06/2005

AIArchitect spent an hour with John Paul Eberhard, FAIA, to ask him to synopsize his life to date and where it is going next. Following is his narrative of a handful of highlights of his 78 years and where his indefatigable energy will take us next.

How would you describe yourself?

How would you describe yourself?

One of the things I do these days, in deference to a great man now recently

deceased, is to use my original name, John Paul, which is what I went

by until I went off to the Marine Corps at 18. My sisters and brothers

still call me that, in fact. It’s one word, JohnPaul.

As the oldest of seven children, I have always been in charge of things. Moreover, in all of my nine careers, I have been responsible for putting together a new organization with a new mission that hadn’t existed before. So I would describe myself in short as an organizational entrepreneur. That ranges from starting a new school of architecture in Buffalo to starting a new institute for applied technology at the National Bureau of Standards and from creating a research program at the Sheraton Hotel Corporation to the most recent events, which include working with the San Diego Chapter of the AIA and establishing the new Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture.

Describe how the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture came to be.

That happened, initially, because Jonas Salk had stimulated Norman Koonce

and Syl Damianos [then president and chairman of the American Architectural

Foundation, respectively] to get someone to explore the brain’s

role in how architecture affects human experience. What Salk said was “Architects

should have a better understanding of human experience with architectural

settings.”

With that as a purpose, I came to the American Architectural Foundation

in 1995 as the “director of discovery.” Then I got exposed,

almost by accident, to the 1972 Nobel Laureate in medicine, Dr. Gerald

Edelman at the Neuroscience Institute. It was while reading one of his

books that I had my “ah-ha” experience: “Wow. This

really is a body of knowledge that could be of value to architects.”

With that as a purpose, I came to the American Architectural Foundation

in 1995 as the “director of discovery.” Then I got exposed,

almost by accident, to the 1972 Nobel Laureate in medicine, Dr. Gerald

Edelman at the Neuroscience Institute. It was while reading one of his

books that I had my “ah-ha” experience: “Wow. This

really is a body of knowledge that could be of value to architects.”

My previous careers were almost all heading research efforts, which prepared my brain to recognize the value of this new knowledge of how the brain works. By 2003, when the San Diego Chapter began their efforts to create an AIA Convention Legacy Project, I was pretty much up the curve in terms of understanding neuroscience; probably the only architect at that time who was. So it was a natural fit.

Who

is catching on to this idea?

Who

is catching on to this idea?

Having spent two years now as a Latrobe Fellow of the AIA College of

Fellows and had a wide exposure to neuroscientists, architects, and

people who are at the interface, my conviction is that there is an

enormous body of knowledge emerging in the neuroscience community that

has the potential of being extremely valuable to anybody who’s

engaged in the design of activities for humans. But my caveat is that,

possibly, architects, as they are presently educated and see themselves,

are going to have a hard time making the transition to a base of knowledge

in neuroscience. And that’s why I’m working hard and will

be working even harder in the next six months on finding support for

new doctoral programs at universities across the country that will

create interdisciplinary programs between architecture and neuroscience.

The University of Michigan is already interested, but doesn’t have the money to support such a program yet. Texas A&M is interested and has produced at least one person who will be working with us who came out of their architecture program. University of Minnesota Dean of Architecture Tom Fisher is interested.

What about the neuroscientists?

We haven’t gotten the interest on the neuroscience side of this

fence yet, which goes to the other caveat I have. The neuroscience community

is intrigued when they hear about the idea of looking at architecture

as a discipline that they might integrate with. But they fall into two

broad categories of resistance.

One

is the natural inclination of almost all non-architects to think that

what architects do is purely aesthetic, and they can’t imagine

that they’re ever going to be able to figure out how the brain

responds to aesthetics. So as intriguing as they might find the concept,

they are not clear on how in the world anybody would go about studying

it scientifically. What I try to point out when I can is that architects

are involved in a whole spectrum of attributes of buildings beyond aesthetics—like

light, temperature control, and acoustics. Then they begin to understand

that there might be something to quantify.

One

is the natural inclination of almost all non-architects to think that

what architects do is purely aesthetic, and they can’t imagine

that they’re ever going to be able to figure out how the brain

responds to aesthetics. So as intriguing as they might find the concept,

they are not clear on how in the world anybody would go about studying

it scientifically. What I try to point out when I can is that architects

are involved in a whole spectrum of attributes of buildings beyond aesthetics—like

light, temperature control, and acoustics. Then they begin to understand

that there might be something to quantify.

The next problem for the neuroscientists is that they are already very busy doing what they are already doing and have all of the support they need. So they are understandably reluctant to start a whole new subject. That’s why I am working to get neuroscientists while they’re PhD candidates and are looking for support. When I get the necessary funds to support PhD-candidate study, then I can inveigle them into exploring this subject in a way that would be useful but that they might not have done on their own without being inveigled. We have a lot of hypotheses that have come out of the workshops we’ve had to date that could become subject matter for doctoral theses.

Do you identify more with the neuroscientists or the architects in your

current efforts?

I think I see both sides of the street, so to speak. And the issue that

I’m interested in is in the middle: How do you bring the two notions

together? And, of course, you have to be careful in a question like that,

which implies that architects work only from the aesthetic side of the

brain. Although that’s partially true, architects are also businesspeople

and left-brain thinkers able to take descriptions for heating, ventilating,

air conditioning, structural design, and all of the other things that

came out of physics in the 19th century and convert them into a set of

working drawings.

Could you comment on the workings of the brain during such complex problem

solving?

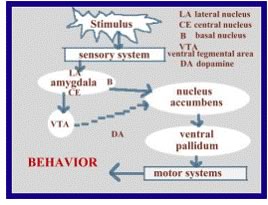

One of my ex-colleagues at Carnegie Mellon University, Nobel Laureate

Herb Simon, spent a good deal of his career studying how you become expert

in any field. He knew from his scientific background that our hippocampus

in the brain is able to move chunks of information, for instance, a piece

of a telephone number. It can move seven of those chunks at a time and

place it in long-term memory, which takes about five seconds. His analysis

was that to become an expert—no matter whether playing a violin,

bridge, or pool—you need about 50,000 chunks of information stored

in your brain and, given the hippocampus as the mechanism for doing it,

it took 10 years for that to happen. So his conclusion was that one did

not become an expert in any field in less than 10 years.

He

particularly got interested in architects because he looked at the complexity

of bringing together one’s creative and analytical abilities

to derive an abstract representation of physical space within the imagination.

He concluded that there is no way the human brain can simultaneously

hold all of that information in what’s called working memory, which

is in the frontal lobe. So what an architect becomes expert in is not

having all those things stored in their brain, but having a process stored

that enables them to go about assembling that information, and they need

an external storage medium—for instance, a piece of paper—, to

convey the results of that process.

He

particularly got interested in architects because he looked at the complexity

of bringing together one’s creative and analytical abilities

to derive an abstract representation of physical space within the imagination.

He concluded that there is no way the human brain can simultaneously

hold all of that information in what’s called working memory, which

is in the frontal lobe. So what an architect becomes expert in is not

having all those things stored in their brain, but having a process stored

that enables them to go about assembling that information, and they need

an external storage medium—for instance, a piece of paper—, to

convey the results of that process.

They may get The Big Idea about how these things could all be assembled into a building, but they’ve got to get that done on a piece of paper, as long-term storage, and then go back into their brains and begin to look at some other questions about the space, like the lighting, heating and air conditioning, or the structural design, and they may bring in other people who are experts to help them with that process. But it’s the process of taking the brain’s expertise stored in those 50,000 chunks that architects acquire as they practice and go to school—although I think more in practice than in school.

You are also a noted artist with a crisp, distinctive style that came

to you relatively late in life. Could you compare that to your discussion

of developing expertise?

I used to tell my students that in my observation, without strong evidence,

what you’re doing at 30 years old is essentially what you’ll

be doing for the rest of your life. You may change organizational context,

but you’re not going to become a Bill Gates at 35 if you haven’t

shown that inclination by the time you’re 30. And I think that’s

also true of artistic inclination. If you haven’t shown any ability

to paint, write music, or whatever before you’re 30, the probability

that when you are all of a sudden going to acquire this talent at 40

isn’t very high. In my case, I tried to play the clarinet, and

I never got anywhere with it. Lois, my wife, can play the piano, and

I would play a fumbling duet with her, but I never got good enough to

do anything.

I

made some drawings for architecture class at university. And, of course,

in my very first career, I designed a hundred churches, so I did a lot

of drawing for those, but those were architectural renderings, not the

ones that I do now.

I

made some drawings for architecture class at university. And, of course,

in my very first career, I designed a hundred churches, so I did a lot

of drawing for those, but those were architectural renderings, not the

ones that I do now.

So why, in 1984, when I was 57, did I all of the sudden decide to start making the drawings that I’ve been able to make ever since, without any getting ready or practicing? I have no idea. And the only hypothesis could be that it’s like architectural design solutions that seem just to come to you, subconsciously, my brain was working on putting that style together, and, for whatever reason, in 1984, it just came to fruition.

Can you see yourself retiring?

One of my board members refers to me as the Energizer Bunny—which

is a genetically fortunate event for me, because I don’t have

any special reason why I should be filled full of energy and able to

work at this point in my life other than I was born with the right genes.

But, interesting enough, as a sideline, I also owe a lot, for whatever

reason, to the Marine Corps. When I got drafted into the Marine Corps,

I weighed 135 pounds at six feet. So I was really skinny. And I had been

sick all of my life—I had rheumatic fever twice when I was a teenager,

and always had respiratory problems. I came out of boot camp weighing

154, and I’ve never been sick a day in my life since then. After

I got out of boot camp in 1945, the war in Japan was over. But the Marines

were still fighting with Chiang Kai-shek. Everybody else in my platoon

went off to China to fight, and I got left behind to be the so-called “education

officer” at Parris Island, even though I was a buck private. But

that’s where my brain came in.

But, interesting enough, as a sideline, I also owe a lot, for whatever

reason, to the Marine Corps. When I got drafted into the Marine Corps,

I weighed 135 pounds at six feet. So I was really skinny. And I had been

sick all of my life—I had rheumatic fever twice when I was a teenager,

and always had respiratory problems. I came out of boot camp weighing

154, and I’ve never been sick a day in my life since then. After

I got out of boot camp in 1945, the war in Japan was over. But the Marines

were still fighting with Chiang Kai-shek. Everybody else in my platoon

went off to China to fight, and I got left behind to be the so-called “education

officer” at Parris Island, even though I was a buck private. But

that’s where my brain came in.

I was in the Marine Corps for two and a half years, and then I was a Midshipman for a year and then I got married, and you can’t be married and a Midshipman. So I was let out. But I kept thinking, one of these days the Marine Corps might decide that I still owe them some more time, although by now it’s a little late.

But to answer your question, I don’t know what I’d be like if I sat around the house and did nothing all day, or just played tennis. So you could say that opening up our ANFA Washington office now is still another career move. It’s really a continuation of the Academy and what we’re doing there.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

To

learn more about the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture,

visit their Web site. Read Eberhard’s Latrobe Fellowship White paper

|

||