| Two Restorations Find Another Place for Wright’s Vision in Today One firm takes on a half century of Frank Lloyd Wright architecture Summary: The Davenport House restoration and Glore House renovation by Harding Partners are projects that illustrate the evolving architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. The Glore House received a new addition, and the Davenport House benefited from a LEED®-centered retrofit. How do you ... restore and renovate houses by Frank Lloyd Wright?

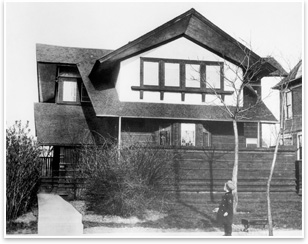

Both houses are located in the northern suburbs of Chicago near Lake Michigan. Harding purchased Wright’s 2,000-square-foot Davenport House in 2004, and he hopes to move into it late this summer. Built in 1901, the Davenport House was Chicago’s first Prairie style Arts and Crafts-influenced house by Wright. It was designed during an early phase of Wright’s career when he was beginning to break away from the European-influenced Beaux Arts models that were used near universally in major cities to create all kinds of civic landmark architecture. Harding detects subtle Japanese influences in the Davenport House’s looming cantilevered pitched roof, but other than that, “he despised historicism,” he says.

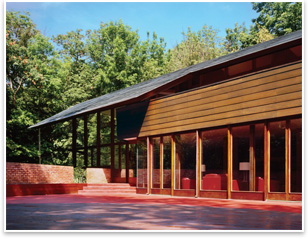

The house sat on the for-sale market for three years before Harding Partners’ renovations began, and clouds of developer knock-down fears had begun to form. To make the house more marketable, Harding designed a family room (which the house lacked) that would fit in under the house’s signature cantilever. The new room extended Wright’s original floor plan and used the Glore House’s material language to create an open and light-soaked room that looks out to the adjacent terrace and ravine beyond. If future owners only want a house touched by the design hand of Wright, Harding’s addition is designed to be completely reversible. The addition won a Merit Award from the AIA Northeast Illinois component. “What we do is take the fabric of the house and work with it so that we use that architectural language and make what we do appear seamless with the original house,” says Harding. Harding Partners and their engineers, Thornton Tomasetti, had access to the Glore House’s original construction drawings. William Bast, a principal at Thornton Tomasetti’s Chicago office, says this allowed them to lessen the impact of the renovations. “We were able to use small invasive holes to do probe openings to check out the structure, as opposed to having to do much more invasive work,” he says.

Harding suspects that the Davenport House (one of five houses that Wright designed during a brief partnership with Webster Tomlinson) might be an important demarcation line that shows the emergence of a repeated motif in Wright’s work. As his career progressed and he moved further from his early Prairie-style explorations, Wright began obscuring the front entrance of his houses. He did this to force his clients to be self-conscious and aware of the simple act of entering their home, so as to demand recognition of the processional ritual from outdoor public space to indoor private space. Two early drawings of the Davenport House show a more traditional front entrance, but a third drawing that is consistent with the house keeps the entrance hidden.

“As much as anything,” says Harding, “it feels like an office project with a really great client, because I get to do it the way that it should be done.” But who is Harding referring to? Who is this “great client”? When he moves into the house he helped design, he’ll still be in a place in which the aesthetic sensibility was created by another and is graciously served by his restorations. “We want to make whatever we do have maximum fidelity with the way it was originally built and designed by Frank Lloyd Wright,” he says. That makes it sound like Wright is the real client here, and Harding is an architect who just sold him on a comprehensive greening for the carbon-insecure 21st century. That’s a deal that will only help to keep Wright’s legacy relevant—and timeless. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Buffalo Spreads its Restoration Wings

› Lake Flato Raises Pearl Brewery’s Spirits

› First Green Building on Capital Hill a Metaphor for Environmental Values

› Washington University Renovations Finds Sustainability by Embracing Its Past

See what the Historic Resources Committee Knowledge Community is up to.

Visit the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Web site.

Photos of the Glore House © Craig Dugan @ Hedrick-Blessing.

Photos of the Davenport House © Paul A. Harding.

(Black and white photos here and in the photo gallery courtesy of the Wasmouth Portfolio.)

At work for more than three years, Gaines Hall, FAIA, is nearing completion of restoring the B. Harley Bradley House in Kankakee, another of Wright's early Prairie School designs. The city and the Community Foundation of the Kankakee River Valley are considering taking over the property and making it a public site. To do that, they will likely be seeking funds to recoup the $2 million investment that saved the home and adjacent stables from decay and collapse. To enjoy the fruits of this Wright restoration, visit the home's Web site.

Glore House

Glore House Davenport House

Davenport House Wright’s houses have long been cited as buildings that lie lightly on the land and are respectful and responsive to their site, and this progressive stance has been easy to translate into current ideas about sustainability. One hundred years ago, Wright maximized the Davenport House for daylighting, pushing it as far north on its lot as possible and providing plenty of windows. The materials used, like the original lime stucco and paint, are eco-friendly, and the new renovations have installed a ground-source heating system (common in many Wright houses) and recycled cypress wood. If everything goes according to plan, the house will be the first LEED-certified Frank Lloyd Wright House ever. LEED Silver is Harding’s goal.

Wright’s houses have long been cited as buildings that lie lightly on the land and are respectful and responsive to their site, and this progressive stance has been easy to translate into current ideas about sustainability. One hundred years ago, Wright maximized the Davenport House for daylighting, pushing it as far north on its lot as possible and providing plenty of windows. The materials used, like the original lime stucco and paint, are eco-friendly, and the new renovations have installed a ground-source heating system (common in many Wright houses) and recycled cypress wood. If everything goes according to plan, the house will be the first LEED-certified Frank Lloyd Wright House ever. LEED Silver is Harding’s goal.

Client W

Client W