Against

Interpretation

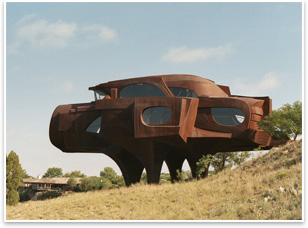

Robert Bruno’s house of welded

steel conjures up many meanings, but it arose without any of them

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: The

steel house artist and sculptor Robert Bruno has created is a non-conceptual

piece wholly informed by Bruno’s own aesthetic choices and

direction. Its spontaneous, unplanned complexity hints at the future,

the past, and (according to Bruno) calls to attention the scalar

distortion and prevalence of conceptual rhetoric in modern architecture. Summary: The

steel house artist and sculptor Robert Bruno has created is a non-conceptual

piece wholly informed by Bruno’s own aesthetic choices and

direction. Its spontaneous, unplanned complexity hints at the future,

the past, and (according to Bruno) calls to attention the scalar

distortion and prevalence of conceptual rhetoric in modern architecture.

How do you .

. . create singular, personal architecture from a non-conceptual

basis?

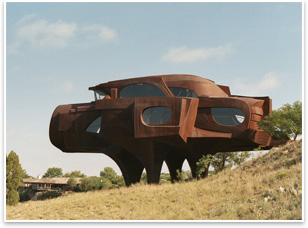

For 33 years, Robert Bruno has meticulously designed and built his

welded steel house on the edge of a canyon outside of Lubbock, Tex.

But, somehow, he’s not sure how many square feet it is (his

guess is 2,700) and he can’t explain the influences that have

informed his design over these three decades—despite the fact

that the house’s otherworldly shape seems tailor-made for free

association. A brief jaunt through any design-oriented mind brings

you to: an insect’s carapace, an alien spacecraft, M.C. Escher’s

hallucinogenic maze-scapes, and perhaps Deconstruction’s ongoing

War on the Rectangle. For 33 years, Robert Bruno has meticulously designed and built his

welded steel house on the edge of a canyon outside of Lubbock, Tex.

But, somehow, he’s not sure how many square feet it is (his

guess is 2,700) and he can’t explain the influences that have

informed his design over these three decades—despite the fact

that the house’s otherworldly shape seems tailor-made for free

association. A brief jaunt through any design-oriented mind brings

you to: an insect’s carapace, an alien spacecraft, M.C. Escher’s

hallucinogenic maze-scapes, and perhaps Deconstruction’s ongoing

War on the Rectangle.

But Bruno isn’t an entomologist, a science fiction writer,

or even a Koolhaas/Gehry acolyte. He’s an artist, and not a

conceptual one. “This house doesn’t deal with concept

at all,” he says. “I’m not trying to have something

re-emerge in the guise of my house.”

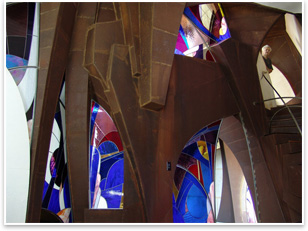

The medium is the meaning The medium is the meaning

In 1974, while teaching at the architecture school at Texas Tech

University in Lubbock, Bruno completed a large steel sculpture

just tall enough to stand under. He found this space pleasing and

decided that it might be nice to live in such a dwelling. This

humble and guileless desire is the only impetus for the design

of his richly complex house, now almost complete.

The house hitches itself to no stylistic wagons and has been spontaneously

designed and revised over the course of its 33-year construction. “What

you’re seeing is 33 years of design, not three months of design

and 33 years of labor,” Bruno says. If he would have had to

design the house in full initially and then build to this exact standard, “I

would feel as if I were working for somebody else,” he says.

This is a literal distinction for Bruno. He began the house when

he was a young man, age 29. Today he’s 62, and the majority

of his years have been spent working on the house; an open film exposure

documenting his aesthetic development and intent.

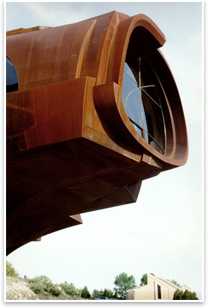

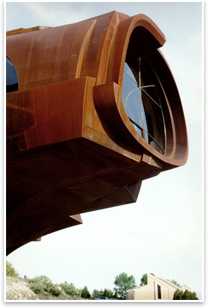

Perhaps the house’s only conceptual and planning standby is

its materiality. Instead of co-opting an external motif for the project

and building form from there, Bruno let his materials speak with

their own voice. “A lot of the shapes are helped along by the

material itself, saying, ‘This is what comes naturally,’” he

says. Naturally, it seems, Bruno’s house wants to express itself

organically, even despite steel’s reputation as a primary tool

in humankind’s arsenal of the artificial environment. Year

upon year of continual revision have evolved dense, idiosyncratic

curvatures and layerings that mimic the higher-ordered imperfections

of life. The house reveals steel to be an organic signifier not only

in form but in surface. It’s pleasingly brusque, ruddy-brown

color is only the result of rust and decay. The steel has aged with

Bruno, too.

“You just leave it out in the rain,” he says. “One

of the things that I actually like about the material is that it

does give us the sense of being another living thing that is perishable.”

The sculptor’s tools The sculptor’s tools

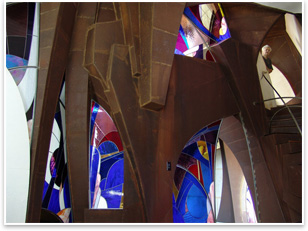

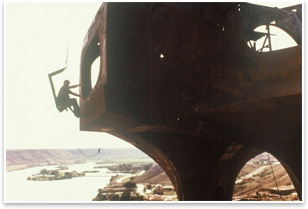

Sited on a sloping plot in the small town of Ransom Canyon, Tex.,

the house’s four legs stand it up to the top of a canyon

wall. It’s imprecisely ovoid shape is composed of a double

shell structure, an interior and exterior shell with insulation

in between. “This isn’t something draped over an interior

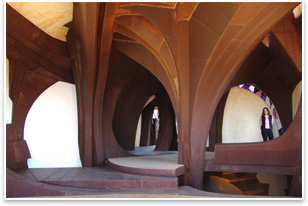

structure,” Bruno says. “The structure is the shell.” Bruno

estimates that 60 percent of the interior is made of steel, while

nearly the entire exterior is steel. The vast majority of it was

cut and welded on site and installed with simple tools: a wrench,

welder, cutting torch, c-clamps, and a cable pulley for bending

and shaping the metal.

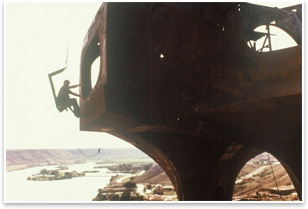

Bruno, an artist and sculptor by trade, did have to build a few

unique tools to help him in his lone quest to complete the project.

One example was a hydraulic crane that he could remotely operate

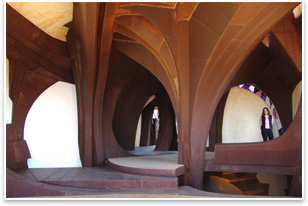

from the crane’s bucket. The room layouts and general size

of the house were the only elements Bruno planned in advanced. Spread

over three levels, the house has three bedrooms, three baths, a kitchen,

a living room, and a dining room, all of which Bruno is a few months

away from moving into.

“What it consists of . . . ”

And when he does, he says he expects the avant-garde dwelling to

be exceedingly livable. But, without the commonplace programmatic

references of furniture and interior design, those not so intimately

connected to the entity’s growth and development may not

feel the same way. Bruno’s house is delirious in its volumetric

complexity, so much so that decorative and structural elements

are nearly indistinguishable. Vertical terraces curve into stairs,

a table-like structure slopes out of the floor.

Bruno says this type of spontaneous, whimsical design is what creates

the aesthetic complexity people crave, missing from most of the built

environment around us, and largely absent from the practice of architecture

itself. “It isn’t that we’re looking for the silliness

of a maze,” he says. “We’re looking at a higher

order of complexity.” The crux of the problem: Market realities

demand that architects communicate to clients what a project will

be before it exists through imperfect, distorting mediums like models.

From this point on, Bruno says the scale is manipulated and details

are whitewashed in the transition. “Inadvertently, what ends

up happening is that the resolution at the model level is potentially

quite different from what you would resolve at full scale. I would

venture to say that almost all the large buildings we see around

us are the replica and the original is the model,” he says. Bruno says this type of spontaneous, whimsical design is what creates

the aesthetic complexity people crave, missing from most of the built

environment around us, and largely absent from the practice of architecture

itself. “It isn’t that we’re looking for the silliness

of a maze,” he says. “We’re looking at a higher

order of complexity.” The crux of the problem: Market realities

demand that architects communicate to clients what a project will

be before it exists through imperfect, distorting mediums like models.

From this point on, Bruno says the scale is manipulated and details

are whitewashed in the transition. “Inadvertently, what ends

up happening is that the resolution at the model level is potentially

quite different from what you would resolve at full scale. I would

venture to say that almost all the large buildings we see around

us are the replica and the original is the model,” he says.

The subsequently full-scaled and improvisatory details of Bruno’s

home make it feel somehow futuristic, full of components and volumes

seemingly too complex for human comprehension, yet still ancient

in its organic decomposition. It’s as if it had returned from

the future to be buried in our past, stuck here for thousands of

years.

Indeed, the house does take a stand against one temporal artistic

signifier: conceptual art. Much of art and architecture over the

past century, Bruno says, has been self-consciously concerned with

shackling itself to specific ideas and concrete themes early in

the planning process, making execution perfunctory and raw aesthetics

secondary. It’s art where, as conceptual artist Sol LeWitt

said, “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” Indeed, the house does take a stand against one temporal artistic

signifier: conceptual art. Much of art and architecture over the

past century, Bruno says, has been self-consciously concerned with

shackling itself to specific ideas and concrete themes early in

the planning process, making execution perfunctory and raw aesthetics

secondary. It’s art where, as conceptual artist Sol LeWitt

said, “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.”

Bruno uses the example of Swedish-born artist Claes Oldenburg’s

giant-sized replicas of everyday objects. His projects are easy to

discuss and imagine without ever seeing the actual object. “What

it consists of is the wall plate and light switches made big. That’s

what it is.”

Reliance on this type of design philosophy in architecture is easy to

find and easier to explain. Because architects create things using

clients’ money and the client wants to know what they’ll

be getting, architects had better find a way to explain it. All of

a sudden, a conceptual framework becomes a mandatory marketing pitch

and much of modern architecture lends itself to pithy descriptions

of what “it” is.

Examples of this can be seemingly traditional or recognizably Modern.

The National Cathedral be can easily understood as a Gothic cathedral

decorated with American history iconography, and Eero Saarinen’s

Ingalls Ice Arena at Yale doesn’t lose much in translation

when described as a an ice rink shaped like an upturned Viking ship. Examples of this can be seemingly traditional or recognizably Modern.

The National Cathedral be can easily understood as a Gothic cathedral

decorated with American history iconography, and Eero Saarinen’s

Ingalls Ice Arena at Yale doesn’t lose much in translation

when described as a an ice rink shaped like an upturned Viking ship.

Robert Bruno’s house doesn’t discuss these kinds of

worldly concerns. It speaks only to process and materiality, which

yields a summation that might read thusly: “It’s a 33-year-long

exposure of a home in steel.” |