| Urban Re:Vision Competition Brings Urban Farming and Net-Zero Energy to Texas Community sustainability nonprofit places Dallas at the top of its urban triage list How do you . . . design a residential mixed-use urban farming building that helps to rehabilitate a sprawling and disconnected Middle American city? Summary: John Dillinger said he robbed banks because that’s where the money was. Urban Re:Vision has chosen a sprawling, freeway-choked Middle American city for their first full design competition because that’s where the most typical urban design problems are.

Little Architecture’s Entangled Bank, against the Dallas skyline. Image courtesy of Little Architecture. Urban Re:Vision, a San Francisco-based nonprofit that sponsors design competitions meant to improve the sustainability and livability of cities, searched all over the nation for an ideal site to build on, and found one in Dallas—known more as a capital of 20th century fossil fuels than as a standard bearer for contemporary sustainability. They enlisted the help of Mayor Tom Leppert, city agencies, various community stakeholders, and an actual client in a quest to liberate radical sustainability from the coastal elite cultural sphere that it’s usually associated with in order to address a wide swath of problems average American cities face. Dallas, like many places, is wide and sprawling, the least dense of any American city its size. Its central business district is disconnected from the rest of the city and is wrapped in neighborhood-dividing underground freeways. There’s an acute lack of public transportation, and socio-economic segregation flows from all of these urban rifts. “We wanted a midsize city in the middle of the country with issues that everyone could relate to,” say Eric Corey Freed, an Urban Re:Vision board member and founder of organicARCHITECT in San Francisco. “If we did this in Portland you would read, ‘Oh, there goes Portland again with a great, cool thing we don’t have in the rest of the country.’ I don’t think that would have been as effective.” Urban Re:Vision, has hosted several purely theoretical competitions in the past. Now, they’ve found an actual site just outside of downtown Dallas and an actual nonprofit client (Central Dallas Community Development Corporation) willing to build there. Announced in May, three winners (Little Architecture, a team composed of David Baker and Partners Architects and Fletcher Studio, and a Portuguese team of Atelier Data and Moov) will all meet with their client in late August or early September to negotiate building their mixed-use residential designs.

Little Architecture’s design features winding path of elevated walkways that take visitors and residents through educational spaces, to urban agriculture terraces. Image courtesy of Little Architecture. All competition entries had to operate at net-zero energy, waste, and water consumption and focus on urban agriculture as a way to re-knit disassociated pieces of urban fabric. Urban Re:Vision’s competition goals are ambitious, but they don’t focus on building shining, new eco-cities from nothing. They are exclusively interested in retrofitting existing cities, because these kinds of design solutions offer replicable lessons for other communities that single-swath master plans that rise out of deserts cannot. The competition focuses on sustainability as an energy and resource-use ideal, but also as a social ideal with the acknowledgement that no person or community is sustainable in isolation of any kind—economic, social, environmental, etc. The competition received 121 entries from all over the world, which were judged by a jury of sustainability experts including Freed and Cameron Sinclair, Assoc. AIA, of Architecture for Humanity. The design site is next to Dallas City Hall in a run-down and dilapidated commercial and residential neighborhood. Its total budget is $60 million, but funding is still being rounded up. The Central Dallas Community Development Corporation (CDCDC) has two blocks that are available for development, but the competition only requires designers to use one. It’s hoped that building there will spark a wave of sustainable development in the area. “We think it can be a catalyst for a part of the city that has been underdeveloped,” says John Greenan, executive director of the CDCDC. The path to sustainability The design by Charlotte-based Little Architecture consists of a 30-story tower with a vertical farming green screen across the east façade. It sits on a seven-story podium with a winding path that takes residents and visitors through sustainability education spaces and urban farming plots, up to a rooftop terrace. The podium also contains live-work spaces. This “meandering path,” as its designers call it, takes people through an organic slow food restaurant, an organic culinary institute, environmental learning lab, and an urban farming institute. Via elevated walkways and bridges, visitors find themselves in vast urban farming plots that will include grain fields. “When [people] get to the end of the path, they have more skills and abilities that they can contribute to society,” says Brad Bartholomew, AIA, of Little Architecture. “They’re geared to the revitalization of the human spirit. I think about that as a resource.” Little Architecture calls the project The Entangled Bank after Charles Darwin’s observations about the intense interconnectedness of all ecosystems.

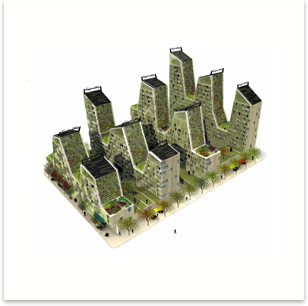

Atelier Data and Moov’s design. Image courtesy of Atelier Data and Moov. The building’s green screen will have 80,000 square feet of vertical farm land in the form of stackable planter boxes that plug into the screen. This screen will be accessible from large “sky pastures” (the designers are hoping to integrate livestock into them) placed every four levels in the tower. From there, residents will climb ladders to get to their vertical planter boxes. Each of the building’s 500 residential units will have enough photovoltaic panels to generate all its own power, mostly on the southeast and southwest façade. A copper tubing system on this side will heat water for residents as well. The interplay of glass and PV panels creates a rich graphic image (aided by subtle cantilevers and recessed sections) in the 773,000-square-foot building, and Bartholomew says this was largely determined by program and privacy levels. Bedrooms facing the southeast and southwest will have opaque PV panel walls; living rooms will use glass. Little Architecture’s design is perhaps the most practical of the winners—but Bartholomew prefers the word “developable.” “I think that’s sustainable—not to out-design your means in terms of how you can develop your project,” he says. Crossover appeal The San Francisco-based team of David Baker and Partners Architects and landscape design firm Fletcher Studio decided to look beyond the competition’s immediate site and develop broad, axial urban greenways that stretch out into Dallas and cross over at the building site, forming an X, hence the name of their project—XERO. From a 16-story tower on each of the two site blocks, one axial greenway would follow the contours of the nearby Trinity River, as a park and linear orchard. The other would sprout up from what is now a linear progression of mostly abandoned lots and underutilized properties like parking lots.

XERO’s south façade is covered in photovoltaic panels and trellised green walls. Image courtesy of David Baker + Partners / Fletcher Studio. This method of reaching urban agriculture and public green space beyond the confines of the CDCDC site was immediately apparent to both of the project’s primary designers, Ian Dunn, AIA, of David Baker and Partners, and David Fletcher, of Fletcher Studio. “This whole idea of the crossing greenways came within 20 minutes of our first meeting,” says Fletcher. The two bands of landscaped green that define the project are an attempt to better integrate the dense downtown with the sprawling surrounding neighborhoods separated by a buried freeway, and to create pedestrian interest and destinations in an automobile-focused city. Dunn calls this an “archetypal problem” in American cities, and his design is meant to break up the waves of freeway belts and commuter byways to create a more walkable, livable, fine-grained urban experience. And to truly do that, he had to look far beyond the single block the competition had given him. “It’s something that’s applicable to a lot of these cities that have dense central business districts surrounded by freeways and empty lots,” he says. “You’re not going to fix the problem with a central tower. The problems are much more endemic.” The team’s two 340,000-square-foot buildings are long and narrow—only 30 to 40 feet wide to aid cross ventilation and solar penetration. The south façade is covered in green screens of trellises and hydroponic trays, as well as PV panels. The north façade features slightly cantilevering, square porthole-like window sections that look out to downtown Dallas. Metal panels will cover sections of the building not encased in glass, green screens, or photovoltaics. Each building will also have two sky garden incisions that will be landscaped and planted. These buildings will lie on top of a podium that cantilevers outward over urban agriculture fields and also holds plots of crops on its roof. The entire complex will be surrounded by a large plaza filled with urban agriculture plots. Townhouse residential units and versatile retail and commercial spaces (from a single work stall to a complete storefront) will fill out the rest of the building podiums, inviting craftsmen, artists, and urban farmers in to sell their wares.

Photovoltaic panel-skinned telescopic volumes that are dotted with green screens reach around the edges of the building, peaking towards the north façade, like an amoeba enveloping another organism. Image courtesy of David Baker + Partners / Fletcher Studio. It’s a more spontaneous and informal vision of building community through sustainability than what Little Architecture imagined. Bartholomew’s plan, with its specifically programmed education spaces, approaches sustainability as an avocation to be perfected through serious and specifically directed study. XERO’s approach is more laissez-faire, and more willing to let people organize themselves. It considers social sustainability a natural byproduct of combining diverse people with diverse skills in a dynamic and fertile urban environment. The XERO design features geothermal heat pumps for heating and cooling and gray water recycling systems that will retain and clean runoff water before it makes its way to the Trinity River. Appropriately then, Dunn and Fletcher call the design a “performative landscape”—a landscape that actively shepherds and restores natural resources by generating energy from the sun, cleaning polluted water, generating food, and creating microclimates. Formally, the XERO buildings use organically irregular bulges, curves, and incisions to break up otherwise rectilinear massing, especially on the PV and greenscape-dominated south façade. Photovoltaic panel-skinned telescopic volumes that are dotted with green screens reach around the edges of the building, peaking towards the north façade, like an amoeba enveloping another organism. It’s a strident visual metaphor for a project in a city that has largely resisted the progressive creep of sustainable development. XERO will have succeeded if this synthetic organism is able to reproduce and spread beyond the greenway arteries that will extend from it, across the entire city. Fletcher likens the form of his design to a chipped arrowhead, but he’s cautious about embracing any vaguely vernacular Old West motifs that are going to seem forced, unnecessary, or too easy the morning after. And it’s hard for both Dunn and Fletcher to isolate a singular idea of Dallas’s overriding architectural character, which was an important focus of the Urban Re:Vision competition. This project already rethinks the entire consumer relationship to urban food and energy, and Fletcher (a Texas native) wonders if it might be a good opportunity to let it rethink local formal traditions as well, and start over. “It’s a better habitat for a new Dallas vernacular than any other building I can think of there,” he says. Hungry for green |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Global Design Contest Seeks Architects’ Insights, Visions

› Open Architecture Challenge Gives Students and Teachers a Say in Classroom Design

› Goody Clancy’s New Orleans Masterplan Tries to Balance Economic Growth with the Need to Mend the City’s Urban Fabric

› From Farm to Market, Down the Stairs, Around the Block

› Shaker Heritage Inspires Masterplan for Historic Village

› BTA’s Big Plan in Baltimore Has Room for All the Little Places

› A Year Later, Greensburg Will Rebuild with Platinum

› New Songdo City Looks Back at the New World for Older Urban Models

› Green Roofs on Chicago’s Red Line

Visit the AIA’s government advocacy Rebuild and Renew site.

See what the Center for Communities by Design is up to.

See what the Committee on the Environment Knowledge Community is up to.

Do you know the Architect’s Knowledge Resource?

The AIA’s resource knowledge base can connect you to the AIA Best Practices report on green roof design.

See what else the Architects Knowledge Resource has to offer for your practice.