth house is, or Philip Johnson’s Glass House. But Hooper’s Island and any of the other projects really begin to explore this notion of in-between space. The space between the four metal tube buildings and the plinths—that creates a language in a Modernist idiom that recalls the agrarian farm structures that dot the landscape. [In the] the Tea House project, that’s a pavilion in the landscape, but yet it still explores this notion of in-between reflectivity, where the conditioning of the inside and outside of the Tea House are singular—they’re one and the same. Yet, these steel wickets [elevate and frame the house] with a tectonic structure that allows the condition of the in-between space to exist. Do you see this as a subversion of the grand tradition of the Modernist pavilion-in-a-landscape? Yeah, I think so. I would hope that the space created by the building is of equal importance to the buildings themselves. Your approach to designing interstitial, in-between spaces reminds me of a conversation I had with an architect that was designing an urban neighborhood masterplan. This architect planned the neighborhood with lots of flexible, unprogrammed interstitial spaces that could be activated by entrepreneurial and artisanal activities: open storefronts, space for retail stalls, diverse uses. The idea was to create in-between places where residents could come in and let the neighborhood grow and evolve in any direction they cared to take it. This was the best way to ensure an organically urban and inviting mixed-use plan, and a warm, or even “homey” fine-grained urban fabric. Does this urban-scale idea also apply to how you think of interstitial spaces in residential projects?

Jameson’s BlackWhite Residence. Images courtesy of Paul Warchol. I would say that the interstitial space is thought of as a negative space that can be activated by its occupant at one level. On the second level, [in most buildings] you cannot go to any one window and experience any other part of the building. In the work, what I’m interested in is--is it possible to begin to create this reading of reflectivity where the condition of the internal space and the external space are quite similar so you can be in an inside space looking outside [and] back inside again, and you start to experience the building in many different ways? The BlackWhite House is an example. You can be in a virtually any one of the four lenses of the landscape on the second floor and experience the other lenses. It allows people to begin to see the markings and making of place that their dwelling is creating. And so, rather than leaving it as sort of unprogrammed, unactivated space that happenstance can occur in, it’s more of an idea of curated space where one can be inside or outside and experience the building at multiple levels. You’re a local guy. Do you ever spend much time thinking about what a contemporary residential design identity for Washington, DC might be? Generally, it’s horrific. Well, the row houses are nice.

The Jigsaw Residence. Images courtesy of Nic Lehoux. The second you get out of Dupont Circle or Logan Circle and you get away from the blocks of space-in-between-space-defining buildings, the worse and worse the housing gets. It’s interesting to me that most housing is so bad. There’s a sporadic interesting house, but more often than not there are these puffy foam houses that are synthetic replicas of a bygone era. Unfortunately, they’re not authentic. What’s wrong with the good in-town housing is that there is a group of people that live in those houses that don’t want them to change. They want any addition to their 1880s row house to look like it was built in 1880. It’s better to basically say, “Let’s have this Modernist intervention project attached to this 1880s row house and allow it to be like London, where there’s this sort of stepping vocabulary of time.” The problem with historic preservation in a lot of the Eastern U.S. cities is that they’re still too young of a city to have garnered many iterations of style. If you go to places like Prague or London, those cities are so old it’s natural that over time infill buildings are from 100 years later or 200 years later. So in places like that you’re already preserving things that were built in a wider spectrum of time? Right. You’re looking at a much broader spectrum of building typology, whereas in America, the building typology is such a narrow slice of what’s built. If you could take on any project—any type, any size—what would it be? I’m hoping that I can take the ground we’ve tread in the last five to six years and take these ideas and scale them into museum projects or institutional projects. I’d like to be able to do more work that more people can experience. |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Jeanne Gang: Material Humanist

› Amidst a Swirl of Extremes, Weiss/Manfredi’s Architecture Emerges of Accomplish the Impossible

› Sun, Soil, Spirit: The Architecture of Mario Botta

› Bing Thom on Building Urbanism with a Light Touch

› Against Interpretation

› Tudor Place: Democracy Starts at Home

› KieranTimberlake Moves Pre-Fab into Mass Customization

› Kowalewski Residence: Three Views of a Family

See what the Committee on Design Knowledge Community is up to.

See what the Housing and Custom Residential Knowledge Community is up to.

Visit the National Building Museum’s Web site.

Do you know the Architect’s Knowledge Resource?

The AIA’s resource knowledge base can connect you to the AIA Best Practices article “Public Relations for Residential Architects.”

See what else the Architects Knowledge Resource has to offer for your practice.

From the AIA Bookstore: Modern Sustainable Residential Design by William Carpenter, FAIA, (John Wiley and Sons, 2009)