USC Stem Cell Lab Plays the Pragmatic Scientist to Its Site and Context by Zach Mortice

Summary: ZGF’s Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research brings together starkly differing materials to work within the constraints of an inconvenient site. This interdisciplinary lab is designed to maximize modular flexibility and spatial efficiency.

This five-story, 87,537-square-foot interdisciplinary lab is part of a $271 million effort to build 12 new stem cell research facilities in California. After a $30 million gift to the university, it will bear the name of donor Eli Broad, the same philanthropist and civic patron who helped to fund AIA Gold Medal Winner Renzo Piano’s new contemporary art addition to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“You normally want a slightly bigger building, because it creates a community of researchers and it allows you to share expensive equipment,” he says.

Site shielding

|

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Tahoe Science Lab Goes for Platinum LEED

› Harley Ellis Devereaux, HERA Design Nation’s Largest Crime Lab

› Fuel Cell Flux

› The Children’s Hospital Opens New Facility in Aurora, Colo.

› Renzo Piano’s Broad Contemporary Art Museum Opens in LA

Visit ZGF’s Web site.

Graphics courtesy of the architect.

See what the Academy of Architecture for Health Knowledge Community is up to.

Do You Know SOLOSO?

The AIA’s resource knowledge base can connect you to a research paper by Jason Kliwinski, AIA, that compares a number of varying project types—including 19 laboratories—done conventionally and with LEED®. It shows, clearly, that it does not necessarily cost more to build green.

See what else SOLOSO has to offer for your practice.

From the AIA Bookstore: Fourth Factor: Architecture and Medicine by the AIA Academy of Architecture for Health (The American Institute of Architects, 2007)

Captions

1 To preserve open quad space and room for a future building, the Broad Lab’s widest façades face east and west. Courtesy of the architect.

2 The lab consists of four rectilinear masses, all defined by their materiality and level of aesthetic weight. Courtesy of the architect.

3 A multi-level glass skywalk connects the north side of the Broad Lab to the adjacent Zilkha Neurogenetics Institute. Courtesy of the architect.

4 A decorative graphic pattern on the skywalk helps define the lab’s arrival experience. Courtesy of the architect.

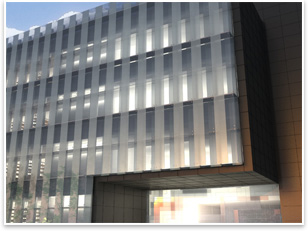

5 The largest mass is a double-paned and finned glass-clad laboratory block. Courtesy of the architect.

6 Visitors and researchers will enter the lab from the east side, into a cut away cantilever. Courtesy of the architect.

7 A double-height atrium offers views up to the second floor and into a fritted, glass-walled conference room. Courtesy of the architect.

8 Spaces about the lab allow for interaction among the researchers. Courtesy of the architect.

How do you . . .

How do you . . .