The Story of a Country House

Part 6: Fallingwater

by Jim Atkins, FAIA

Summary: In this, the last installment in this series on the best-known American country house, Jim Atkins, FAIA, and his wife, Dr. Sook Kim, travel to Bear Run in western Pennsylvania to experience the magnificently maintained and recently restored country retreat designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, now open to the public thanks to the diligence of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

“Fallingwater is a great blessing, one of the great blessings to be experienced here on earth. I think nothing ever equaled the coordination, sympathetic expression of the great principle of repose where forest and stream and rock and all the elements of structure are combined …”

—Frank Lloyd Wright

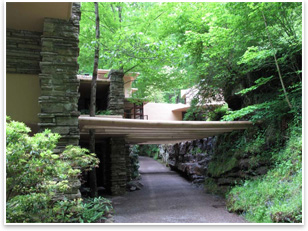

Entering Fallingwater, May 2009. Photo by Dr. Sook Kim, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

This is the final installment of the story of the country house, Fallingwater. In our previous adventures, we followed the Kaufmann family and their discovery and love of the magnificent property Bear Run. We experienced the dynamic and often volatile synergy between Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr. and Frank Lloyd Wright as they made their respective contributions to the creation of the most celebrated house in American history.

We struggled with Kaufmann and Wright through the sometimes turbulent and challenging design and construction phases, and we celebrated the ultimate completion of the masterpiece. However, the continuing deflection and cracking of the reinforced concrete cantilevers threatened Fallingwater’s very existence, and we followed the remediation efforts and the ultimate brilliant correction.

Fallingwater remains the residential treasure of our time, and it awaits and welcomes those who wish to see and enjoy its magnificence. Join us as we visit Fallngwater. It is the most complete work of Frank Lloyd Wright accessible for viewing. Fallingwater is available to the public today because of the excellent maintenance, preservation, and operation by the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, and it awaits your experience and enjoyment. It is the high point in this adventure in architecture.

Western Pennsylvania Conservancy

WPC is a nonprofit organization founded in 1932 that exists to protect the water, land, and life of western Pennsylvania. Since its creation, WPC has protected 225,000 acres (910 km), most of which is publicly owned, and makes up a portion of Pennsylvania’s premier parks, forests, gamelands, and natural areas. For more information and to give your support to WPC, go to www.paconserve.org or call toll-free 1-866-564-6972.

Making a Pitt stop

My wife and I made our pilgrimage to Fallingwater in late May 2009. We arrived at the Pittsburgh airport just after noon and made a quick run through the tunnel and over the river to downtown Pittsburgh before our drive down to Bear Run. The city sparkled, a gleaming ascendant of the more crusty days of the steel mills and foundries that I had seen many years before. On this day, a vibrant city stands where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers come together to form the Ohio River. It is as if the old steel mill town environment was a cocoon from which this transcendent city has emerged. It is easy to see why Pittsburgh in recent years has been ranked among the most desirable cities by livability surveys.

Kauffman’s “Big Store,” today. Photo by Jim Atkins, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

We went straight away to the big store and Kaufmann’s clock at Smithfield and 5th Avenue, and we were not disappointed. Downtown was very much alive as if E. J. had never left. The red awnings of Macy’s now adorn the old building, but many of the Kaufmann signs are still visible outside.

The drive to Mill Run

After our visit to the big store, we headed south toward Mill Run. Quite by happenstance, we charted a route that essentially retraced the path Kaufmann routinely took in the 1930s. You may wish to do the same. I searched for the directions using one of the available mapping options on the Internet, and I asked for the shortest route. The result was a complex, yet direct journey through the neighborhoods of east Pittsburgh.

We followed the intricate map directions, driving narrow streets that passed through quaint, sleepy intersections with family run shops and markets. The trip took over two hours as it reportedly did for Kaufmann in the 1930s. Except for a stretch on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, we consistently followed the footsteps of the Kaufmanns on their routine travel to Fallingwater. Although the route was time consuming, I was thrilled that we were re-tracing Kaufmann’s steps through this otherwise inconvenient excursion.

Allegheny County

The drive along the Laurel Highlands Scenic Byway from Pittsburgh to Mill Run is a feast for the senses. The southwestern Pennsylvania countryside is natural beauty to behold, and it should not be missed any time of year. On this trip the countryside is a vibrant green from the intermittent spring rains, and it is easy to understand why Kaufmann loved the Allegheny Mountains as he did.

It appears that not much has changed in the highlands over the past 70-plus years. On leaving the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the speed limit is typically 35 mph as the road works its way through the small, sleepy country towns. I found myself relaxing and “gearing down” as I was forced to move at this slower pace. I imagined Kaufmann experiencing the same transition as he traveled to his favorite getaway.

Fallingwater remains significantly remote and the countryside unspoiled. To date, there has been no commercial development capable of altering the calm atmosphere of Stuart Township. Obviously that was an important part of its attraction to Kaufmann 70 years prior. There is no hotel within 30 miles of Fallingwater, but the small and lovely Country Seasons Bed and Breakfast in Mill Run accommodated us quite nicely.

Since Mill Run is generally unchanged from Kaufmann’s time, if you disregard the modern automobiles and a few contemporary signs, the humble surroundings can easily take you back to the 1930s. When we stopped at the local grocery store for snacks, I noticed a large, dark sedan coming south down Route 381, and I couldn’t help but fantasize that it was Kaufmann and his driver headed to Fallingwater for the weekend.

The clean fresh air was exhilarating, and the quiet of the countryside calmly refreshing. It was a much needed pause in my busy schedule and a welcome departure from large cities and busy airports; a most fitting preamble to our visit to Fallingwater the next day.

Fallingwater

Edgar J. Kaufmann jr’s gift of Fallingwater to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy is a priceless treasure, and the conservancy lovingly and meticulously cares for it and provides for a most beneficial public experience. Director Lynda Waggoner and her capable staff are waiting for you to come visit this unique national treasure.

The entrance to Fallingwater is approximately three miles south of Mill Run on Road 381 to Ohiopyle. We turned in at the entrance and drove a short distance to the gatehouse, which happens to be near the abandoned location of the Kaufmann’s old Hangover cabin. A short distance beyond the gatehouse we encountered the parking area and the Visitors Center.

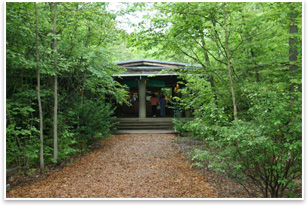

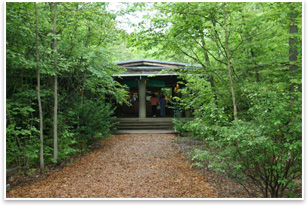

The Visitor’s Center nestled in the forest above Fallingwater. Photo by Jim Atkins, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

The Visitors Center is nestled in the forest above Fallingwater, and its open air design includes a reception area, a museum store and a restaurant to provide for most visitors’ needs. Tours leave from the Visitors Center, and advance reservations are recommended, especially in the peak months of July, August and October; for more information go to www.fallingwater.org.

We chose to begin our visit on a Wednesday, a non-tour day when only the grounds around Fallingwater are available for viewing. We were able to move freely around all of the structures and photograph at will for our own personal use. This allowed us greater opportunities for photo shots with few or no people.

The next morning we took the guided tour. This is an opportunity that should not be missed. The guided groups are small, and the guide’s commentary greatly enhances the experience. Our tour began at the Visitors Center and continued down the wooden walkway to the entrance road the Kaufmanns originally drove to get to Fallingwater. From there we walked along the enchanting tree shaded road to the summer house. Soon we began to hear the melodic sound of the waters of Bear Run, and through the filtered greenery we began to gradually make out the ochre tones of the house in the forest before us. Our hearts raced as we realized that we were about to encounter Fallingwater. I imagined that I was E.J. on my way from Pittsburgh to relax for the weekend, and I had finally arrived at my country treasure. The feeling was pure magic.

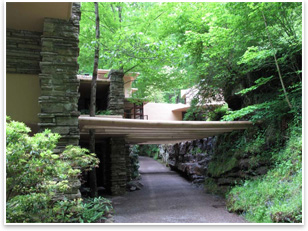

The understated entrance to Fallingwater, behind the tree on the left. Photo by Dr. Sook Kim, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

As we came upon the house, it was a greater pleasure than we could have envisioned. It is without question Wright’s most successful marriage of architecture and nature. As we crossed the entry bridge we could see Bear Run flowing vibrantly below us. The cool, clear waters embraced the architecture above it to make our experience overwhelming.

The experience of the building has often been likened to a choreographed dance. Wright clearly controls how you are going to experience the building. I think the entryway is a great example of that.

—Lynda Waggoner

The entrance

The entrance to Fallingwater is not a dominant feature of the house. In fact, you cannot see it until you have crossed the bridge. As you approach the house, on your left the entrance door is only discernable through a narrow slit between two rectangular stone columns. My first impression was that of a servant’s passage.

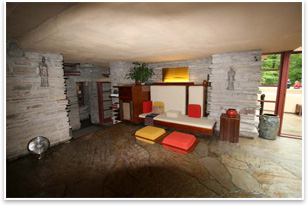

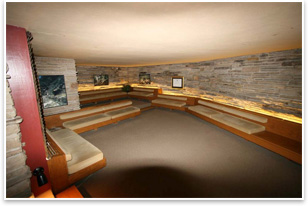

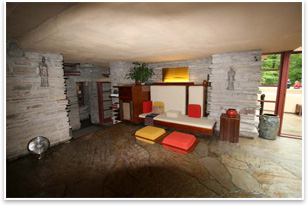

“Compressed” entrance to the Great Room. Photo by Jim Atkins, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Upon entering the house, one walks up a half level of stairs to the much larger great room. This feature of entering from a small space to a larger area was frequently used by Wright to dramatize the destination, which in this case is the largest space in the house. It has been called a “compression entrance” because it forces the visitor to negotiate a small, unassuming entry and be faced with a large, dramatic space that makes a major statement in the design as well as the viewer’s experience. My psychologist wife informs me that the drama it creates is a fitting projection of Wright’s flamboyant and dramatic personality.

Lilliane’s bedroom, note the thickened beam at the ceiling to support the upper terrace. Photo by Jim Atkins, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

The interior

The interior spaces of Fallingwater most appropriately define its purpose and existence. I could feel the personalities of E.J., Lilliane, and Edgar jr. as we viewed their personal quarters. EJ’s and Lilliane’s bedrooms are on the same level just above the great room, and EJ jr’s quarters are on a third level just above E.J. Sr. A modest guest bedroom is on the same level as the great room, but it became secondary quarters after the guest house was finished.

EJ’s Bedroom, simple and more masculine than Lilliane’s. Photo by Jim Atkins, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

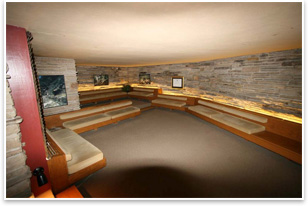

It is as if the spaces could only be theirs; the feminine texture of Liliane’s bedroom, the masculine feel of E.J’s., and the studious and scholarly accommodations for Edgar, jr. with its many bookshelves and his bedside reading stand. Wright has created the perfect accommodation for the Kaufmann family, and he has created it in their favorite environment as a part of the flowing stream. It is absolutely breathtaking.

EJ jr’s Study, located above EJ’s bedroom. Photo by Jim Atkins, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

The great room is warm and welcoming, and I could imagine the family together, warming hot cider in the large pot on the fire and experiencing the snow covered exterior in winter. But today I can feel and smell the earthy greenness of spring and the closeness of the house with its powerful environment, rhododendrons soon to be in bloom. It is a place for enjoyment any time of year.

The great room with the protruding stone hearth. Photo by Jim Atkins, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

The modest dining area is in the southwest corner of the great room. Although Wright designed dining chairs for the Kaufmanns, Lilliane declined his creation in favor of a three-legged chair that she had found in Europe.

Meals were served from the kitchen adjacent to the dining area. It was equipped with metal cabinetry and the most modern appliances available at the time. However, as appliances improved, it was upgraded by the Kaufmanns to include perhaps the first KitchenAid dishwasher and one of the first side-by-side refrigerators.

Dining area with kitchen entrance door in the corner. Photo by Dr. Sook Kim, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Fallingwater is more than a building, more than a house, and more than a place in the country. It is an experience that everyone must see, and breathe, and feel, at least one time in his or her life. It is what architecture is meant to be, and it is a magnificent treasure for everyone to experience and enjoy.

Too often we are rearranging nature to suit us, Wright doesn’t do that. He allows nature to speak for what it is, and allows us to access it in ways that we are unaccustomed to…

—Lynda Waggoner

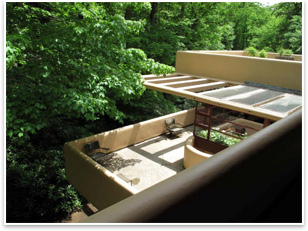

EJ’s Terrace, the stairs lead up to EJ jr’s study. Photo by Jim Atkins, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

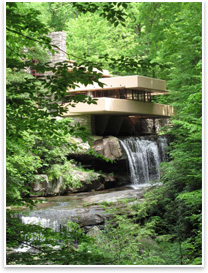

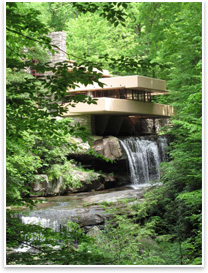

The money shot

The most famous view of Fallingwater is available as you leave the house and cross over the bridge at the entrance. Leaving the house, take the path to your right back to the Visitors Center and watch for the sign. The path from the sign will lead you back down to the stream. Remember that Fallingwater is most often seen looking up from below. It is the view that Edgar Kaufmann Sr. initially envisioned as the location of the country house.

We follow the winding path downward, and it leads to a small viewing area by the stream where there was a park bench for resting. From this vantage point we could see the classic view of Fallingwater. On the day of our visit there were only two other couples and was plenty of time to frame our shots.

“The Money Shot,” May 2009. Photo by Dr. Sook Kim, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Small, isolated rain cells had drifted through the area all week, and we were blessed with cool temperatures, filtered light for our camera shots, and most of all just the right amount of water coming over the falls to frame the house in an idyllic setting.

The Guest House

After our guided tour of the country house, we ascended the stair-stepped covered walkway to explore the Guest House, completed two years after Fallingwater in 1939. It consists of three bedrooms for the service staff and a spacious guest sitting area and bedroom. A three-car carport is attached, now converted into a video room used to showcase the conservancy as the tour’s concluding feature. The three servant’s bedrooms are currently used as offices by conservancy staff.

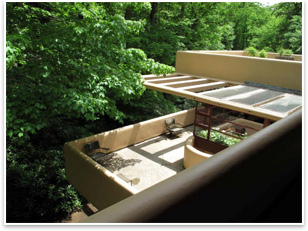

The Guest House above Fallingwater. Photo by Jim Atkins, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

That is where we met with Clinton Piper, the archivist for Fallingwater. He provided us with the historical images that we used in this series. As we conversed about the house, I couldn’t help but imagine how the room may have felt to the servant that resided there during the time of Edgar and Lilliane. The house was famous from its very beginning, and the wait staff must have felt its magic in their daily duties.

Guest House sitting area. The stepped canopy outside leads to Fallingwater, below.” Photo by Jim Atkins, Courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

The stonework at the guest house is the finest of all masonry work at the facility, confirming the priceless value of the learning curve. A spacious swimming pool adjoins the guest house on the east side, perpetually fed by the cool waters of Bear Run.

Today, in the converted carport where we were given a brief introduction to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, the air conditioning is refreshing after the two-and-a-half-hour tour, and I can find no better way to end a Frank Lloyd Wright house tour than by resting on seating that he designed. I expected E.J. to come walking into the room to offer us all a drink and ask if we want to take a dip with him in the falls.

The converted carport. Photo by Jim Atkins, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

A refreshing experience

At the end of the tour, I sat briefly by the pool and imagined how enjoyable it must have been to be one of the many invited guests of E.J. and Lilliane, splashing in the pool and the waterfall and enjoying the tranquil atmosphere of Wright’s creation in the calmness of the Allegany forest.

I thought how magical it must have been to share the house and have a drink on the terrace by the great room, or enjoying private time in the guest house; servants scurrying about, bringing a snack or turning the bed.

But most of all I thought about how special it must have been to have had Fallingwater as my own place of being; feeling, hearing, and smelling Bear Run below, and embracing the intimacy with nature in a way that only Wright could provide; standing on the terrace at night, listening to the sounds of the forest, or awakening to the piercing sunlight as it breaks through the bedroom windows at morning. I can’t possibly imagine a more serene and enjoyable experience.

Great Room terrace as seen from Lilliane’s terrace. Photo by Dr. Sook Kim, courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Reflections

This concludes our visit to the country house, Fallingwater. This Frank Lloyd Wright creation is much more magnificent and enjoyable than any promotional literature or this article series can possibly convey. No picture can adequately provide the complete magic of the place itself. One can experience it to its fullest only in real time. Every architect and for that matter everyone interested in great architecture should see it, be inside it, and personally take in its wonderful atmosphere at least once.

Yet this magnificent masterpiece was not created by luck or chance, it did not achieve reality with any ease of deliberation. It came about almost by accident. It was the child of two arrogant, driven men who had a score to settle; two extremely talented individuals, who, by the sweat of their own dogged determination and will, made it what it is.

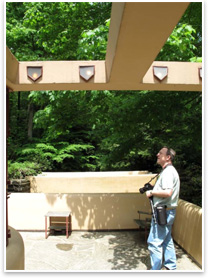

Great Room terrace as seen from EJ’s Terrace. Photo by Dr. Sook Kim, Courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Many of us who have been in the industry for awhile can relate to the struggles and challenges encountered by Kaufmann and Wright. Many of us have likely had projects that did not come about with ease and accommodation. The real appreciation is that their struggle occurred during a time when communications were much slower, building material selection more limited, and technology much less developed. I stand in awe of the extensive and magnificent cast-in-place concrete in Fallingwater, knowing that it was put there with a hand-operated cement mixer, a wheelbarrow, and a shovel, delivered one scoop at a time by the human hand.

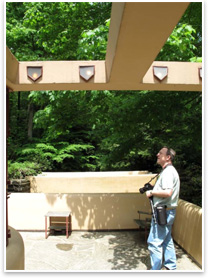

The author photographing from the Great Room Terrace”, Photo by Dr. Sook Kim, Courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

The objective of this series has been to explore the realities of this country house, including its limitations, challenges, hardships, and adversities. Such awareness can give the admirer a greater gift than a mere appreciation of its aesthetic detail and design. It can enrich with the awareness that greatness does not always happen casually or with ease, and it can hopefully convey a better understanding of the immense price required by those who created it, in such a complex struggle of personalities, during the Great Depression, in this little glen on Bear Run Creek.

I sincerely hope that this article series has brought you a little bit closer to the magic of the country house known as Fallingwater, and I encourage you to visit the house personally and experience its magic. And until next time, good luck out there. |