Sun, Soil, Spirit: The Architecture of Mario Botta

The Swiss Modernist speaks of architecture’s role in a confused and commodified age

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

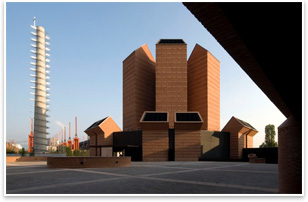

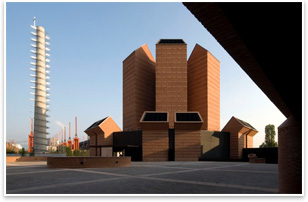

Summary: Mario Botta, Hon. FAIA, is a Modernist master of earthen fabric, still sculpting timeless yet temporary engaged elemental spaces out of brick and stoneware while his contemporaries rely on the materials of now to define the condition of now. He’s worked mostly in Europe, but in the U.S. his best known building is the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and his Bechtler Museum of Modern Art in Charlotte is currently under construction. Born in Mendrisio, Switzerland, but effusively Italian in manner and culture, his calling is to confront the existential crisis of the contemporary built environment through the clear orientation of space and the humanistic affirmation of man’s inherent uniqueness. On one side, the banal, the commodified, the common; on the other, the authentic, the singular, the sacred. Summary: Mario Botta, Hon. FAIA, is a Modernist master of earthen fabric, still sculpting timeless yet temporary engaged elemental spaces out of brick and stoneware while his contemporaries rely on the materials of now to define the condition of now. He’s worked mostly in Europe, but in the U.S. his best known building is the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and his Bechtler Museum of Modern Art in Charlotte is currently under construction. Born in Mendrisio, Switzerland, but effusively Italian in manner and culture, his calling is to confront the existential crisis of the contemporary built environment through the clear orientation of space and the humanistic affirmation of man’s inherent uniqueness. On one side, the banal, the commodified, the common; on the other, the authentic, the singular, the sacred.

Botta (who spoke through a translator), came to Washington on April 29 to give a lecture for the National Building Museum’s Spotlight on Design series. He also sat down with AIArchitect’s Associate Editor Zach Mortice. Botta (who spoke through a translator), came to Washington on April 29 to give a lecture for the National Building Museum’s Spotlight on Design series. He also sat down with AIArchitect’s Associate Editor Zach Mortice.

AIArchitect: Let’s talk about your long and productive relationship with brick as a building material. How has this grown into such an integral part of your work?

Mario Botta: First of all, brick is a natural product. It’s the product of soil and sun, and I really like to think I’m building something [as a] natural product, whether it’s brick or stone.

It’s a rather cheap, reasonable-costing material, and it also has a very interesting module. In other words, it can be hand-held. It’s also an interesting material because it gives you the ability to produce different textures. Like in [my] museum in San Francisco, you can see how brick was used in the ‘30s [in adjacent buildings], and how it’s been used here.

AIArchitect: When you speak of brick as being a product of sun and soil, it’s a very elemental way to talk about building materials, and it reminds me of how Louis Kahn spoke about building. Is this something you absorbed from him while you were under his tutelage? AIArchitect: When you speak of brick as being a product of sun and soil, it’s a very elemental way to talk about building materials, and it reminds me of how Louis Kahn spoke about building. Is this something you absorbed from him while you were under his tutelage?

Mario Botta: Yes, absolutely. He said a brick aspires to become an arch, because there is gravity and weight, and so if a brick becomes an arch, it will unload the weight.

AIArchitect: You’ve designed many religious spaces in your career, and this is a building type that exists across all cultures and faiths. In this context, how has your approach to designing spiritual spaces evolved over the years?

Mario Botta: I believe that to project and plan a sacred space is one of the most interesting tasks of an architect, and this is because architecture conveys the idea of [sacredness]. The first gesture of an architect is to draw a perimeter; in other words, to separate the microclimate from the macro space outside. This in itself is a sacred act. Architecture in itself conveys this idea of limiting space. It’s a limit between the finite and the infinite. From this point of view, all architecture is sacred.

AIArchitect: Your religious buildings tend to not embrace any specific faith’s iconography and symbols. They’re abstract expressions. Do you think you could ever do a religious building that did use these kinds of explicit icons and tropes? AIArchitect: Your religious buildings tend to not embrace any specific faith’s iconography and symbols. They’re abstract expressions. Do you think you could ever do a religious building that did use these kinds of explicit icons and tropes?

Mario Botta: I think I would have a problem with doing that. I believe that spirituality is universal. Of course, every religion and every liturgy has its own way of thinking, but I think we’re all men of globalization, and we have to go beyond this limit. I am designing a church right now where there will be up in the roof an opening which has the shape of a cross, but then the light of the cross will be brought down inside the building in the black space and transform the space. So in a way, yes, I have a reference of a cross, but I am changing it because I’m doing an experiment [where] I’m changing the shape inside with the black space. I want to transform this spirit in architectonic space.

AIArchitect: You’ve often spoken of how architecture is more of an ethical concern than an aesthetic concern, and that an architect’s role should be to resist the loss of identity and banalization in contemporary life caused by obsessions with consumerism. Have you ever thought there might be ways for architecture to co-opt consumerism and work with it constructively? Rem Koolhaas seems to have made himself a very successful career out of doing just this.

Mario Botta: First of all, I’m not against globalization or against a society of consumption. I am against the banalization that this society makes of this space. I hate to go into supermarkets. When you go into a supermarket, it’s like a fair of banality. Everything is false. Everything is a pretension, as if it’s beautiful or authentic. I believe space is a component that is too strong to be set aside in this battle in order to achieve a good quality of life. A better quality of life has to go through a better quality of space. That’s why I dislike it that everyday people [live] in this banal place where nothing is beautiful, [and] all of this is trying to portray a false wealth, a false richness.

AIArchitect: So do you think it’s possible to uplift and improve the building types that so often are abused and then abuse us? Supermarkets, shopping malls, office buildings—do they have hope? AIArchitect: So do you think it’s possible to uplift and improve the building types that so often are abused and then abuse us? Supermarkets, shopping malls, office buildings—do they have hope?

Mario Botta: If I look at the spaces of today, [like] supermarkets, objectively I find them ugly. Maybe the people who go there to shop feel happy because they feel like protagonists, but I can’t bring myself to say they are beautiful.

I know that today my position is in the minority, but even if it is in the minority, if there’s truth there, we have to pursue it. Who knows? Maybe tomorrow it will bloom into a renaissance.

AIArchitect: So you feel that certain building types simply can’t help us become more human?

Mario Botta: That’s right.

AIArchitect: I’ve heard critics (namely the Washington Post’s Philip Kennicott) call these consumerist-oriented building types the “architecture of distraction.” They’re myopically focused on program and circulation; pushing people though their spaces in order to entice consumerism by extracting money.

Mario Botta: I condemn them completely. At the end of the day, even though the act of consuming has its own pleasures, it still is a very poor outcome.

We have to come to a reasoned critique of the spaces of today. Heidegger said that man lives when he has the ability to orient himself in space. So he lives when he controls the space, when he knows his position, and this happens unconsciously, [like] when we go on top of a mountain we control [everything below us], or when you find yourself along a straight road, or when you face a temple. We have to come to a reasoned critique of the spaces of today. Heidegger said that man lives when he has the ability to orient himself in space. So he lives when he controls the space, when he knows his position, and this happens unconsciously, [like] when we go on top of a mountain we control [everything below us], or when you find yourself along a straight road, or when you face a temple.

That’s why I joined a choir of criticism of modern space, because what happens now is that they create a labyrinth where men are lost. They don’t know where they are anymore. They only know where they have to go because maybe there is an arrow or sign that [tells them]. Man is deprived of his natural sentiments. He does not know anymore where he finds himself, where the level of the land is, where the sky is, where anything is.

The problem is that we’re in a globalized society, so what is very important today is the search for identity. This search for identity goes through this need to belong to a place, not only from a geographical point of view, but also from the historical point of view, and in memory.

AIArchitect: What are some of your latest projects? What are you working on these days?

Mario Botta: I’m working on churches. I’ve also designed a mosque. I’m designing libraries—one at the University of Trento in Italy. I’m working on 20 different projects.

AIArchitect: And probably spending too much time in disorienting airports.

Mario Botta: That’s true. |

Summary:

Summary:

AIArchitect:

AIArchitect:

AIArchitect:

AIArchitect: