MEMBER TO MEMBER

Amidst a Swirl of Extremes, Weiss/Manfredi’s Architecture Emerges to Accomplish the Impossible

Their work takes place somewhere between public and private, in the middle of the natural and artificial

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: Commonly known as designers who combine the disciplines of urban planning, architecture, and landscape architecture Weiss/Manfredi have never found a site they couldn’t love. The New York-based firm’s designs tuck and explode into landscapes; draw inspiration from the disappearing divisions among public, private, natural, and artificial; and look back across their sites’ histories with a multitude of interdisciplinary lenses. A contextual awareness based on the physical stock of the land defines their projects, and their buildings can never be understood without their sites—they don’t pick uncomplicated ones. Weiss/Manfredi’s architecture is given the spark of life from the friction of site conditions seemingly divided against themselves and the vision of what is and what can be. Summary: Commonly known as designers who combine the disciplines of urban planning, architecture, and landscape architecture Weiss/Manfredi have never found a site they couldn’t love. The New York-based firm’s designs tuck and explode into landscapes; draw inspiration from the disappearing divisions among public, private, natural, and artificial; and look back across their sites’ histories with a multitude of interdisciplinary lenses. A contextual awareness based on the physical stock of the land defines their projects, and their buildings can never be understood without their sites—they don’t pick uncomplicated ones. Weiss/Manfredi’s architecture is given the spark of life from the friction of site conditions seemingly divided against themselves and the vision of what is and what can be.

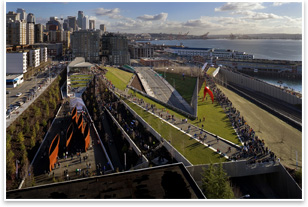

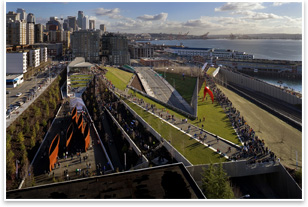

Marion Weiss, AIA, and Michael Manfredi, FAIA, came to the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., on September 15 as part of its Spotlight and Design lecture series to discuss their still-young firm’s projects, epically their Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle. They also sat down with AIArchitect Associate Editor Zach Mortice. Marion Weiss, AIA, and Michael Manfredi, FAIA, came to the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., on September 15 as part of its Spotlight and Design lecture series to discuss their still-young firm’s projects, epically their Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle. They also sat down with AIArchitect Associate Editor Zach Mortice.

AIArchitect: In your new monograph, Surface/Subsurface, you write that you’re interested in eradicating the line between public and private spaces. Is that really possible? Would anyone want to live like this? To what extent is this a hyperbolic statement?

Michael Manfredi: One shouldn’t take a statement like that at face value. Increasingly, though, distinctions between public and private are blurred. I think it’s part of our culture. We take photographs with our cell phones so that we as people become part of a public setting just as public settings become part of our own interior domestic world. We as designers need to find ways of working in that context. Otherwise, we’ll be shunted aside by other economic or political forces. So I think it requires a level of activism to believe that the public and the private realms are co-mingled, and the friction of where those two come together is really interesting.

AIArchitect: So the concept of the blurring of the public and private realms is a zeitgeist marker for you? AIArchitect: So the concept of the blurring of the public and private realms is a zeitgeist marker for you?

Michael Manfredi: It is a zeitgeist marker to the extent that it’s part of the challenges of the zeitgeist of our era. Both Marion and I feel that as designers we’ve got to really jump into that intersection between public and private.

Marion Weiss: Public and private crosses many different terrains of understanding. Our Seattle Art Museum [Olympic Sculpture Park project] is a private institution. They bought the land that was in a very public setting, and so they worked with the city, which owned the waterfront section to say: “Let’s work together”—public and private, to create something that will allow us to participate in the public realm in ways that museums never have before.

AIArchitect: Formally, how does this notion of intermingling the public and private spaces express itself in your designs?

Michael Manfredi: The Seattle Art Museum project is most emblematic of this, in the context that museums typically had been citadels of culture—on the hill, up the stairs, on the plinth. The Seattle Art Museum really took the hidden sculpture garden, which is often behind walls, and they wanted to take that idea and turn it inside out and make it part of the city.

AIArchitect: What new projects are you working on now?

Marion Weiss: We’re very excited to share that we just won the Taekwondo international competition in South Korea. It’s a cultural destination about half the size of Central Park.

Michael Manfredi: The site has a lot of topography, and, as you know from our own work, we’re interested in topography. So, it’s a chance to bring together everything from the spiritual, which is part of Taekwondo, to the very public. It’s a kind of museum and arena where Taekwondo can be made vivid to someone who doesn’t know anything about it. It actually calls into questions this whole public/private, natural/artificial question. We’re really excited about it because it’s going to force us to think about this.

AIArchitect: You’ve spoken about how you don’t believe in natural landscapes—that there is some level of artificiality in any developed landscape. How does this express itself in your work? AIArchitect: You’ve spoken about how you don’t believe in natural landscapes—that there is some level of artificiality in any developed landscape. How does this express itself in your work?

Marion Weiss: Looking at Seattle, we had to do some very artificial things to introduce wildlife; for instance, with the salmon habitat at the water’s edge, to re-establish nature. But we had to do something entirely artificial above to create a continuous landscape over a highway and train tracks.

AIArchitect: You’ve established a record of being constructively challenged by site conditions that might disturb or dissuade other architects—whether they might be deemed too extreme and beyond remediation, as in Seattle, or unsophisticated and banal, like the surrounding suburban housing at your Olympia Fields Park and Community Center project in Illinois. Can you always squeeze quality designs out of every site? Have you ever found a site you couldn’t love?

Michael Manfredi: Not yet.

Marion Weiss: We have this predisposition to be especially excited about what others might perceive as orphan sites. It’s the extremities of distinctions between what a place appears to be and what it might be that excites us. If anything we’re energized by things that seem impossible.

AIArchitect: Your approach to integrating landscape architecture with architecture seems explicitly to disavow the Modernist “object in space” model of independent, sculptural form. Is this something you’ve self-consciously pursued? AIArchitect: Your approach to integrating landscape architecture with architecture seems explicitly to disavow the Modernist “object in space” model of independent, sculptural form. Is this something you’ve self-consciously pursued?

Michael Manfredi: I think it is conscious; very much so. We’ve grown disaffected with the idea that the architect produces purely a sculptural object that exists as an isolated element. Our generation is very interested in the idea of engagement. The idea that you make a building as an object, as a sculpture, is an idea that’s no longer relevant in our much more dynamic and complex society.

Marion Weiss: It can still have a strong formal or sculptural presence, but it has to have a capacity to engage, control, and be energized by those things around it, and maybe even energize those things around it. A building as a pure object is at great risk when the circumstances around it change, and a project that is already engaged with those circumstances has a greater chance to thrive even as things change.

AIArchitect: So you do you feel that this approach handicaps your ability to create iconic architecture?

Michael Manfredi: No, far from it. Out of the idea of constraint can come true originality.

Marion Weiss: It’s also the lens of what an icon is. We’re used to reading first and foremost the profile against the sky as the thing that marks an icon, whether it’s a tower or a sculpture, a man on a horse, or the towers in Dubai, but an icon is that which is memorable, and, arguably, that is going to be something that’s going to change depending on the audience.

AIArchitect: Who are some of your favorite contemporary architects?

Marion Weiss: Alvaro Siza has been an interesting character for us because of his search to create space, architecture, and simplicity in contemporary ways. It is something that has always evolved, but evolved with site. That’s one extreme of the situation. Frank Gehry has made the world a much fuller place for us to work as architects because he has broken the curse that has been cast over many institutions to think that if anything is different and not contextual, it’s going to be a crisis. The credibility and the beauty of the Guggenheim Bilbao has raised the courage of a bigger audience than any other architect.

AIArchitect: Do you consider Gehry a formalist and, if so, is that a bad thing? AIArchitect: Do you consider Gehry a formalist and, if so, is that a bad thing?

Marion Weiss: I think he’s a profound formalist and it’s a fantastic thing.

Michael Manfredi: Formalism can be misconstrued as pejorative, but, in the end, we designers work with forms.

AIArchitect: So then it is disingenuous for architects to point to another architect and decry them as a formalist?

Michael Manfredi: Yes.

Marion Weiss: We are formgivers. If we do nothing but give forms, we are at least beginning to touch on the core obligation of our profession. |

Summary:

Summary: Marion Weiss, AIA, and Michael Manfredi, FAIA, came to the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., on September 15 as part of its Spotlight and Design lecture series to discuss their still-young firm’s projects, epically their Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle. They also sat down with AIArchitect Associate Editor Zach Mortice.

Marion Weiss, AIA, and Michael Manfredi, FAIA, came to the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., on September 15 as part of its Spotlight and Design lecture series to discuss their still-young firm’s projects, epically their Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle. They also sat down with AIArchitect Associate Editor Zach Mortice. AIArchitect:

AIArchitect: AIArchitect:

AIArchitect:  AIArchitect:

AIArchitect:  AIArchitect:

AIArchitect: