| Jeanne Gang: Material Humanist A search for material possibilities has led her to the forefront of the architecture profession

Read Metropolis’ cover story on Jeanne Gang. See what the Committee on Design Knowledge Community is up to.

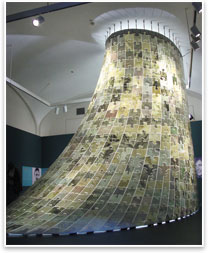

1: Jeanne Gang. Photo by Russell Boniface. 2: Zach Mortice. Photo by Russell Boniface. 3: Gang’s Marble Curtain installation at the National Building Museum. Photo by Tak Katayama. Image courtesy of Studio Gang Architects. 4. Aqua Tower. Image courtesy of Studio Gang Architects. 5. Gang’s SOS Children’s village. Photo by Steven Hall (Hedrich Blessing). Image courtesy of Studio Gang Architects. In Studio Gang’s Hyderabad Tellapur residential tower in Hyderabad, India, native residential forms and vernacular building methods are combined with new and rediscovered sustainable building practices. Her Marble Curtain installation, which most accurately articulates Studio Gang’s relentless philosophical material interrogations, approached marble with a tabula rasa mindset by hanging puzzle-cut pieces from a gallery ceiling of the National Building Museum in tension, sliced so thin they glowed translucently. Gang wanted to see what marble could become, what it could achieve with the proper effort, experimentation, and commitment, and though the subjects of her inquiry here were the possibilities of things and not people, that’s still as humanist a motive as any of the old Modernist social reformers. On March 9, Gang returned to the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., to present her firm’s work as part of their Women in Architecture lecture series. She also sat down with AIArchitect’s Associate Editor Zach Mortice. AIArchitect: You like to design public buildings. Why have you focused so much on this with your practice? Jeanne Gang: It allows the public to engage the architecture, whereas if you focus on private houses for example, it’s difficult to access a wider audience. Public buildings are like a microcosm of the city, and one of the interests in our practice is how the city works. AIArchitect: You grew up in Illinois and you’ve been proactively Midwestern in your practice in a profession that’s rather coast-centric. Is there anything in architecture now that you could call a Midwestern aesthetic or approach beyond Frank Lloyd Wright? Or is such a regional grouping forced and irrelevant? Jeanne Gang: First of all, Chicago is on a coast as well—the Lake Michigan Coast. I see ourselves as being more a part of a global community. I think the separations could be more in terms of what cities have similar climates. I see architecture getting more and more in tune with climate, and that will start to develop similarities in different parts of the world. AIArchitect: To make buildings more sustainable and collaborative with weather patterns? Jeanne Gang: Exactly. Hot, subtropical climates are going to have a set of solutions you’re not going to get in arctic areas. It could really start to be interesting if Chicago has something very much in common with someplace in Russia, for example. AIArchitect: Your Ford Calumet Environment Center is predominantly made out of locally recycled materials. How far can architects push this as a building material? Jeanne Gang: One of the biggest challenges isn’t just thinking of what’s recycled and making a building out of that. It’s rethinking the whole way projects are bid, because when you put a project out for bid, from then on it’s usually in the contractor’s hands. If you’re specifying for things to be extremely, radically local, and you’re specifying that things need to be reused, it means that architects have to insert themselves deeper into the process. Formally, I’m not as interested in buildings looking like a compilation of recycled objects, but I am very interested in making new materials out of recycled things. One of the things we’re doing in the Ford Calumet Environmental Center is making flooring out of slag, which is incredibly beautiful, but hasn’t been used before.

Jeanne Gang: We’ve done projects that are about the city and event and spectacle, and other projects that are about material experimentation. Right now we have a pair of projects that are a perfect place where those two things intersect. We’re doing a visitors center in Greenville, S.C., in the downtown and a nature interpretive center at the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains in South Carolina. Those two projects are about the spectacle of the city, and on the other hand, when visitors get upstate, they’ll be able to learn more about this incredible site: endemic species, different landscapes, natural eco-systems. They’re two projects that work together. AIArchitect: Tell me about some mentors who have influenced you. Jeanne Gang: Rem Koolhaas, founder of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture was an amazing person to work for. He was always really interesting and intellectually challenging. The way his practice was set up was a very good model for that way I set up my practice. It’s a more collaborative space. It’s not the old model of the pyramid hierarchy. When I was working at OMA, we were working a lot in teams and we worked pretty early on with structural engineers and consultants.

AIArchitect: Were there any particular trips you took with your dad that really opened up the world of design and construction for you? Jeanne Gang: One of the trips that was pretty inspiring was going out West and seeing, not really consciously engineered structures, but landscapes. I remember seeing the Grand Canyon and being overwhelmed with how much power the water had to shape this landscape. In the same trip we saw Mesa Verde; vernacular buildings carved into a cliff. There’s a tabletop cliff and the buildings were built into the side of it so they were disguised from would-be attackers. You could never see them till you got up to the edge.

Jeanne Gang: The materials are the materials of that place. This is kind of subversive in a way because people are always looking for the newest, highest-tech solution, but there are some amazing solutions that are right in front of our face that are actually very low-tech. For example, using material that’s right on the site. We’ve rediscovered that with the Hyderabad project where we’re looking at building some of the walls with a very rudimentary press so we can make bricks literally off the site. AIArchitect: Are materials a means or an end for you? Or both? Jeanne Gang: They’re a curiosity. I feel like materials all have a mystery inside them of what they haven’t yet been able to do. It takes experimentation to tease out what materials are capable of doing. The Marble Curtain project is a good example of that. It’s pretty subversive in that it’s putting stone into tension. The pulling apart of stone that we did to do that piece kind of unlocked this mystery. AIArchitect: That sounds a bit like Louis Kahn’s ruminations on the desires and philosophy of materials. Do you see this as a further exploration of his ideas? Jeanne Gang: In a way, I think it’s the opposite of what he was saying. If you ask marble what it wanted to be, the last thing it would want to do is hang from a ceiling in tension, but it is capable of doing it.

Jeanne Gang: What we’ve done is let our modern work run into the total chaos and rustic quality of construction. That might be where it starts to get that warmth, because you can actually sense that someone made this thing. |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

AIArchitect:

AIArchitect:

AIArchitect:

AIArchitect: AIArchitect:

AIArchitect: