Nature Finds a Way: The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

Toyo Ito’s first American project is a search for “generative order”

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: Toyo Ito’s design for the new Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive draws its form from nature-based systems. It balances rigid modularity with a capriciously unpredictable procession of spaces. By integrating such natural systems into contemporary designs so holistically, Ito’s work in this project and in others reminds viewers of the timeless intrinsic value of evolution as an agent of design. Summary: Toyo Ito’s design for the new Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive draws its form from nature-based systems. It balances rigid modularity with a capriciously unpredictable procession of spaces. By integrating such natural systems into contemporary designs so holistically, Ito’s work in this project and in others reminds viewers of the timeless intrinsic value of evolution as an agent of design.

How do you ... design a museum that emphasizes film and new media and derives its form from natural, evolutionary models?

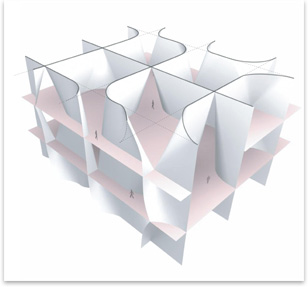

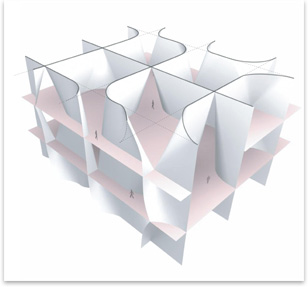

Evolution is the idea that time alone can sort chaos into order, while still breeding simplicity into complexity. By being an observant student of this kind of seemingly contradictory phenomena, Toyo Ito’s design for the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive at the University of California-Berkeley performs these same feats without the benefit of millennia upon millennia of incremental change. Ito’s first American building is conceived as a three-story stack of 16 hive-like chambers of thin concrete and steel walls that curve and taper, twisting like cloth in a breeze. It’s a design that expresses its formation as a product of rule-derived cellular expansion, as well as flowing, freehanded organic complexity. Evolution is the idea that time alone can sort chaos into order, while still breeding simplicity into complexity. By being an observant student of this kind of seemingly contradictory phenomena, Toyo Ito’s design for the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive at the University of California-Berkeley performs these same feats without the benefit of millennia upon millennia of incremental change. Ito’s first American building is conceived as a three-story stack of 16 hive-like chambers of thin concrete and steel walls that curve and taper, twisting like cloth in a breeze. It’s a design that expresses its formation as a product of rule-derived cellular expansion, as well as flowing, freehanded organic complexity.

“The space configuration is generated by a very simple rule, which repeats itself to reach a flexible space system,” says Ito, via e-mail from his office in Tokyo. “It is similar to a twig of a tree that follows a very basic rule when it grows. Searching for a generative order, sometimes looking into nature, has been our most important theme in design lately.”

Two museums Two museums

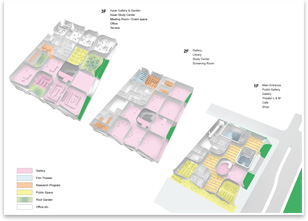

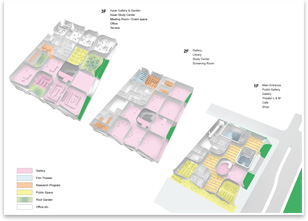

The museum selected Ito and his firm from a group of four competition finalists. The final design will be complete in 2009, and the museum is slated to be open by 2013. The Berkeley Art Museum maintains a well-regarded collection of mid-20th century art and one of the finest collections of historic Chinese paintings in the United States. The Pacific Film Archive (which shares the museum) has 14,000 films in stock, ranging from Japanese film, to Soviet silent films, to West Coast avant-garde cinema. Together they are one of the largest university museums in the nation in terms of attendance. Two theaters will show films. Free galleries will inhabit the bottom floor, and rooftop gardens will green the upper floors. The total cost for the 139,000-square-foot museum is estimated to be $146-165 million.

When Mario Ciamapi’s original 103,000-square-foot building, whose thick and severe concrete massing stands in sharp contrast to Ito’s amiably lighthearted building, was deemed not to be seismically sound, museum leaders began planning for a new facility. Located midway between Berkeley’s downtown and the university campus, the new museum is tasked with generating a collaborative town-and-gown synergy, aided by surrounding plazas and a largely transparent ground floor.

Evolutionary transition Evolutionary transition

For a building built to counter seismic instability, the Berkeley museum takes risks with its lightweight, flowing form. The walls are only five inches thick—three inches of concrete sandwiched between two one-inch-thick steel plates. There are no supporting columns. Ito says the structural system has been tested and used in Japan, where seismic concerns are just as important. These walls do more than define the edge of white box gallery space; they emerge as sculptural aesthetic works themselves. From gallery to gallery, the walls peel open, flop back, and curve around. Some converge at the floor, creating barriers between chambers. Some taper together from the bottom to the top, forming teepee-like openings, all offering seamless transitions that present gradual visual surprises.

“The walls of this building should be seen as [a] ribbon that flows through the space and [is] expressed as light,” Ito says. “In conventional white cubes, people move from one space to the other through an articulated threshold. Here, what we are trying to create is the experience where visitors, while passing through wider and narrower spaces, move from one scene to the next without actually noticing their boundaries. A visitor would walk along the continuous undulating wall and realize that he or she has arrived in a different space without really knowing it.”

The 16 chambers that make up the museum are vaguely curved squares, but subtle, seemingly evolutionary permutations make its layout resemble plant cells under a microscope—neither wholly uniform nor spatially ungoverned. Looking at renderings of the Berkeley museum’s procession of spaces is like observing a natural process that’s been pushed out of a staid and predictable pattern of cloning and into a Darwinian selection that splinters species from species. Ito calls it a “deformed grid” that could stretch on forever—a “section cutting” out of “continuous space,” like expanding and dividing plant cells. The 16 chambers that make up the museum are vaguely curved squares, but subtle, seemingly evolutionary permutations make its layout resemble plant cells under a microscope—neither wholly uniform nor spatially ungoverned. Looking at renderings of the Berkeley museum’s procession of spaces is like observing a natural process that’s been pushed out of a staid and predictable pattern of cloning and into a Darwinian selection that splinters species from species. Ito calls it a “deformed grid” that could stretch on forever—a “section cutting” out of “continuous space,” like expanding and dividing plant cells.

Ito’s design blends these open, fluid spaces with more isolated galleries and theaters for new media and film exhibitions. In terms of sustainability, the museum plans to be certified as LEED® Silver, though Ito and his clients are still developing the museum’s final systems.

Timeless nature Timeless nature

Lawrence Rinder, the director of the museum, says that very early on museum planners wanted their new building to have an organic quality—not an intuitive choice for a film and new media museum. He thinks this may have grown out of Berkeley’s natural topology, defined by its gradual transition from wilderness to urbanity.

Rinder’s museum had a unique and prized opportunity to give one of Japan’s most celebrated architects his first American commission, and Rinder says they’ve been toasting their choice as “inspired” ever since, especially considering how rigorously Ito’s concept grapples with the incorporation of organic systems.

This kind of integration of natural models and typologies has become a hallmark of Ito’s work. His Sendai Mediatheque in Sendai, Japan, which brought him to the world’s attention, supports itself with tree-like hollow tubes that are flexible enough to bend and sway with seismic disruptions and also contain rooms. One Berkeley professor described it as having a futuristic “Buck Rogers” quality of cinematic, sci-fi views—testament to the fact that the natural models Ito uses will have a timeless resonance in architecture into far-away futures. |

Summary:

Summary: Evolution is the idea that time alone can sort chaos into order, while still breeding simplicity into complexity. By being an observant student of this kind of seemingly contradictory phenomena, Toyo Ito’s design for the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive at the University of California-Berkeley performs these same feats without the benefit of millennia upon millennia of incremental change. Ito’s first American building is conceived as a three-story stack of 16 hive-like chambers of thin concrete and steel walls that curve and taper, twisting like cloth in a breeze. It’s a design that expresses its formation as a product of rule-derived cellular expansion, as well as flowing, freehanded organic complexity.

Evolution is the idea that time alone can sort chaos into order, while still breeding simplicity into complexity. By being an observant student of this kind of seemingly contradictory phenomena, Toyo Ito’s design for the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive at the University of California-Berkeley performs these same feats without the benefit of millennia upon millennia of incremental change. Ito’s first American building is conceived as a three-story stack of 16 hive-like chambers of thin concrete and steel walls that curve and taper, twisting like cloth in a breeze. It’s a design that expresses its formation as a product of rule-derived cellular expansion, as well as flowing, freehanded organic complexity. Two museums

Two museums Evolutionary transition

Evolutionary transition The 16 chambers that make up the museum are vaguely curved squares, but subtle, seemingly evolutionary permutations make its layout resemble plant cells under a microscope—neither wholly uniform nor spatially ungoverned. Looking at renderings of the Berkeley museum’s procession of spaces is like observing a natural process that’s been pushed out of a staid and predictable pattern of cloning and into a Darwinian selection that splinters species from species. Ito calls it a “deformed grid” that could stretch on forever—a “section cutting” out of “continuous space,” like expanding and dividing plant cells.

The 16 chambers that make up the museum are vaguely curved squares, but subtle, seemingly evolutionary permutations make its layout resemble plant cells under a microscope—neither wholly uniform nor spatially ungoverned. Looking at renderings of the Berkeley museum’s procession of spaces is like observing a natural process that’s been pushed out of a staid and predictable pattern of cloning and into a Darwinian selection that splinters species from species. Ito calls it a “deformed grid” that could stretch on forever—a “section cutting” out of “continuous space,” like expanding and dividing plant cells. Timeless nature

Timeless nature