| Shaker Heritage Inspires Master Plan for Historic Village

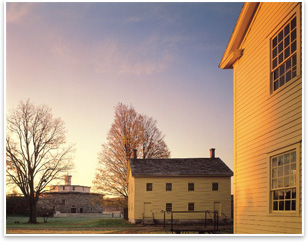

John G. Waite Associates, Architects’ comprehensive master plan for Hancock Shaker Village in Pittsfield, Mass, will give the village an opportunity to reflect on its heritage and assess the current condition and needs of its 20 buildings and 1,200-acre landscape. This collaboration between architect and client will create the future of this outdoor living-history museum and offer a guidepost for similar venues. The team is drawing from Shaker heritage and the Shaker commitment to living a principled life to address contemporary issues such as building community and sustainability. The project is slated for completion at the end of the year.

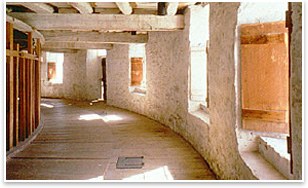

Evolving principles for the 21st century Spear says she looks forward to bringing the Shaker story to address contemporary issues like peace (the Shakers were pacifists) and building community and sustainability, noting the ways they sited buildings and reused materials, approached construction, and looked at things in a sustainable way. “I don’t think they necessarily knew or named it that, but that’s certainly the approach,” Spear says. “The same with organic gardening and the methods they used. They had tremendous technical innovation that we see within the building and building construction, including a water-power system in the early 1800s. All of those things can address issues that are important to us today.”

Lessons for other historic sites

These notions are also driving the master planning process. “One of the things we are looking at is the question of authenticity—what buildings are original, what buildings have been moved in there, what buildings have been heavily modified, because in the future the question of authenticity is going to be really important,” he concludes. ”We think it very significant that Hancock has survived as a real place.” |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Latrobe’s Baltimore Basilica to Celebrate 200th Birthday

› The AIA’s Historic Resources Committee

The Shakers called the Hancock settlement the City of Peace. Visit the Hancock Shaker Village online.

View the many other preeminent restoration, preservation, and adaptive reuse projects by John G. Waite and Associates, Architects.

Major funding for the project is being provided by a $100,000 State of Massachusetts grant through the Massachusetts Office of Travel and Tourism. The Getty Foundation is also providing $75,000 to support the project.

Waite adds that he believes authenticity is the key to increasing interest in historic sites and museum villages in general. “I think people are a lot more sophisticated today toward historic buildings than they were when Hancock Shaker Village was set up. One of the huge advantages that Hancock Shaker Village has is that it is an authentic village, a real place. There was a lot of thought given to its layout based on functional requirements as well as aesthetic requirements tied into their religion. It’s not something that should be compared to the other museum villages that are artificially created as museums.”

Waite adds that he believes authenticity is the key to increasing interest in historic sites and museum villages in general. “I think people are a lot more sophisticated today toward historic buildings than they were when Hancock Shaker Village was set up. One of the huge advantages that Hancock Shaker Village has is that it is an authentic village, a real place. There was a lot of thought given to its layout based on functional requirements as well as aesthetic requirements tied into their religion. It’s not something that should be compared to the other museum villages that are artificially created as museums.”