12/2005

A tale of conception, perception, and proprioception

John

P. Eberhard, FAIA

John

P. Eberhard, FAIA

President, Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture

Neuroscientists say that we have both a primary consciousness and a higher-order consciousness. It is higher-order consciousness that makes humans unique. It enables us to think about the past, contemplate the future, and to be conscious of being conscious in the present. Beloved 19th century author Charles Dickens would have had no knowledge of neuroscience, but his intuitive understanding of the mind and how it functions—specifically for archetypal Ebenezer Scrooge in A Christmas Carol—makes it possible for Scrooge to “see” or better to “experience” the presence of three spirits from the past, the future, and the present.

Creating visual images

Early in the story, Scrooge has this conversation with the ghost of his

former partner, Jacob Marley:

“You don’t believe in me,” observed the Ghost.

“I don’t,” said Scrooge.

“What evidence would you have of my reality beyond that of your senses?”

“I don’t know,” said Scrooge.

“Why do you doubt your senses?”

“Because,” said Scrooge, “ a little thing affects them.”

(He means food or drink.)

Dickens “paints” word pictures of places that, with a bit

of imagination, our brains can as easily transform into visual images.

This is the same process as might be done with drawings, through which

someone else provides us with an image from his or her imagination).

Dickens “paints” word pictures of places that, with a bit

of imagination, our brains can as easily transform into visual images.

This is the same process as might be done with drawings, through which

someone else provides us with an image from his or her imagination).

“He lived in chambers which had once belonged to his deceased partner. They were a gloomy suite of rooms, in a lowering pile of building up a yard, where it had so little business to be, that one could scarcely help fancying it must have run there when it was a young house, playing at hide-and-seek with other houses, and forgotten the way out again. It as old enough now, and dreary enough, for nobody lived in it but Scrooge, the other rooms being all let out as offices. The yard was so dark that even Scrooge, who knew its every stone, was fain to grope with his hands. The fog and frost so hung about the black old gateway of the house, that it seemed as if the Genius of the Weather sat in mournful meditation on the threshold.”

Perception, conception, and proprioception

The left hemisphere of our brain is involved in “perception”: we

see an object or hear a sound and we recognize it. The right hemisphere

deals with “conception”: for example, the image we need to

form to make a drawing. Materials provided from the outside world by

our perceptions can form conceptions, or they can be formed from the

stuff of our imagination inside our heads.

When Dickens tells us that Scrooge “who knew its every stone,

was fain to grope with his hands” he is explaining an experience

we all have had. When you grope in the dark (for example, if you get

up in the middle of the night and don’t want to turn on the light

because it will wake your spouse), you find your way by using information

you have stored in your spatial memory using your eyes, but now recall

with your sense of touch and your sixth sense called proprioception. This sixth sense makes you aware of where your body is in space and enables

you to find your way in a familiar place without using your eyes.

When Dickens tells us that Scrooge “who knew its every stone,

was fain to grope with his hands” he is explaining an experience

we all have had. When you grope in the dark (for example, if you get

up in the middle of the night and don’t want to turn on the light

because it will wake your spouse), you find your way by using information

you have stored in your spatial memory using your eyes, but now recall

with your sense of touch and your sixth sense called proprioception. This sixth sense makes you aware of where your body is in space and enables

you to find your way in a familiar place without using your eyes.

Parts of the brain work together

The description of Scrooge’s old school (from the past) is pictured

with Dickens’ words:

“They soon approached a mansion of dull red brick, with a little weathercock-surmounted cupola, on the roof, and a bell hanging in it. It was a large house, but one of broken fortunes; for the spacious offices were little used, their walls were damp and mossy, their windows broken, and their gates decayed. Fowls clucked and strutted in the stables; and the coach-houses were over-run with grass. Nor was it more retentive of its ancient state, within; for entering the dreary hall, and glancing through the open doors of many rooms, they found them poorly furnished, cold and vast. There was an earthy savor in the air, a chilly bareness in the place, which associated itself somehow with too much getting up by candle-light, and not too much to eat.”

Dickens is also skilled at using analogies—concepts we understand

to suggest a way of looking at (or understanding) things we haven’t

experienced before. For instance, when he suggests “too much getting-up

by candlelight,” we recall that he is talking about a period of

time before there was electricity, when a schoolboy was required to get

up very early, before the sun rose.

Dickens is also skilled at using analogies—concepts we understand

to suggest a way of looking at (or understanding) things we haven’t

experienced before. For instance, when he suggests “too much getting-up

by candlelight,” we recall that he is talking about a period of

time before there was electricity, when a schoolboy was required to get

up very early, before the sun rose.

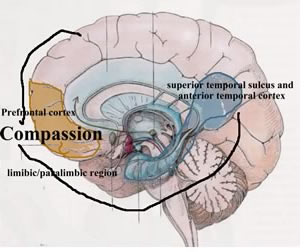

Research professionals in the neuroscience field have made rapid progress over the past 20 years in understanding how certain areas of the brain interact to produce emotions. Scrooge offers us a good case study:

- When Scrooge recognizes his old neighborhood, his prefrontal cortex (see diagram) provides his experience.

- When he recognizes his old school and the associated memories, his superior temporal sulcus and anterior temporal cortex provide this information.

- When he experiences sadness and anxiety, it is the limbic region that is activated.

In the end of the story, Dickens says of Scrooge,

“It was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge. May that be truly said of us, and all of us! And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God bless Us, Every One!”

I join him in wishing you a happy holiday season and a blessed New Year.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()