2/2006

The brain, the mind, and creation of memories

by John P. Eberhard,

FAIA

Founding president, Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture

I

grew up in the parsonage of Concordia Lutheran Church in Louisville,

where my father was the minister. In 1930, Ralph Adams Cram had designed

our Gothic-style church. My early memories of churches were shaped by

Concordia and visits to other Gothic churches with my father. When I

arrived at architecture school of the University of Illinois in 1948,

I was determined to be a Gothic church architect. A sea change from Beaux

Arts education to “Modern architecture” in 1949 gave me reason

to think otherwise. By the time I graduated in 1952, I was committed

to being a designer of “contemporary” churches.

I

grew up in the parsonage of Concordia Lutheran Church in Louisville,

where my father was the minister. In 1930, Ralph Adams Cram had designed

our Gothic-style church. My early memories of churches were shaped by

Concordia and visits to other Gothic churches with my father. When I

arrived at architecture school of the University of Illinois in 1948,

I was determined to be a Gothic church architect. A sea change from Beaux

Arts education to “Modern architecture” in 1949 gave me reason

to think otherwise. By the time I graduated in 1952, I was committed

to being a designer of “contemporary” churches.

When I began to practice, I found my clients all wanted either Gothic or Colonial churches. They had no previous experience—no memories—of so-called Modern church design. (My belief that I was right plus some good “salesmanship” convinced them to accept my designs, such as this 1955 church in Darmstadt, Ind.) In this article, we will explore how the brain and the mind work together to create such memories, and how memories affect people’s responses to architecture.

Your memory is now in overdrive

Your memory is now in overdrive

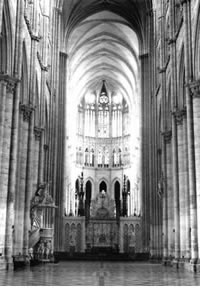

You may remember reading about the Cathedral

at Amiens in my January

AIArchitect article.

To remember, your mind searches various crevices of memory to find neurons

that can contribute to forming this recall. The thalamus sweeps your

entire cortex 700 times per second—like a radar sweep in the control

tower of an airport—looking for the neurons that are responding

to your effort to remember. The thalamus-sweep identifies each of the

millions of neurons so engaged because they are vibrating at 40 hertz.

The brain forms a “map” of these neurons in the frontal cortex

(where working memory resides) and your mind knows it has content for

a memory. This particular memory won’t stay in working memory any

longer than is needed to “complete your thought.”

When you are done with the process of remembering this article, or remembering Amiens, or remembering a similar cathedral you once visited, the mind sends all of the bits and pieces back into long-term memory. But, things your mind added or subtracted from the original memory-map will change this saved-again memory. That’s why you can never remember exactly the same thing twice. And that’s why eyewitness accounts of events about which people testify in court are never exactly what happened.

Your musical score is being created 700 times

each second

Your musical score is being created 700 times

each second

“You are the music, while the music is still playing” is a

well known statement in the neuroscience world. You can image that you

are a player in an orchestra in which each of the players is playing a

different instrument. Each produces a different sound and each plays a

different part of the melody. However, when you are using your mind, there

is no predetermined music that the components of your brain are playing.

The musical score is being invented as it is being played.

In this same way, your behavior is not the result of one simple response at a single moment in time, but rather is the result of a complex melody that began before that moment and that will be continued after that moment. And each part of your body is playing at the same time—but each part plays its own unique role. Some of these biological systems produce behavioral characteristics that are present continuously (e.g., you are breathing) and some of them only when the “music” of life calls for them to perform (e.g., your amygdala makes you afraid when you see a snake).

Thus, if you observe someone responding emotionally to the sounds of an organ playing when you enter the Cathedral at Amiens, you should recognize that she was having experiences before you saw her, and will continue to have more experiences after your observation. So, be careful in drawing conclusions about why there are tears in her eyes.

Your mind that remembers is a special process

While DNA shaped the brain you received from your parents and a long

line of ancestors, you did not inherit your mind. The marvelous process

that makes it possible to think about places you have been, contemplate

spaces you hope to visit in the future, and being aware of the present,

is created new each time you “turn it on.” You need a healthy

brain to provide your mind with memory processes, something that people

with Alzheimer’s can’t do.

There are two main types of memory:

- Declarative memory (or explicit memory) is the conscious recollection of facts and events, e.g., the capital of your state or who designed Fallingwater.

- Nondeclarative memory (or

implicit memory): encompasses skills that we learn (e.g., how to

ride a bicycle), reflexes (e.g., automatically removing your hand if

you touch a hot stove), or emotional responses (e.g., jumping back

in fear if you see a snake) that operate smoothly without conscious

recollection.

Four levels of consciousness

Remembering—forming memories and saving them—happens on more

than one level. Professor Antonio Damasio, the M.W. Van Allen Professor

and head of neurology at the University of Iowa, says that we have four

kinds of conscious interactions:

- Core consciousness comprises those response and recall processes that lie below the surface of your awareness. Your heart never skips a beat (we hope), you breathe in and out on a regular basis, your digestive system serves you well (we hope), and many other internal organs and processes operate without any conscious effort on your part. You are not even able to use your brain/mind to stop the action of your heart or stomach. Our body is organized around a number of automatic feedback loops. Our ability to regulate our metabolism, our reflex system, and the ability we have to condition our muscles through exercise. (As we will see in future articles, that does not mean that architectural settings have no impact on these internal organs. It is only that you are not conscious of these impacts and consequently have no memory of them.)

- Extended consciousness filters the thousands of sights, sounds, smells, and emotions produced every waking moment. Your brain can’t possibly register all of these sensory messages; it just shucks off the vast majority. The sights and sounds that make it through the filters of the mind are what we can respond to, store in memory, and think about later. Extended consciousness also provides you with an elaborate sense of self, an identity that is you. It places this self at a point in history. You are aware of your past life and your hopes for the future all the time you are keenly aware of your present environment.

- Autobiographical self uses all of your memories of the data of your life: your name, who your parents were, where and when you were born, what you like and don’t like, how you usually react to a problem, and so on.

- Dispositions. All of your memories, whether inherited from evolution and available at birth or acquired through experience, exist in dispositional form, waiting to become an explicit image or action. This is a key concept for architects. Dispositions are “packets of memories” or “files of an experience” that you store in many places in your brain once you have an experience. Let’s go back to the Cathedral at Amiens to see how this works. Once you have the experience, all of the sights, sounds, smells, textures, etc., are recorded, as well as your emotional response (i.e., a sense of awe), and any associated memories (e.g., “old French cathedrals are much alike”). The next time you think about that visit or go back to Amiens, or another French cathedral, that disposition comes bubbling to the surface, like an image that appears on a photographic plate when it is exposed to chemicals.

Activities of the mind: Awareness, attention, and recognition

Creating a memory begins with having a perception—which can be

associated with any or all of the senses—of an event or object

in your environment. There are three stages in forming a perception.

The first stage is to be aware of an object or something happening (e.g.,

another car appears at an intersection as you are driving down the street).

Next, you need to turn your attention to the object or event (e.g., you

are slightly aware of many things happening around you as you drive down

the street, but you seldom pay attention to them until something causes

you to do so). The third stage, which is crucial to having a perception,

is to recognize the object or event to which you have turned your attention.

Recognition is a complex activity of the mind-brain interaction that depends on your memory of having had an experience or been aware of such an object previously.

This three-stage process of awareness, attention, and recognition can happen while you are awake and acting in the world, but it can also happen when you are dreaming, or sometimes it can happen when you are hallucinating (defined as an apparent perception of an external object when no such object is present). There are also illusions, defined as the misinterpretation of a real stimulus.

What does this have to do with being an architect?

What does this have to do with being an architect?

Imagine that you are being interviewed for the design of a church by

a person whose only exposure to churches since his childhood has been

of traditionally designed buildings. When you show this person your

design for a contemporary church, you should not be surprised to find

a response like, “That doesn’t look like a church.” It’s

not that he is insensitive to good design, he simply has no basis in

his experience with which to understand what you consider to be good

design. In your case, once you go through six years of design studio,

you have a large number of dispositions based on the experience of

contemporary architecture, and almost all of them are tied to the visual

cortex. The fact that architecture competitions are based almost exclusively

on photographs of buildings is one of the results of this conditioning.

Let’s return to the Cathedral at Amiens. After you have entered through the narthex and moved into the huge cavern of the nave, you likely will become aware of stained-glass windows on both sides. If you turn your attention to one of the windows, you may recognize a depiction of Jonah and the whale. But you have to know the Bible story of Jonah being swallowed by a whale to be able to recognize this depiction. However, you might have an illusion: You look at the depiction of Jonah and think you see Moses walking into a cave on Mount Sinai. Or worse, you might hallucinate and imagine there is a real whale in the side aisle of the cathedral, causing you to run away. (This hallucination is not likely to happen to anyone with a healthy mind, although it is not uncommon for elderly people to believe they are hearing music when no one else is hearing anything.)

That evening, after you have been asleep for several hours, you will begin to dream. Most of the things you experience in your dream will vanish before you wake up. However, if your mind-brain has produced an experience of a whale trying to swallow you, you may wake up in a panic before you realize that it was your earlier perception of the stained-glass window that precipitated this sequence in your dream.

I hope you are beginning to “get the picture” (something you do in your mind’s eye, by the way) that what architects design does make a difference to the people who use or visit our buildings. The knowledge being generated in the neurosciences is going to provide another sea-change in practice, but it won’t happen overnight.

Seedtime and harvest in the orchards of knowledge

If you want to grow fruit, you must carefully prepare new ground; remove

old growth and underbrush, till and rake the soil, plant the seeds

and nurture them, provide water in adequate amounts, while the sun

provides ultraviolet and infrared rays creating a warm environment.

Through long hours of labor and required intervals of germination,

a new young tree emerges. Eventually this tree will bear fruit to reward

those who have labored in the orchard.

It would be foolish to chide those who are preparing the soil and planting the seed because there is no fruit—yet. It would be unwise to water too much or allow the sun to parch the land. When the time has come, the fruit will be ripe and its substance will sustain those who harvest it.

So it is with knowledge.

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

![]()