7/2006

A midsummer night’s article

by John P. Eberhard, FAIA

Founding president, Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture

You can’t really remember anything in your life that happened before you were three years old, except things that other people have told you. Perhaps that’s why early childhood (from three to six years old) seems so cloaked in mystery. At age three, whether you are flying with Peter Pan, making drawings of monsters and castles, or explaining your big secret to your best little friend (whom no one else can see), you are using your brain to shape your mind’s experiences.

Do you remember the passage in Peter Pan when Wendy asks Peter about how fairies came to be? Peter responds, “You see, Wendy, when the first baby laughed for the first time, its laugh broke into a thousand pieces, and they all went skipping about, and that was the beginning of fairies.”

What

a wonderful appeal to young children! They don’t need a picture

to see the fairies; they can use their imagination. A young brain has

no capacity to move any of the child’s early experiences into long-term

memories—at least that’s what neuroscience research tells

us. Among the large number of mysteries of the mind that are still unresolved

by neuroscience is this question of “temporal memory”—how

do we know when something happened?

What

a wonderful appeal to young children! They don’t need a picture

to see the fairies; they can use their imagination. A young brain has

no capacity to move any of the child’s early experiences into long-term

memories—at least that’s what neuroscience research tells

us. Among the large number of mysteries of the mind that are still unresolved

by neuroscience is this question of “temporal memory”—how

do we know when something happened?

Myths of childhood

Three common myths young children believe (because their parents say

they are true), that they no longer believe by age of seven or eight,

are:

- Santa Claus delivers presents to all good boys and girls in one night, knows where every child lives, comes down a chimney (even if there is none), lives at the North Pole, has a sleigh pulled by reindeer who can fly, and stays the same age forever.

- The Easter Bunny delivers treats including colored Easter eggs and jellybeans on Easter morning for good children.

- The Tooth Fairy visits the child’s bedroom during the night and leaves coins in exchange for a tooth left under the pillow.

Variations on these myths are essentially found everywhere in the world.

This is another indication that children’s brains are essentially

the same, regardless of where they are born and raised. Before they turn

seven, children everywhere believe in one or all of these myths. After

they turn seven or eight, they can no longer accept the truth of these

myths. Many adults remember clearly for their whole lives when and how

they discovered the truth. However, many adults would still like to believe

that there is a Santa Claus.

Variations on these myths are essentially found everywhere in the world.

This is another indication that children’s brains are essentially

the same, regardless of where they are born and raised. Before they turn

seven, children everywhere believe in one or all of these myths. After

they turn seven or eight, they can no longer accept the truth of these

myths. Many adults remember clearly for their whole lives when and how

they discovered the truth. However, many adults would still like to believe

that there is a Santa Claus.

The wisdom of Fred Rogers

Fred Rogers, who died in 2003, was for more than 30 years the creator/host

of the children’s program Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. He knew well how to talk to young children about their fears—going

down the bathtub drain or stepping on someone’s shadow—because

he was wise in the ways that children believe and in the things they

imagine. He advised parents to be aware that:

- Imaginary friends can play an important role in the lives of children, allowing them to fulfill wishes through their imaginations, including having friends or siblings to assuage loneliness, or scapegoats who made their messes. “Imaginary friends usually play a brief role in a child's life,” Rogers wrote. “They usually go away as quickly as they arrive. But while they are there, they often provide the companionship and support many children feel they need.”

- Children’s imaginations are engaged by almost everything they see, from an empty box to a large spoon.

- Secrets often hold a great appeal for children, because they can give a child a feeling of holding something all to oneself.

- Children express their creativity by making or doing. Painting a picture, completing a project, and building a block city all require creative problem solving. Feeling good about things they have made can help children develop a sense of pride in themselves as unique and worthwhile individuals.

The remarkable house drawings of five-year-old children

The remarkable house drawings of five-year-old children

Here is another childhood mystery that is architectural in character.

If you have saved drawings made by your children, or if your parents

saved drawings you made as a child, look for a drawing of a house done

when you or your child was five years old. I can be quite certain that

it will look something like the drawing on the left, which my son Richard

produced when he was five. On the right is a drawing of the house in

Winchester, Mass., in which we lived at the time.

The mystery part is that all five-year-old children draw the same house

as Richard did, even though seldom does their actual home look anything

like their drawings. For example, on the left below is a drawing by a

five-year-old who lives in Israel; on the right is the house he lives

in.

The mystery part is that all five-year-old children draw the same house

as Richard did, even though seldom does their actual home look anything

like their drawings. For example, on the left below is a drawing by a

five-year-old who lives in Israel; on the right is the house he lives

in.

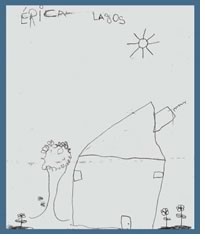

Pictures from Spain

After the civil war in Spain, the Spanish Child Welfare Association of

America asked children to make drawings as a form of therapy. Aldous

Huxley, who organized a publication of these drawings called “They

Still Draw Pictures,” for American Friends Service Committee

in 1938, said, “To a sense of color children add a feeling for

form and a remarkable capacity for decorative invention. Many of these

landscapes and scenes of war are composed according to the most severely

elegant classical principles. Voids and masses are beautifully balanced

about the central axis. Houses, trees, figures are placed exactly where

the rule of the Golden Section demands that they should be placed.”

Below are two of the drawings. The children did not live in such houses.

Below are two of the drawings. The children did not live in such houses.

A few years ago, I was challenged to obtain some drawings from children who live in Africa in small villages consisting of round huts with straw roofs. My daughter Carol, who visited Mozambique as a State Department employee, was able to visit such a village and obtain the following drawing from a five-year-old girl who lived there. Notice how much this drawing made in 2001 shows a house like the one drawn by the Spanish child in 1938.

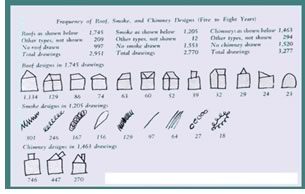

Rhoda Kellogg examined a million drawings done by young children and

published her findings in Analyzing Children’s Art (National Press,

1970). These drawings represent the work of an estimated 10,000 children

aged four to eight years. They are mostly from California, but she also

obtained drawings during visits to places such as London; Paris; Amsterdam;

Gotenberg, Sweden; and Stockholm—a total of 5,000 drawings from

30 countries. Buildings are drawn by young children, Kellogg suggests,

by combining diagrams in various ways, not as the result of observing

houses on the street. These basic diagrams include: the rectangle, oval

(including circles), triangle, Greek cross, the diagonal cross, and a

catchall shape she calls the odd shape. The child artist has only four

groups of subjects: animals, buildings, vegetation, and transportation.

Rhoda Kellogg examined a million drawings done by young children and

published her findings in Analyzing Children’s Art (National Press,

1970). These drawings represent the work of an estimated 10,000 children

aged four to eight years. They are mostly from California, but she also

obtained drawings during visits to places such as London; Paris; Amsterdam;

Gotenberg, Sweden; and Stockholm—a total of 5,000 drawings from

30 countries. Buildings are drawn by young children, Kellogg suggests,

by combining diagrams in various ways, not as the result of observing

houses on the street. These basic diagrams include: the rectangle, oval

(including circles), triangle, Greek cross, the diagonal cross, and a

catchall shape she calls the odd shape. The child artist has only four

groups of subjects: animals, buildings, vegetation, and transportation.

This

seems to be a mystery worthy of exploration by the neuroscience community.

This

seems to be a mystery worthy of exploration by the neuroscience community.

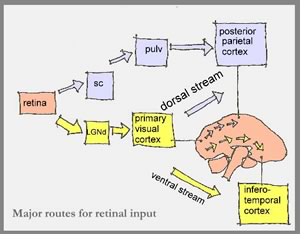

A possible neuroscience explanation

Melvin A. Goodale, in “Perception and Action in the Human Visual

System,” in The New Cognitive Neurosciences (second edition, MIT

Press, 2000), explains that neuroscience research has shown that control

of skilled actions (such as drawing) depends on visual processes that

are quite independent from those that lead to knowledge based on our

perception of the world. Moreover, this distinction between vision for

perception and vision for action is reflected in the organization of

the visual pathways in the cortex (the outer layer of the brain that

looks like cauliflower). There

are two “streams” that flow

from the primary visual cortex: a ventral stream and a dorsal

stream (named after their anatomical location in the brain).

Each stream uses this visual information in different ways. The ventral

stream transforms the visual information into perceptual representations

that embody the enduring characteristics of objects and their relations.

Such representations enable us to identify objects, attach meaning

and significance to them, and establish their causal relations—operations

that are essential for accumulating knowledge about the world—e.g., “This

is Amiens Cathedral.” In contrast, the transformations carried

out by the dorsal stream deal with moment-to-moment information about

the location and disposition of objects with respect to stimulating

a response—e.g., from the muscles being used to control skilled

actions directed at those objects (such as making a drawing). Both

streams work together in producing a behavioral response.

Each stream uses this visual information in different ways. The ventral

stream transforms the visual information into perceptual representations

that embody the enduring characteristics of objects and their relations.

Such representations enable us to identify objects, attach meaning

and significance to them, and establish their causal relations—operations

that are essential for accumulating knowledge about the world—e.g., “This

is Amiens Cathedral.” In contrast, the transformations carried

out by the dorsal stream deal with moment-to-moment information about

the location and disposition of objects with respect to stimulating

a response—e.g., from the muscles being used to control skilled

actions directed at those objects (such as making a drawing). Both

streams work together in producing a behavioral response.

The division of labor between the two cortical visual pathways requires that different transformations (changes in the kinds of signals used by the brain) be carried out on incoming visual information.

Vision for perception and vision for action

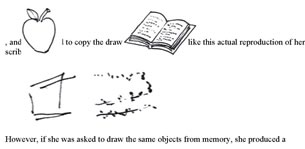

Here is a case history example how these two streams perform.

A woman suffered irreversible brain damage as a result of overexposure

to carbon monoxide when she was 34. When she regained consciousness,

she was unable to recognize the faces of relatives and friends or identify

the visual forms of common objects. She could not even tell the difference

between a square and a triangle. Yet, she could recognize people by their

voices and objects by feeling their shapes. In other words, her damage

was exclusively visual. Ten years later, when she was shown a drawing

of an apple or a book, such as the one below, she could not identify

the objects.

A woman suffered irreversible brain damage as a result of overexposure

to carbon monoxide when she was 34. When she regained consciousness,

she was unable to recognize the faces of relatives and friends or identify

the visual forms of common objects. She could not even tell the difference

between a square and a triangle. Yet, she could recognize people by their

voices and objects by feeling their shapes. In other words, her damage

was exclusively visual. Ten years later, when she was shown a drawing

of an apple or a book, such as the one below, she could not identify

the objects.

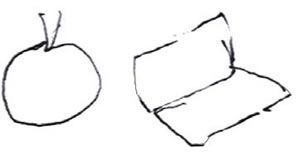

However, if she was asked to draw the same objects from memory, she

produced a respectable representation of both items—like these

actual reproductions of what she drew, below—but later she could

not identify her own objects.

However, if she was asked to draw the same objects from memory, she

produced a respectable representation of both items—like these

actual reproductions of what she drew, below—but later she could

not identify her own objects.

Her inability to perceive the shape and form of objects in the world was due to deficits in basic sensory processing. She remained able to identify colors. Her deficit seems to have been “perceptual” rather than “sensory” in nature. She simply could not perceive shapes and forms, even though the early stages of her visual system would appear to have had access to the requisite low-level sensory information. She can use visual information about the size, orientation, and shape of objects to program and control her goal-directed movements (such as drawing from memory), even though she has no meaningful perception of those object features.

This may explain why a five-year-old child draws a house that has no resemblance to the one in which he or she lives. The five-year-old brain is still developing, and the “corpus callosum,” which connects the perceptual apparatus of the brain to the muscle controls of drawing is not yet fully developed. The child, therefore, is like the woman described above in the sense that he or she cannot draw something perceived in the outer world. However, when an image of “house” is called up from memory, a reasonable representation of the image can be drawn. Exactly why every child in the world draws this same house is still a mystery.

Before any child is five years old, he or she will develop the following capacities: Telling the difference between appearance and reality, visual perception, identifying the sources of various stimuli (where the music is coming from), cause and effect, in what order things occur, what certain things are used for (a spoon to eat cereal, a coat to keep warm), etc. The country or cultural context into which the child is born has little or no impact on how these developments are produced by the brain. Because there is no difference among children in these capacities and no difference in how their brain is pre-programmed to learn a language, perhaps the brain has evolved with an image of a house that is the same for all of us.

Final word from science

In their book The Learning Brain (Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford,

2005), Sarah-Jayne Blakemore and Uta Frith point out that “scientists

now know a considerable amount about learning—how brain cells

develop before and after birth; how babies learn to see, hear, talk,

and walk; how infants acquire a sense of morality and social understanding,

and how the adult brain is able to continue learning and growing. What

amazed us was, despite this growing body of knowledge and its relevance

to education policy, how few links exist between brain research and

education policy and practice.”

One could say the same thing about how few links exist between brain research and architecture.

And, a final thought from my friend Fred Rogers (in whose real Pittsburgh neighborhood I lived for six years while heading up Carnegie Mellon University’s architecture department). Mr. Rogers believed that a secure and happy childhood was of the greatest importance not because we stay children forever, but because we don’t.

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

For more information, visit the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture Web site.

Read the other six articles in this series:

• You Need to Know What You Don't Know

Read Story

• Thanks for the Memories

The brain, the mind, and creation of memories

• See the Space and Hear the Sound of Music

How we use the brain and mind to see and hear

• How We Use the Brain and Mind to Smell, Taste, and Touch

Read

Story

• Health-Care Facilities and Neuroscience Knowledge

Read

Story

• Children’s Brains Are the Key to

Well-Designed Classrooms

Read

Story

Read this introductory article by the author:

The Neuroscience in A Christmas Carol

A tale of conception, perception, and proprioception

![]()