| |

BTA’s Big Plan in Baltimore Has Room for All the Little Places

Even with a dramatically altered urban landscape, the Charles North master plan leaves cracks, fissures, and incubators for community to grow

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: BTA’s master plan for the Charles North neighborhood of Baltimore balances sweeping urban renewal with smaller-scaled programmatic flexibility to preserve and let rematerialize the city’s creative human capital. This plan is consistent with the firm’s social realist design philosophy, which privileges the social links encouraged by the built environment over formal flourishes. Summary: BTA’s master plan for the Charles North neighborhood of Baltimore balances sweeping urban renewal with smaller-scaled programmatic flexibility to preserve and let rematerialize the city’s creative human capital. This plan is consistent with the firm’s social realist design philosophy, which privileges the social links encouraged by the built environment over formal flourishes.

How do you . . . create an ambitious and focused urban renewal master plan that leaves room for small-scale, ad-hoc programs and uses while still respecting the neighborhood’s history and building typology?

Do You Know the Architect’s Knowledge Resource?

The AIA’s resource knowledge base can connect you to the podcast presentation “Sustainable Design in the Post-Katrina Era,” a briefing on how cities should redevelop sustainable communities in disaster-prone areas, delivered at the 2007 AIA Convention.

See what else the Architect’s Knowledge Resource has to offer for your practice.

All images courtesy of the architect.

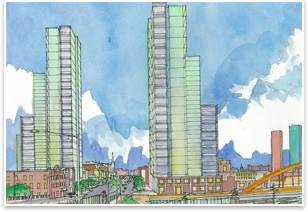

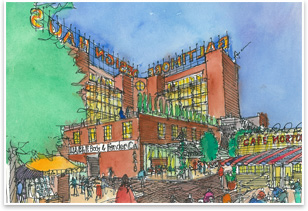

1. A mixed-use live-work tower, typical of the plan’s high-rise developments.

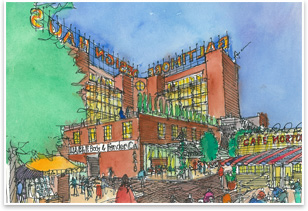

2. Penn Station and its pedestrian concourse.

3. The Design Center district of Charles North.

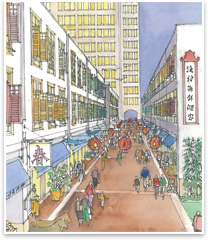

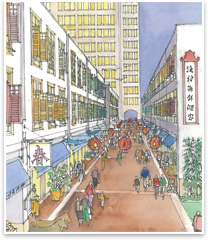

4. The Asia Town district of Charles North.

One of Modernism’s chief urban planning failures was an ignorance of small-scale urban fabric. As architecture is now privileged to know, nooks, crannies, alleyways, and other kinds of found and improvised space often are what holds the human capital, history, and thus the identity of communities. New gleaming towers, expansive plazas, and manicured landscapes that don’t acknowledge this are bound to be perceived as alien and culturally disruptive, no matter how much better they may appear to function. The lesson may seem to be “make no large plans” (or outsized projects—Cabrini Green, Pruitt-Igoe, etc.).

But the work of one firm, Benjamin Thompson Associates of Cambridge, Mass., has charted a path between ambitious neighborhood-scale redevelopment and disempowered design timidity. The strongest elements of the BTA Architects master plan for the Charles North neighborhood in Baltimore are how it finds new ways for small-scale, granular pieces of urban fabric to grow that is consistent with the area’s building stock and urban typology, thus making the project socially sustainable. And ecologically sustainable. BTA intends for the neighborhood to be entirely carbon neutral.

Where two elements meet

BTA has been doing this kind of urban renewal planning and design work since their 1976 Faneuil Hall Marketplace project in Boston, which recently won the 2009 AIA Twenty-five Year Award. Their Charles North plan in Baltimore focuses on roughly 15 blocks in the north-central part of the city that lie 16 blocks north of Inner Harbor, the city’s best known urban renewal project, which BTA worked on as well. Charles North is anchored by the intersection of North Ave. and Charles St., both major thoroughfares, and Baltimore’s Penn Station to the south. Otherwise, this historically commercial and industrial neighborhood has suffered from sadly typical deindustrialization, disinvestment, and automobile-aided flight to the suburbs for decades. There has been no new construction in Charles North since 1980.

But today, Baltimore is experiencing a nascent civic renewal while still battling a downward spiral of flagging industrial economies. It’s exactly this contrast that has put Baltimore closer than ever to the cultural zeitgeist and popular imagination of the day. This contradiction has also made the city a particularly apt fit for BTA’s design and planning philosophy. In all of their work, their firm emphasizes oppositional elements they call “ecotones.” These are places where two or more systems of activity come together, forming highly desirable natural or built environments. (For instance: at the beach, land and sea meet, and desirable urban environments are often the border between two distinct neighborhoods.) The Charles North plan reflects this idea with the subdivision of individual districts within the neighborhood, each anchored by different entertainment and intuitional entities. Formally, BTA’s work reinforces the ecotone principles by creating porous, open boundaries between public and private spaces.

Parts of the whole

BTA’s plan puts its first new elements in place in one to two years, but BTA architects see Charles North’s transition as taking place on a 30-year timeline.

Some of the individual districts:

- Penn Station is Maryland’s most important rail hub and the largest potential generator of foot traffic in the neighborhood. Its renovation will be modeled on BTA’s renovation of Washington, D.C.’s Union Station in 1988. A concourse of shopping and other commercial amenities will extend to the north, leading visitors into the neighborhood past a conference center, boutique hotel, and a landscaped public lawn. This part of the plan is expected to take four to seven years. There will also be park space at the south end of this site that extends up as a border to the northwest.

- The Backstage District borders Penn Station to the north. BTA’s plan anchors it with the extant Charles Theater cinema. This area is envisioned (like much of the plan) as a Jane Jacobs-inspired, mixed-use neighborhood of high-density residential towers with different programs at lower levels, especially small-scale business incubator spaces. These spaces will offer entrepreneurs, designers, and artists rental space at reduced rates and are one way the Charles North plan creates spaces for the character and identity of the neighborhood to fluidly seep back into its altered urban fabric.

The Design Center to the west is to become an institutional neighborhood dominated by higher education design programs (like the Maryland Institute College of Art) and other design-oriented groups, like the AIA. It will contain a mixed-use dormitory and apartment tower for students. The Design Center to the west is to become an institutional neighborhood dominated by higher education design programs (like the Maryland Institute College of Art) and other design-oriented groups, like the AIA. It will contain a mixed-use dormitory and apartment tower for students.- The northernmost section of Charles North is slated to grow into Asia Town, a Pan-Asian community of Korean, Japanese, Chinese, and Middle-Eastern residents and entrepreneurs. Though there is already an Asian presence in the neighborhood, it will require the dominant landowner in the area to attract such people to the neighborhood in much greater numbers for such a distinct cultural district to emerge. This could be a difficult task, as a traditional “Chinatown” has never taken root in Baltimore. Similar to the Backstage District, this area will contain a mix of uses and hundreds of thousands of flexible retail, gallery, studio, and office spaces, as well as incubator spaces. The master plan also calls for row houses to be reconceived as Asian-style shop houses, where business owners split work and living space in one building.

The Back Story

The AIA is taking a leading role in planning of the Charles North Design Center and finding a role for the Institute within it. In June, Klaus Philipsen, AIA, of AIA Baltimore’s Urban Design Committee, participated in a design charrette for the Design Center at a local gallery, bringing in artists, architects, government officials, community members, and NGO officials. They’ll have a final plan in place by this spring. “Right now, we’re trying to get as many pieces into the tent as possible, and at the end of the six months we’ll know better [what] we’ll focus [on],” Philipsen says.

No matter what form the Design Center takes, Philipsen and others want to make sure there is a strong multidisciplinary emphasis, with contributions from several schools and designers across many different media.

“We haven’t had a place for discussions about that until now,” says AIA Baltimore President Lee Driskill, AIA.

“Our approach to bring three institutions of higher education that have different backgrounds and combine architecture with art and design—and aim for interdisciplinary work, research, and community service—seems to be rather novel,” Philipsen says. “There hasn’t been an exact precedent.”

Letting Baltimore be Baltimore Letting Baltimore be Baltimore

Another way BTA’s plan allows the neighborhood’s granular details to persevere and reemerge is its use of alley spaces. The Charles North plan envisions them as pocket parks, sculpture gardens, galleries, and street markets—any use that will build on the area’s creative human capital and encourage pedestrians to permeate the neighborhood. “Instead of thinking of alleyways as service spaces or the back-of-house, think of them as active frontage,” says Philip Loheed, AIA, a principal at BTA.

This is perhaps the most innovative feature in a master plan that doesn’t wield an overbearing design hand. It’s mostly concerned with letting Baltimore be Baltimore.

“We want to preserve as much of the existing fabric and history of the place as possible, and yet inject substantial new density, investment, and other activities into the neighborhood,” says Loheed. “Not only are the character and the spirit of the place embedded in the people, but also in the buildings.”

And, Loheed hopes, the people are embedded in the plan. The firm has been meeting with 30 different stakeholder groups (entrepreneurs, community groups, developers, etc.) since last winter. Loheed says this kind of community buy-in from diverse groups is the only way such a project can build a sustainable multi-ethnic, socioeconomically diverse neighborhood.

Social realism Social realism

BTA’s design philosophy clearly values the programmatic needs and expectations of a community over design exploration and virtuosity. Loheed calls this approach “lifestyle architecture” and has a quote by firm founder and AIA Gold Medalist Benjamin Thompson ready: “Architecture is not pure structure or a sculpture, but a setting for an enriched way of life.”

It’s a social realist view of architecture—a strict reminder that form is only a means to an end, and that the relationships facilitated by form (even if they’re considered unsophisticated or unresolved) are supreme.

The economic and social implications of rebuilding this Mid-Atlantic neighborhood after decades of disinvestment have made Loheed think of another community leader and urban organizer whose ear he would like to have: President Barack Obama. Though it’s early in the process and no buildings have been designed yet, Loheed says he sees the Charles North plan as a model to be followed across the nation, and he’s sending the president a copy of it. “I’m reading your book, you can read mine,” will be his pitch. If the great urban planning admission of today involves architects admitting what they don’t know (namely how to dictate wholesale building-by-building neighborhood plans), then perhaps the tradeoff is optimism that the government has now learned to facilitate competent urban policy. |

|

Summary:

Summary: Planning and Urban Design Standards

Planning and Urban Design Standards The

The  Letting Baltimore be Baltimore

Letting Baltimore be Baltimore Social realism

Social realism