Louisiana Cancer Research Center Rises Above Post-Katrina New Orleans

Kept afloat after the storm delayed its completion, RMJM’s medical research lab welcomes in the entire city

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

How do you . . . design a medical research facility with a strong community and public presence? How do you . . . design a medical research facility with a strong community and public presence?

Summary: RMJM’s Louisiana Cancer Research Center provides public space for community groups with a human-scaled and glass-walled entrance lobby that works as a welcoming front porch. Its circulation patterns are meant to enhance collegial connections and stimulate the interaction of research and treatment. A repeated design theme is the lifting or floating of various volumes with cantilevers and transparencies.

View the photo gallery

Graphics courtesy of the architect.

1. The Louisiana Cancer Research Center.

2. The research centerís lobby.

3. Laboratories in the research center.

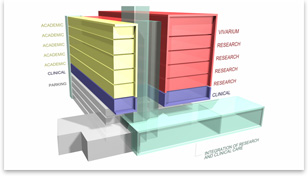

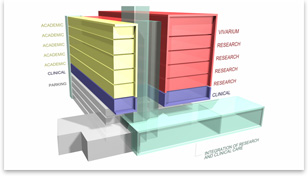

4. A programmatic diagram of the research center.

New Orleans’ Louisiana Cancer Research Center aims to be a community of healing in a city of hurricane-battered and neglected medical infrastructure. Located along Tulane Avenue, an east-west axis that links the Tulane University and Louisiana State University’s medical schools, the addition of the Research Center will add to the neighborhood of campuses. The same schools (along with Xavier University of Louisiana) commissioned the building and will use it for research.

Beyond the academic community formed by the building’s site, the research center’s design offers unique public spaces for a community still re-sorting their lives after Hurricane Katrina. Quite grimly, New Orleans needs this lab. Louisiana is the least healthy state in the nation overall and has the second highest rate of cancer deaths in the country, according to the New Orleans Times-Picayune.

Community healing

The RMJM-designed building’s front entrance faces north along Tulane Ave., while it’s longer, broader face to the east addresses Interstate 10. The laboratory expresses its volume as three, 10-story vertical sections that are sandwiched together. The two end volumes cantilever slightly over a long glass-walled lobby that extends to the west of the site beyond the footprint of the rest of the building. All three of these volumes represent specific programmatic divisions within the building. The east block contains academic offices, the middle block is a circulation core, and the west block houses lab and research functions. All three are clad in pristine, white metal panels, calling to mind the humanistic qualities of medical care and research: purity, renewal, and hope.

The entrance of the state-funded building addresses the street and the surrounding community at a human scale with a short set of stairs that leads up a plinth into a natural-light-bathed, double-height lobby and public meeting space. This framed box is supported by two sets of thin columns and covered in glass walls. Its use of glass creates a subtle illusion of floating for the lab sections above and also invites views into the lab and out to the neighborhood from a semi-public forum. In function and resemblance, this lobby is not unlike a residential front porch, appropriate to New Orleans’s unique culture of hospitality.

Steve McDaniel, AIA, of RMJM’s Philadelphia office, says the west section of this lobby can be used for medical researcher meetings or for community organizations, like support groups for cancer survivors and their families. Adding this kind of public space into research labs has become a trend in science facility design, as clients and architects have realized that regularly letting the community into their buildings raises any institution’s profile. “It’s a gesture not only to address the community architecturally, but also to let them use the building,” he says. Steve McDaniel, AIA, of RMJM’s Philadelphia office, says the west section of this lobby can be used for medical researcher meetings or for community organizations, like support groups for cancer survivors and their families. Adding this kind of public space into research labs has become a trend in science facility design, as clients and architects have realized that regularly letting the community into their buildings raises any institution’s profile. “It’s a gesture not only to address the community architecturally, but also to let them use the building,” he says.

Making connections

Inside, the lobby is a double-height space with terrazzo floors and an overhanging wood wall placed over the front desk to add textural warmth to the room. Researchers will enter their labs from the middle circulation core, which houses elevators and an open stairwell. The schools that are building the lab are also considering using one floor of the building for clinical patient care to facilitate “bench-to-bedside” treatments, as McDaniel says, with experimental drugs and therapies developed within the building. Patients being treated at the Research Center would be able to “look up the open stairway and see the researchers upstairs. So if you’re a patient, you’d feel like you’re in the best possible environment because you’d know you were in a research building,” he says.

The $65 million, 175,000-square-foot lab also intends to get its staff to connect with each other with a series of informal meeting spaces—another trend in contemporary lab design. Specifically, RMJM wanted to encourage more interaction between the professor-scientists camped out in their offices on one side of the building and the researcher graduate students toiling at their behest in the labs on the other side of the building. So McDaniel and his team placed small, informal meeting spaces in between the two camps’ strongholds. “Hopefully, that will encourage them to talk to each other and break down what I think is a natural barrier in medical schools between the professors and the medical students,” he says. “We can’t force them to talk to each other, but we’ve done everything we can to facilitate that.” The $65 million, 175,000-square-foot lab also intends to get its staff to connect with each other with a series of informal meeting spaces—another trend in contemporary lab design. Specifically, RMJM wanted to encourage more interaction between the professor-scientists camped out in their offices on one side of the building and the researcher graduate students toiling at their behest in the labs on the other side of the building. So McDaniel and his team placed small, informal meeting spaces in between the two camps’ strongholds. “Hopefully, that will encourage them to talk to each other and break down what I think is a natural barrier in medical schools between the professors and the medical students,” he says. “We can’t force them to talk to each other, but we’ve done everything we can to facilitate that.”

Lifting up

RMJM was hired for this project in 2004, but Hurricane Katrina delayed it and left its mark on its design as well. Code changes required that electrical and mechanical systems be lifted above the ground floor to avoid flooding. To accommodate this requirement, McDaniel and his team placed the equipment in found space on the fourth floor between the parking garage (which occupies the bottom four floors of the rear of the building) and the lab block, which was created by the slope of the parking garage floor.

Though it’s a mostly unseen technical detail, this motif of lifting masses above the floodplain is expressed again and again in several of the building’s details. For example, the front desk in the lobby is lifted up on legs, and the lobby and public space section cantilevers over the edge of the plinth it sits on. Though it’s a mostly unseen technical detail, this motif of lifting masses above the floodplain is expressed again and again in several of the building’s details. For example, the front desk in the lobby is lifted up on legs, and the lobby and public space section cantilevers over the edge of the plinth it sits on.

Lab spaces are open and flexible and can be expanded to change their function as grant money swells and recedes. (The lab is expected to be a federally funded National Institutes of Health facility.)

Construction will begin in March and is scheduled to be finished in late 2011. McDaniel says the research center will likely be the first new major construction project to begin in New Orleans since Hurricane Katrina. Although his medical research lab may not have the PR charm or design flash of Brad Pitt’s Make It Right Houses, Morphosis’ New Orleans National Jazz Center, or any number of high profile projects in the city, McDaniel says it can’t come together fast enough. “Seeing this start will be really important to the psychology of the city,” he says. “It’ll be a great symbol of hope.” |

How do you . . .

How do you . . .  Building Type Basics for Healthcare

Building Type Basics for Healthcare

The $65 million, 175,000-square-foot lab also intends to get its staff to connect with each other with a series of informal meeting spaces—another trend in contemporary lab design. Specifically, RMJM wanted to encourage more interaction between the professor-scientists camped out in their offices on one side of the building and the researcher graduate students toiling at their behest in the labs on the other side of the building. So McDaniel and his team placed small, informal meeting spaces in between the two camps’ strongholds. “Hopefully, that will encourage them to talk to each other and break down what I think is a natural barrier in medical schools between the professors and the medical students,” he says. “We can’t force them to talk to each other, but we’ve done everything we can to facilitate that.”

The $65 million, 175,000-square-foot lab also intends to get its staff to connect with each other with a series of informal meeting spaces—another trend in contemporary lab design. Specifically, RMJM wanted to encourage more interaction between the professor-scientists camped out in their offices on one side of the building and the researcher graduate students toiling at their behest in the labs on the other side of the building. So McDaniel and his team placed small, informal meeting spaces in between the two camps’ strongholds. “Hopefully, that will encourage them to talk to each other and break down what I think is a natural barrier in medical schools between the professors and the medical students,” he says. “We can’t force them to talk to each other, but we’ve done everything we can to facilitate that.”