BOOK REVIEW

Architecture and the Brain:

A New Knowledge Base from Neuroscience

by John P. Eberhard, FAIA

reviewed by Stephanie Stubbs, Assoc. AIA

Managing Editor

Summary: A year ago, John P. Eberhard, FAIA, gave us a special holiday present in the form of a story in AIArchitect. “Neuroscience and Architecture in A Christmas Carol: A tale of conception, perception, and proprioception”—replete with illustrations by the author himself—he used a cast of beloved characters to introduce the topic of how neuroscience studies can inform the practice of architecture. In the intervening year, Eberhard, the founding president of the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture and the second recipient of the AIA College of Fellows Latrobe Fellowship for Research, offered AIArchitect readers an article each month on the fundamentals of neuroscience and how they might relate to our profession. Now, he is bringing us another gift: Summary: A year ago, John P. Eberhard, FAIA, gave us a special holiday present in the form of a story in AIArchitect. “Neuroscience and Architecture in A Christmas Carol: A tale of conception, perception, and proprioception”—replete with illustrations by the author himself—he used a cast of beloved characters to introduce the topic of how neuroscience studies can inform the practice of architecture. In the intervening year, Eberhard, the founding president of the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture and the second recipient of the AIA College of Fellows Latrobe Fellowship for Research, offered AIArchitect readers an article each month on the fundamentals of neuroscience and how they might relate to our profession. Now, he is bringing us another gift:

Architecture and the Brain: A New Knowledge Base from Neuroscience, a book that forms a firm foundation for understanding this complex and fascinating field of study.

Why neuroscience? Why neuroscience?

If you are new to the subject of neuroscience, your first question might be, “Why study neuroscience for the sake of architecture?” In the preface of the book, Eberhard describes his reply to this often-asked question:

“I would ask the architect whether it would not be useful to know that there was some solid evidence based on fundamental studies to back up their intuitions. Once they understand that, the general answer is that it could be of great value to have such evidence when they try to convince clients to make good design decisions on behalf of eventual users.”

Architecture and the Brain offers an in-depth study of one of the most fascinating topics touching many facets of society today: neuroscience, defined broadly as study of the brain and the nervous system.

That architectural je ne sais quois That architectural je ne sais quois

Eberhard brings to this pioneering task both clear prose and strong sense of how to present information to architects. (He was, among his many incarnations, founder of the AIA Research Corporation and the School of Architecture and Environmental Design at SUNY Buffalo, and the head of the Department of Architecture of Carnegie Mellon University.) He has divided his presentation into seven subjects conceptually graspable by the architecturally inclined brain:

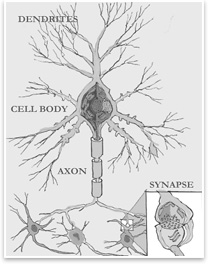

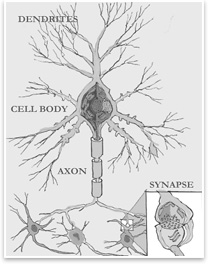

- Your Brain Experiences Architecture traces the history of the mind from prehistoric times in three phases that relate to the history of architecture from nomadic tents to the present. Interestingly, the modern creative mind, permanent architecture, and language all date back to a mere 10,000 years ago. This chapter also traces development of an individual human brain, from embryo through to specialized functions. This points to a critical finding immediately applicable to architecture: Babies born prematurely at six or seven months of age do not have fully developed seeing and hearing functions. Knowing that the development of these functions can be damaged by bright light or loud noise can inform the design of neonatal clinics. This critical chapter also explains the basic functions of the main parts of the brain, as well as how the brain transmits and receives basic signals.

- The Sensory Systems explains how our miraculous supply of gray matter transfers electrical impulses collected by our senses—visual, auditory, gustatory, olfactory, and tactile—and combines them with personal memory stores, thus allowing us to recognize a thing or an experience. It further describes our “sixth sense,” proprioception, which tells us where we are in space (which no one would deny is very important to architects).

- Emotions and Behavior in Architectural Settings explains our experience in architecture settings and how our brains may come preloaded with a “primary repertoire” of connecting neurons, to which we add a secondary repertoire of our experiences that creates our memory stores. This chapter also concentrates on the workings of the hippocampus (the memory center) and the amygdala (emotion center) and how they work together.

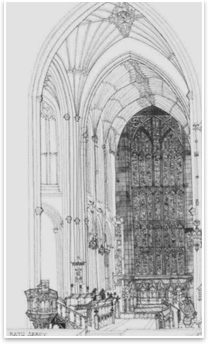

- Perceptions and Recognition of Our Environment tells how the brain takes sensory information about the environment and combines it with memory stores to map individualized perceptions, or “percepts,” and how the brain operates as a selective system, using and building on these “percepts.” These concepts tie to the architectural perceptions of proportion, harmony, and symmetry, some of which may be hardwired.

- Memory of Places and Spaces shows how our brains have special areas to store memories of faces and places. Although much research has been done on face recognition, little exists on its spatial counterpart. This chapter also explains how nothing is stored in direct long-term memory until it is experienced, which may help explain why lay clients show strong preference for traditional building types.

- Consciousness and Architecture explores different theories of what consciousness—called the “hard problem” of neuroscience—might be.

- Methods and Models for Future Research allows Eberhard to make the case for neuroscience study serving as a catalyst for architecture as a profession on the brink of a knowledge revolution. Introduction of an expanded knowledge base from neuroscience, he posits, likely will require introducing additional changes into architecture education. What is missing, with rare exception, from architecture education is research programs and clinical practice.

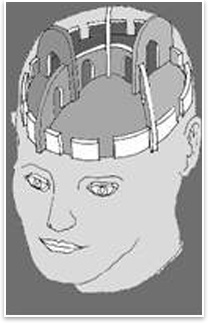

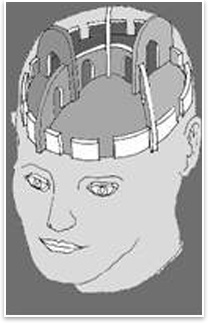

To sweeten the pot, Eberhard has drawn his own illustrations for the text and laid out the presentation in a way that will appeal to architects. To sweeten the pot, Eberhard has drawn his own illustrations for the text and laid out the presentation in a way that will appeal to architects.

A promise for the future

Is the neuroscience work presented here immediately applicable to architecture? Probably not, in its extant fledgling form. But neither was most of the visionary work in energy use in buildings—done 30 years ago, under Eberhard’s direction in the AIA Research Corporation—work that has matured into concepts of sustainability design we all embrace today.

This brings us full circle, to Eberhard’s introduction of:

“In the beginning, new ground must be carefully prepared; the old growth and underbrush removed, the soil tilled and raked; seeds planted, fertilizer spread, water provided in adequate amounts; while the sun provides ultraviolet and infrared rays creating a warm environment. When all of this has been done, through long hours of labor and required intervals of germination, a new young tree emerges.

Eventually, this young tree will bear fruit to reward those who have labored in the orchard. It would be foolish to chide those who are preparing the soil and planting the seed because there is yet no fruit. It would be unwise to water too much or allow the sun to parch the land. When the time has come, the fruit will be ripe and its substance will sustain those who harvest it. So it is with knowledge.” Eventually, this young tree will bear fruit to reward those who have labored in the orchard. It would be foolish to chide those who are preparing the soil and planting the seed because there is yet no fruit. It would be unwise to water too much or allow the sun to parch the land. When the time has come, the fruit will be ripe and its substance will sustain those who harvest it. So it is with knowledge.”

And if anyone should know, it’s John P. Eberhard, FAIA, long-time tiller of fertile architectural ground. |

Summary:

Summary: Why neuroscience?

Why neuroscience? That architectural

That architectural  To sweeten the pot, Eberhard has drawn his own illustrations for the text and laid out the presentation in a way that will appeal to architects.

To sweeten the pot, Eberhard has drawn his own illustrations for the text and laid out the presentation in a way that will appeal to architects. Eventually, this young tree will bear fruit to reward those who have labored in the orchard. It would be foolish to chide those who are preparing the soil and planting the seed because there is yet no fruit. It would be unwise to water too much or allow the sun to parch the land. When the time has come, the fruit will be ripe and its substance will sustain those who harvest it. So it is with knowledge.”

Eventually, this young tree will bear fruit to reward those who have labored in the orchard. It would be foolish to chide those who are preparing the soil and planting the seed because there is yet no fruit. It would be unwise to water too much or allow the sun to parch the land. When the time has come, the fruit will be ripe and its substance will sustain those who harvest it. So it is with knowledge.”