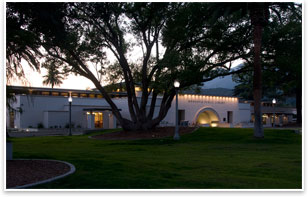

| Library on the Green Gonzalez Goodale’s New Monrovia Public Library opens its doors in a century-old park How do you . . . design a classically contextual library on a site that’s a highly prized civic park? Summary: To design the new Monrovia Public Library, Pasadena, Calif.-based Gonzalez Goodale Architects navigated their way through historicist concerns coming from local groups and a shared sense of reverence toward a century-old park. The result is a classically framed library open to new information needs and technologies but firmly rooted in local tradition.  The Monrovia Public Library at night. Photo courtesy of Derek Rath. Not long after the City of Monrovia, Calif., was founded in 1886, members of a women’s club started working up plans for a public library. The grassroots effort involved fundraising events to which guests were granted access through book donations instead of ticket purchases. The new Monrovia Public Library, which opened in May, was funded in a way consistent with the city’s history. After 10 years and three failed attempts to get funding from the state, the city funded its own $16 million library through a city bond and built it in less than two years. The new library is in many ways in line with that first library, but it’s not its direct successor. Between the first library, housed in a rented room, and today’s modern facility stand two other buildings.

The library is in Library Park, in the historic center of Monrovia. Photo courtesy of Magnus Stark. One, known as the Carnegie Library, was paid for in part by the steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, who agreed to donate $10,000 as long as the city provided the land for the building. It was then that the city purchased what is now Library Park, located in the middle of the city and still the site of the public library. The Carnegie Library, which opened in 1908, was outgrown by mid-century. In 1957 the city built a larger facility, and this is the building that the new Monrovia Public Library has just replaced. Darkness to daylight

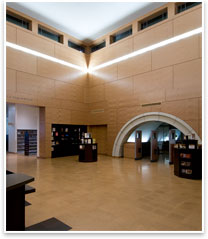

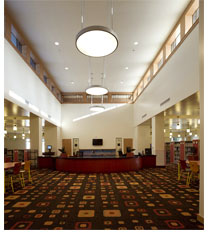

The library’s lobby. Photo courtesy of Magnus Stark. Beyond size, perhaps the most striking difference between the two buildings is their relationship to Library Park. Dick Singer, Public Information Officer with the City of Monrovia, says 90 percent of the old building had no windows opening out at all, mostly because every bit of space had been taken up by shelves to accommodate an overgrown collection. “The feeling of spaciousness [in the new building] is a stark contrast to the old building, which was dark and crowded,” he says. “This is a very open space, and the natural light makes a tremendous difference.” Part of the reason behind the openness of the new library is that David Goodale, AIA, design principal at Gonzalez Goodale, recognized the park as one of the library’s greatest assets.

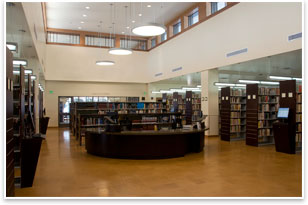

Natural light penetrates deeply into the interior of the library. Photo courtesy of Derek Rath. Goodale explains that in working with the site, the preservation of two huge, ancient trees became very much a part of the project. The trees now frame the building, a camphor to the south and a Morton Bay fig to the north. Library patrons can look out onto the under-canopy of those trees from the adult and children’s reading rooms in the front of the library, and onto the rest of the park from most of the other reading areas in the building. Goodale says one could walk through the building at any time of the day and have good visibility even with the lights off. Such continuity of daylight and views was achieved through a combination of perimeter windows and a central clerestoried hall that runs the full length of the library. Flexibility and collaboration Singer explains that library proposals came under severe scrutiny because the park is in the middle of Old Town Monrovia, the heart of the city, and for about a century there has been a library in that park. “People had proprietary interest in this project,” he says. “The challenge was to take everybody’s dreams and work them into a plan that accommodated everyone and served the needs of the city.”  Library stacks at the Monrovia Public Library. Photo courtesy of Magnus Stark. The architects met the challenge by shifting their focus from the style of the building to the relationships within and around it. The result is a classically framed library, rich in wood finishes, whose design is at once contemporary and rooted in Craftsman traditions. “We settled on a Craftsman feel because it defines the community,” says Singer. “It fits the town beautifully.” A new chapter in library design Goodale describes the building as a “flexible container” capable of accommodating a variety of audiences and programs over time. For example, Monrovia, a city of 40,000 residents, has 2,500 children in its summer reading club. The new library supports this enthusiasm for books through story nooks and a performance area for up to 125 children. Parts of this program might have a shelf life, but Goodale believes the space can change with the library’s program. The division of the program into areas devoted to different age groups is as much of a convention today as the dedication of space to new technologies. In addition to an audio-visual center, the new Monrovia library includes a public computer and technology area with about six times as many computers as the old library used to have. Cindy Dudenhoffer, director of information resources at Central Methodist University in Missouri, has been involved in a number of library renovations. Dudenhoffer explains that a major trend in library design in the past decade has been the move from a book-centered approach to the concept of “information or learning commons.” “Libraries are moving from ‘gatekeeping’ facilites to areas where information can be freely accessed,” she says. “Open spaces, collaborative areas, lots of tech centers, instructional technology-based classrooms are all making their way into library renovations.” In explaining the design’s approach to technology, Goodale says the building accommodates the idea of a library as a place of self-initiated discovery, but it remains deeply informed by a sense of reverence toward books. “We were inspired by a real commitment and continued belief in the integrity and beauty of books as an expression of culture,” he says. “Computers can go anywhere, so the idea of a library as a place for technology is something that I don’t see as particularizing. Books are what make it a special place.” Still, the new Monrovia library facilitates collaborative work and the use of technology as much as it provides opportunities for traditional research and contact with books. Singer praises its openness and says the city talks about the facility as a “community information center.” “This is a place where people can interact with information in any way that is possible,” he says. A greener park Goodale explains that LEED ratings do not involve a significant premium in terms of cost, so for his firm it’s a matter of course to pursue them. This project in particular was especially attractive because it had many LEED points built into it from the start. The new library would be built on a previously developed site, for instance and, being in the middle of a park, required no parking. (The library shares parking options, including street parking and several lots, with the surrounding business community.) Beyond the built-in LEED points, the architects created an environmentally sensitive design through sustainable cork flooring, a highly efficient HVAC system, carpets with high pre-consumer recycled content, recyclable furniture, paint and sealants with no or low Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), energy-efficient lighting, and a cool roof that reflects energy. The steel used in construction, too, contains a minimum of 25 percent recycled materials, and the library playground has a rubberized surface made largely of recycled materials. Finally, the planters surrounding the building were designed for water conservation. This last feature, along with the building’s low walls, helps erase boundaries between the library and the park. Goodale says he’s most delighted by way the building layers into the park with its exterior walls and landscape. Judging by the reaction of Monrovia residents, who are also delighted to have their park and library back, this seamless fit could be the project’s greatest accomplishment. |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› UC Berkeley School of Law Addition Sits Lightly and Gives Back What it Takes Away

› Library of Congress Gives Hillside Bunker a New Use

› Nine Libraries Called out for Design Excellence

› Nature Finds a Way: The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

› At Gonzales Goodale’s Wilshire Public Park, a Monument to a Dead Hero and Living Activism

› Delivering Big on a Small Budget

Do you know the Architect’s Knowledge Resource?

The AIA’s resource knowledge base can connect you to “Design for Social Sustainability at Seattle’s Central Library.”

See what else the Architects Knowledge Resource has to offer for your practice.

See what the Public Architects Knowledge Community is up to