New Songdo City Looks Back at the New World for Older Urban Models New Songdo City Looks Back at the New World for Older Urban Models

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

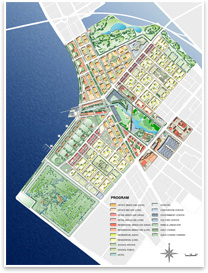

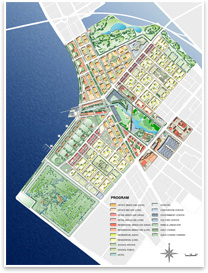

Summary: The master plan for South Korea’s New Songdo City is built on Western urban models, hybridized for the developing Asian world. The entire edge city development is oriented along a long, diagonal commercial downtown office core.

How do you … design a master plan for a developing world city that draws on established models of urbanism?

As architects across the globe are tasked with creating new, fully formed edge cities from Abu Dhabi to China, a fundamental and uniquely 21st century design dilemma calls out for an answer: How does one design an authentically urban place that has no historical urban context?

None of these projects has been completed yet, so no one can say they’ve conclusively solved such a problem, but a variety of approaches has emerged, from drawing upon the fractious, ad hoc urbanisms created by the disruptions of globalism to relying on established city models. Kohn Pederson Fox’s (KPF) master planning effort for New Songdo City just beyond Incheon, South Korea, relies on an incrementalist method of adapting established, often Western urban models and applying them to Korea. Lead designer James von Klemperer, FAIA, calls this model “reference and hybrid.” None of these projects has been completed yet, so no one can say they’ve conclusively solved such a problem, but a variety of approaches has emerged, from drawing upon the fractious, ad hoc urbanisms created by the disruptions of globalism to relying on established city models. Kohn Pederson Fox’s (KPF) master planning effort for New Songdo City just beyond Incheon, South Korea, relies on an incrementalist method of adapting established, often Western urban models and applying them to Korea. Lead designer James von Klemperer, FAIA, calls this model “reference and hybrid.”

Itself as edge city to an edge city (Incheon is connected via subway to Seoul, Korea’s capital and largest city, 30 miles to the east) New Songdo City sits on an infill island on the Yellow Sea. Across a 7.5-mile-long bridge towards China is the Incheon airport. Trade with China has led this part of South Korea to experience the kind of growth that powers a massive master plan like New Songdo City. The new city will be an international zone of commerce, free of many of the restrictions and taxes of the Korean government, according to the New York Times. New York-based KPF worked side by side with the project’s developer, Gale International, in an integrated design team.

The new city will cost $35 billion and will be about 100 million square feet of built space. Nearly half of this will be for commercial office space. KPF is designing 10-20 buildings for the city as well, and some will open next year. This is the first time foreign companies have been allowed to own South Korean land. Von Klemperer says this ultra-compact city will contain all the cultural and social amenities of a midsize metropolis, all within 1,500 acres, where 65,000 people will live and 300,000 people will work. The new city will cost $35 billion and will be about 100 million square feet of built space. Nearly half of this will be for commercial office space. KPF is designing 10-20 buildings for the city as well, and some will open next year. This is the first time foreign companies have been allowed to own South Korean land. Von Klemperer says this ultra-compact city will contain all the cultural and social amenities of a midsize metropolis, all within 1,500 acres, where 65,000 people will live and 300,000 people will work.

Symmetry and spine

KPF’s master plan details zoning, massing, setbacks, cityscape textures, and even color palette restrictions. Its central organizing feature is a strip of core commercial office space that runs from the northwest part of the development to the southeast. It bisects residential areas to the north and south, and is itself bisected by a large park space. This strip is also at the crossroads of retail and cultural amenities. Von Klemperer says this central organizing locus follows anatomical forms, working as a “spine” that gives the city “bilateral symmetry” in structure and support.

“It allows different identities to attach themselves to two different sides as the city grows organically,” he says. “You never know if one will be the professional district, and the other will be the arts district, or whatever characteristics you get out of bilaterally symmetrical cities.” “It allows different identities to attach themselves to two different sides as the city grows organically,” he says. “You never know if one will be the professional district, and the other will be the arts district, or whatever characteristics you get out of bilaterally symmetrical cities.”

New Songdo uses another bilaterally symmetrical city (New York) as an urban master text in many ways. Its Central Park is modeled after the original, one group of buildings KPF is working on is referred to as New Songdo’s Rockefeller Center, and Von Klemperer compares another part of the development to Battery City Park. A water taxi service apes the canals of Venice, Sydney is represented by a waterfront cultural center reminiscent of Jorn Utzon’s, Sydney Opera House, and Hong Kong (the original Asian city of international commerce) is reflected in the city’s link to its airport.

Von Klemperer says the mega-block, car-dependent development seen in Seoul is not an appropriate model for New Songdo City, where smaller-scaled mixed uses are designed to make the city walkable and sustainable. The goal for New Songdo was to put together the best practices for every building type, and, thus, the development patterns of the world’s best cities (including New York) emerged as models.

“There is absolutely no geometric, scalar, material, or even use reference to grab onto locally there,” says Von Klemperer. “We had to reach far to find something that’s not immediately indigenous.” “There is absolutely no geometric, scalar, material, or even use reference to grab onto locally there,” says Von Klemperer. “We had to reach far to find something that’s not immediately indigenous.”

But once KPF found something, they didn’t drop it in New Songdo City unaltered. Many of the features of New Songdo are adapted to “Korean typology and Korean ecology,” with “references to landscape types of the Korean Peninsula,” says Von Klemperer. The most overt example of this is New Songdo’s 100-acre Central Park, which KPF designed as an openly democratic, egalitarian green space originally forged in 19th century America, and taken to a place where the most prized green spaces often come with intimidating names like the “Imperial Palace” and “The Forbidden City.” To adapt this model to Korea, KPF designed a park with literal references to local landscapes: mountains, hills, meadows, and beaches.

At building scale

The material and aesthetic palette of New Songdo leans heavily on glass in orthogonal, Modernist masses, but Von Klemperer says warmer, more humanistic textures and materials (like sandstone, terra cotta, and colored concrete) will be well represented, especially in residences. The current standard in urban Korean residential architecture are high-rises built in tower-in-the-park mode at uniform density levels, but New Songdo City offers more options. It modulates densities (highest in the central commercial strip and lower at the residential periphery) with other housing types, like row houses and town houses, which are another way KPF is adapting western urban typologies to Korea. The firm is also designing the 65-story Northeast Asia Trade Tower, which will be the tallest in the nation. Their Convensia Convention Center will be Korea’s largest column-free space and is designed as a series of volumes that look like overturned ship hulls.

Built-in sustainability Built-in sustainability

Many architects and developers creating such massive master-planned developments have seized on sustainability as a humanistic balance to match the ambition of city authorship, and New Songdo City has, too. It plans to be one of the greenest master-planned edge city developments in the world, which Gale and KPF will ensure with a design review board they will both sit on. “It will probably be the first city in the world where all the buildings will be LEED®-rated,” says Von Klemperer. The project recently won the first annual Sustainable Cities Award, sponsored by the Financial Times and the Urban Land Institute. Additionally, New Songdo has been selected as a pilot program for the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED for Neighbor Development rating criteria.

Despite Korea’s car-focused urban development patterns, New Songdo City is designed for Manhattan-style walkability. Beyond water taxis, there will be jitneys to the airport, bus services, and three stops on Seoul’s subway line. A complex gray water and black water processing system will harvest methane from black water and use it in power plants. A pneumatic trash collection system will improve waste processing efficiency, and the city’s Central Park will be landscaped so that maintenance is as low-impact on the land as possible—all of which will pay added sustainability benefits in land- and fossil-fuel-poor Korea. |

New Songdo City Looks Back at the New World for Older Urban Models

New Songdo City Looks Back at the New World for Older Urban Models None of these projects has been completed yet, so no one can say they’ve conclusively solved such a problem, but a variety of approaches has emerged, from drawing upon the fractious, ad hoc urbanisms created by the disruptions of globalism to relying on established city models. Kohn Pederson Fox’s (KPF) master planning effort for New Songdo City just beyond Incheon, South Korea, relies on an incrementalist method of adapting established, often Western urban models and applying them to Korea. Lead designer James von Klemperer, FAIA, calls this model “reference and hybrid.”

None of these projects has been completed yet, so no one can say they’ve conclusively solved such a problem, but a variety of approaches has emerged, from drawing upon the fractious, ad hoc urbanisms created by the disruptions of globalism to relying on established city models. Kohn Pederson Fox’s (KPF) master planning effort for New Songdo City just beyond Incheon, South Korea, relies on an incrementalist method of adapting established, often Western urban models and applying them to Korea. Lead designer James von Klemperer, FAIA, calls this model “reference and hybrid.”

“It allows different identities to attach themselves to two different sides as the city grows organically,” he says. “You never know if one will be the professional district, and the other will be the arts district, or whatever characteristics you get out of bilaterally symmetrical cities.”

“It allows different identities to attach themselves to two different sides as the city grows organically,” he says. “You never know if one will be the professional district, and the other will be the arts district, or whatever characteristics you get out of bilaterally symmetrical cities.”

Built-in sustainability

Built-in sustainability