A Year Later, Greensburg Will Rebuild with Platinum

The Kansas town nearly wiped off the map pitches in to see that it grows back green

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: After Greensburg, Kan., was almost wiped off the map by a tornado a year ago, the town has enlisted the help of Kansas City, Mo.-based firm BNIM to help them rebuild sustainably. The town has decreed that all city-owned public buildings larger than 4,000 square feet must be LEED® Platinum certified, and the architects and community nonprofits are working with residents to encourage and enable them to build their homes and businesses back using sustainable design practices. Community leaders say that Greensburg offers an opportunity to join together cultures that share similar values, yet occupy different cultural realms—sustainability expertise and rural Midwestern communities. Summary: After Greensburg, Kan., was almost wiped off the map by a tornado a year ago, the town has enlisted the help of Kansas City, Mo.-based firm BNIM to help them rebuild sustainably. The town has decreed that all city-owned public buildings larger than 4,000 square feet must be LEED® Platinum certified, and the architects and community nonprofits are working with residents to encourage and enable them to build their homes and businesses back using sustainable design practices. Community leaders say that Greensburg offers an opportunity to join together cultures that share similar values, yet occupy different cultural realms—sustainability expertise and rural Midwestern communities.

How do you … create and implement a sustainability master plan for a rural community that has had the vast majority of its building stock destroyed?

Just over a year after a tornado destroyed 90 percent of its built infrastructure, the small western Kansas town of Greensburg has adopted a two-phase master plan with a bold commitment to sustainability. All city-owned public buildings larger than 4,000 square feet must be LEED Platinum certified. Alone, this audacious initiative (they are the first town in the nation to make such a proclamation) won’t make Greensburg the sustainable model community on which it’s betting its future, so the town is enlisting the help of nonprofits, environmental consultants, and architects to help residents take the next step and apply sustainable design practices to their homes, businesses, and everyday lives.

Daniel Wallach’s community nonprofit, Greensburg Greentown, has been providing expertise to residents, raising money and donating supplies, and acting as a link between sustainability experts and the people of Greensburg. “The most important connection is with the residents themselves to make sure they understand and appreciate this initiative,” he says. “It has to be a grassroots effort in order to be truly sustainable.” Daniel Wallach’s community nonprofit, Greensburg Greentown, has been providing expertise to residents, raising money and donating supplies, and acting as a link between sustainability experts and the people of Greensburg. “The most important connection is with the residents themselves to make sure they understand and appreciate this initiative,” he says. “It has to be a grassroots effort in order to be truly sustainable.”

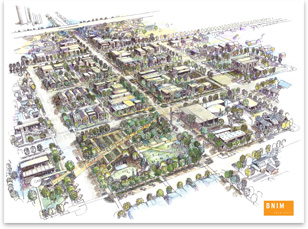

BNIM’s backyard

Kansas Governor Kathleen Sebelius invited Kansas City, Mo.-based BNIM to work as consultants after the May 2007 tornado, and the town approved the first phase of the their master plan in October. This plan detailed conceptual design schemes for downtown Greensburg, zoning refinements, and housing policy recommendations. That January, the Greensburg City Council approved the resolution that all public buildings be LEED Platinum certified. Additionally, BNIM is working on a plan that would power the city using all renewable resources and will include an eco-industrial park. In May, the town adopted the second phase of the sustainability-focused firm’s master plan that deals with parks and open spaces, cultural resources, economic strategy, and an implementation process for the entire sustainability plan. BNIM is responsible for designing several civic buildings in Greensburg: the city hall, a school, the downtown streetscapes, and the Big Well Museum—a tribute to the world’s largest hand-dug well, a museum type that’s seemingly ubiquitous yet somehow one-of-a-kind in the rural Midwest. A business incubator building and a John Deere dealership already have broken ground. Many of BNIM’s buildings will be under construction by this fall or winter.

All this activity has drawn keen interest from outside the town. Environmental consultant and U.S. Green Building Council co-founder John Picard has been working with Greensburg residents, and Leonardo DiCaprio is producing a television show on the new Planet Green network about the reconstruction efforts.

Same values, different spheres Same values, different spheres

Western Kansas is not typically thought of as a sustainability and progressive design hotbed, but BNIM’s designs are nonetheless humanistically contemporary and highly sustainable. Using mostly the same material palette the town used before the disaster (wood, brick, precast concrete) BNIM designed warmly Modernist buildings that announce their emphasis on contemporary sustainable design, but aren’t too strident about it. These designs are informed by many hours of community input and rebuilding goals that the town assembled, which emphasize wind energy, growth, and preserving the close-knit communal culture of the rural Midwest. All the goals walk a fine line between the potential cultural disruption of new built environment models and the preservation of Greensburg’s status quo way of life.

So far, 10 public buildings are committed to the LEED Platinum standard. Currently, there are only seven LEED certified buildings in all of Kansas.

Rachel Wedel, a project planner with BNIM, says residents will benefit from the fact that many social facets of small town life are also principles of sustainable design, like walkability, enlivened downtown cores and streetscapes, and pedestrian paths and trails. Wedel says that LEED’s urban infrastructure elements, like it’s emphasis on public transportation, make it unwieldy to apply to rural communities, even though standing in the center of a town like Greensburg (population 1,400) puts you “only a quarter mile away from every amenity in town.”

The citizens of Greensburg see the transition into a model of sustainable rural living as a way to inspire growth and stave off the population loss that is risking the future of many small agricultural communities across the nation, she says. “It’s almost a mob mentality, but it’s the most positive version of that you could find, because they’ve rallied around this idea that they will become a sustainable model community,” Wedel says. “Because they’re a smaller number of people, they hold each other accountable at a level that I think at an urban scale is more difficult to do.”

“The rate at which people have learned about LEED and about sustainable building is really kind of astonishing because this is a group that had on their plate a lot to do just to get their lives back in order, and to undertake this whole other level of education is really kind of heroic,” says Wallach. “They’re throwing around words like ‘LEED’ and ‘thermal mass.’”

Beyond western Kansas’s new vernacular explorations, Wallach says he’s most excited to see the cultures of sustainability and rural life join together in Greensburg. His goal is to help democratize the sustainability movement by taking its leadership and development out of the hands of coastal elites. “In rural cultures, elitism doesn’t exist,” he says. “They don’t say, ‘You’ve got to have studied something for a dozen years to be good at it.’ You’ve got to get buy-in from the people. If it were perceived as a top-down directive, it would not work.”

Challenges ahead Challenges ahead

Kim Alderfer, a Greensburg native, is the city’s assistant administrator, in charge of tracking funding for rebuilding projects and economic development programs. She talks about the challenges faced by the town, like finding contractors with sustainable building experience. Housing these workers is another problem. Lodging amenities are at least 30 miles away, and finding locally sourced sustainable materials for them to build with is tricky. Many residents of Greensburg were also massively underinsured after the tornado and their insurance settlements often only paid for a fraction of the cost of a new house. Most basically, the town has to deal with the urge to rebuild hastily while the sustainability gurus quibble and deliberate over zoning atlases and renderings.

Already, so much has been lost, but now Greensburg seems to understand that what’s left has to be a commitment to make patience pay off. “We’re not just making decisions for the next 5 years, we’re making decisions for the next 100 years,” says Alderfer. “We’ve lost all our history, so it’s pretty important to leave a legacy.” |

Summary:

Summary: