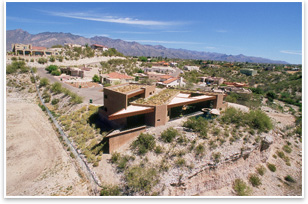

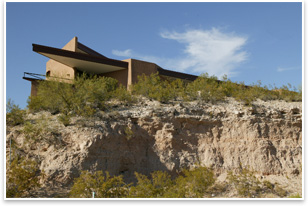

| Riverfront Residence: Greening the Desert What’s a bit of green roof experimentation between friends? How do you . . . design a house with a green roof in an irregular desert site? Summary: Several years ago, architect Bil Taylor designed and built a 3,800-square-foot house in a small lot next to a river. As if the challenging conditions weren’t enough—a cliffside site, the hot climate of the Sonoran Desert, the size and shape of the lot, and what the architect considered a modest budget—Taylor decided the house would also have the first modern desert roof garden in the U.S.  The Riverfront Residence at night. A cliff, a river, a small site McKenzie thought the search for a lot would take a few years. Taylor found it right away–a small cliffside lot with great views, right next to the Rillito River. And right away, too, the two friends started discussing design. “I gave him three things,” says McKenzie. “I wanted a house to surround a patio and a swimming pool, a wing to myself, and lots of guest rooms far away from my wing.” Taylor explains that, at least in the Southwest, custom homes are usually built on larger lots. He ended up building a 2-story home, also “less than normal” in the Tucson area, he says, to accommodate the program.  The house is shaped like a backwards Z. Fitting an ambitious program into a small lot was not the only challenge. Taylor also had to stay away from the erodable cliffside edge and deal with the harsh climate conditions of the region. On the plus side, the lot offered both expansive views and more intimate views to people and wildlife on the riverwalk just below it. Overall, Taylor thought of the site as “restrictive and exciting.” Taylor says McKenzie is “the definition of the ideal client.” He gave the architect a clear program and room to create a Modern design, which was the architect’s natural preference. Taylor did, however, have to stay within what he calls McKenzie’s “Scottish budget” (which ended up being about $640,000 back in 2001), but he gladly took on the challenge. From “U” to “Z” Beyond the particularities of the site and the program, the hot, dry climate in the desert had a strong influence on the design. A variety of weather conditions in the area demanded a very thoughtful approach to outdoor spaces. Taylor explains that shade is critical to outdoor summer living, and even during the winter months. At the same time, rain is also a factor to consider.“Rain is a blessed and rare event that is celebrated,” says Taylor. “People like to sit outside and watch it.”  The Riverfront Residence’s green roof. Taylor’s solution was an L-shaped first floor house plan that formed a protected outdoor space. A 30- to 60-degree triangular roof form overlay created a large patio, and the west side point became a sunset patio that both architect and client now refer to “the Leonardo DiCaprio point,” a nod to the setting of the famous scene in the film “Titanic” depicting DiCaprio leaning over the bow of the ship. The house is not only open to the outdoors, but in many ways the outdoors is a continuation of the adjacent indoor living space. The flooring and ceiling materials used inside continue through the floor-to-ceiling glass curtain wall onto the large patio. The patio provides a generous shaded area with a great panoramic view; light comes in through a triangular hole, which also accommodates a fruit tree. In addition to the “Leonardo” deck—great for cocktails, the client says—the client’s favorite feature of the house is a fireplace open on three sides that serves a family room on one side and a reading room on the other. Notoriously absent among McKenzie’s favorite house features is the garden roof, but he’s had a hands-off approach to it from the start. “I would listen to them and say, ‘fine, do what you want’,” he says, referring to the process the design team went through to create the roof.  A dramatic cliff overlook. Located above the heated and cooled areas of the house, not on the patio roofing, the garden functions as a microshading device in the hot desert climate. The green roof provides a nice view to several second-floor bedrooms, and one of them actually opens onto it. McKenzie has no way of estimating cost-savings associated with having the roof, but he says the house is remarkably warm in the winter, and that he rarely uses the heater. A garden in the desert The question, of course, was how to make that happen in the desert. Costs would be high, which was the client’s concern, and Taylor imagined it would also be a hassle. Taylor gives project architect Chris Evans credit for having had the foresight and taken the initiative to contact the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) to request a grant. The ADEQ approved the application and agreed to fund the garden as a demonstration project to mitigate run-off, reduce the heat-island effect, and control erosion, all of which are of concern to the department. The grant turned an otherwise costly idea into a palatable proposition for the client, so McKenzie agreed to give the garden roof a try. Taylor says this was the first desert roof garden in Arizona. He adds, his firm “didn’t have a clue as to how to go about doing it.”  Interior views to the riverwalk beyond. Landscape architect Quetzalli Barholomaei, with Tucson-based Blue Mesa Studios, worked with Chris Evans to design a first experimental attempt. The goal was to devise a way to cover the roof with dirt, irrigate the area, and keep plants alive in that environment. All of that required a strong, leakproof roof structure and careful plant selection. In addition to the composition of the soil mix, its depth and the plant palettes were key to the success of the garden. The lighter the soil mix, the better. The conflict, of course, is that a shallow (and lighter) soil will only allow certain kinds of plants to grow in the desert. “The trade-off between greater depth and weight is the final judgment call,” says Taylor. The roof started out with about 25 different kinds of native flower and grasses, but only about 6 survived the shallow soil and windy conditions. Among the original plants were species such as blackfoot daisies, melampodium, a variety of yucca and some river edge planting. “All the plants were desert native, and all of them had to be in commercial production,” says landscape architect Bartholomei. “What we learned is that the grasses seem to be the best adaptive for this dryer environment.” Bartholomaei says some of the plants that eventually didn’t make it actually surprised her. She says she expected species such as creosote or brittle bush to make it, but they didn’t do well, and neither did other species that require a deeper soil. Concerning irrigation, Bartholomaei warns against thinking that desert gardens don’t use as much water as other types of gardens. “If you want to keep water use down, you have to use native plants,” she says. “But if you want them to look good, you have to use water.” She estimates a desert roof garden uses about as much water as residential planting of equal design, perhaps slightly more. But, she says, a low-water-use roof in the desert can be done, as long as it’s designed with indigenous plants. Taylor and his wife, Carole, ended up living in the Riverfront Residence for a while because McKenzie decided to postpone his retirement for a few years. Monitoring and maintaining the garden became their job and, eventually, their expertise. They now work with Jason Kopke, a landscape designer who came across the Riverside Residence while working on his master’s thesis in landscape architecture at the University of Arizona. At the time the garden needed attention, so Kopke decided to focus part of his thesis on the project and continues to study its evolution. “We’re always tweaking,” Kopke says. The experiments are aimed at figuring out how dry the soil can be, or what types of plants perform better under various conditions. The garden includes a control section that has never been touched except to remove some of the original plants that didn’t make it. Taylor says that, after seven years, the desert garden has achieved a kind of steady-ecosystem state. Today it has a mix of yellow and purple flowers and a few feathery grasses. Taylor describes the area as a “desert roof field” more than a garden. The architect is currently building his own house next to the Riverfront Residence, and it, too, will have a green roof. “The client is much harder to work with on this one,” he says, adding that his house will have the “new and improved” version of the garden. |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Kowaleski Residence: Three Views of a Family

› Against Interpretation

› Method Homes Pre-Fab Prototype Walk the Middle Path

See what the Small Project Practitioners Knowledge Community is up to.

See what else the Architects Knowledge Resource has to offer for your practice.

Photos Courtesy of Bil Taylor.