The Story of a Country House

Part 2: Bear Run, Kaufmann, and Wright

by Jim Atkins, FAIA

I conceived a love of you quite beyond the ordinary relationship of client and Architect. That love gave you Fallingwater. You will never have anything more in your life like it.

—Frank Lloyd Wright to Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr.

The entrance to Fallingwater.

Photo by the author and courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

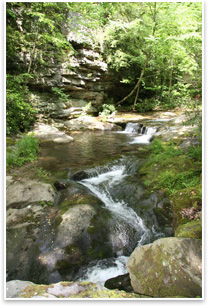

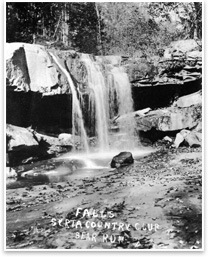

Bear Run is a creek in eastern Fayette County, Pa., in the Allegheny Mountains and a part of the southeastern Pittsburgh metro area. It flows from Laurel Hill, dropping almost 1,500 feet to the Youghiogheny River. In places it flows through the brown and grey horizontal strata of weathered sandstone and, at a certain location, falls more than 20 feet from an outcropping of cantilevered rock in a dramatic waterfall.

It was this natural feature that attracted people to the area; first the Masons in the late 1800s who built a “Masonic Country Club” for recreation. The enterprise eventually failed, however, and it was sold at sheriff’s auction. Similar subsequent enterprises failed as well, and the site was sold two more times at auction until another Mason group, the Syria Improvement Association, bought it in 1909. They erected a large wooden structure almost a quarter mile south of the falls, the Syria Country Club, along with numerous outbuildings.

Syria leased the encampment in 1916 to the Kaufmann Beneficial and Protective Association, an employee group within Kaufmann’s department store, and it was called Kaufmann’s Summer Club, a recreational vacation club for women employees. The camp was easily accessible by rail, a two hour train ride from Pittsburgh.

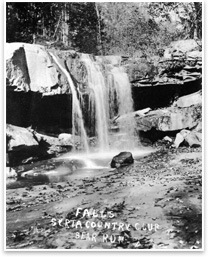

Kaufmann’s cabin, “Hangover.”

Photo courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

The property changed hands again in 1918, and in 1920 Edgar Kaufmann was invited to purchase 300 acres and all improvements for $25,000. He declined. The association leased the property again in 1921 for a five-year term. That same year, Edgar purchased a mail-order cottage from the Aladdin Company of Bay City, Mich., and had it erected on the property near a cliff just west of the road from Mill Run to Ohiopyle, approximately one quarter mile south of the waterfall. The cottage, known as “Hangover” by employees and locals, had no heating, plumbing, or electricity. Nonetheless it became the Kaufmann’s haven of escape from their bustling life in Pittsburgh.

The Aladdin Company, founded in 1906, was a pioneer in the pre-cut mail-order home industry, and their competitors were Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck and Company. By 1918 sales were over a million dollars annually, and their products accounted for over 2.3 percent of all housing starts in the United States, or about 1,800 homes. Sales suffered during the Great Depression, and the company sold only a few hundred homes per year during the sixties and seventies. By 1982, the company ceased manufacturing, and it closed its doors in 1987.

Ultimately, in 1926, the association purchased the entire property, which at that time was almost 1,600 acres. But the ensuing Great Depression made the $15 annual dues difficult to come by, and employee interest in the camp began to wane. With little use, the buildings fell into disrepair. Even so, Kaufmann cherished the land and kept it up by cleaning out deadwood, planting new trees, and restocking trout in the stream.

The waterfalls before Fallingwater.

Photo courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Kaufmann and his wife eventually took personal ownership of the property in June, 1933. The land was a favorite getaway for the Kaufmanns, and by this time they had become committed conservationists. In 1934, with their mail-order cottage beginning to show its age, they decided that they should find a suitable architect to design them a special house near the falls.

The Kaufmann-Wright alliance

Most accounts of the Kaufmann-Wright relationship support that it was Edgar jr. who first discovered Frank Lloyd Wright and matched him up with his father. However, as observed in part one, the author and historian Franklin Toker maintains otherwise. Toker is of the opinion that Kaufmann and Wright were already in contact before Edgar jr. discovered the architect in 1934. He bases his belief on correspondence that he discovered during his research that predates the experiences of Edgar jr.

He found that Edgar Sr. had contacted Wright by letter in August 1934 regarding participation in the development of civic projects in Pittsburgh. Wright later responded that he could not afford to travel to Pittsburgh at that time due to his slow work activity.

In late September, Edgar jr. traveled to Taliesin to interview as a candidate for a fellowship in Wright’s Taliesin School. By this time, Wright had sized up Edgar Sr. as a viable potential customer who could fund the design and construction of a significant project, even during a depression.

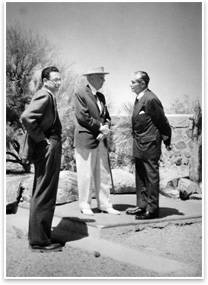

Edgar jr. joined the Taliesin fellowship in mid-October of that year. He writes in his book, Fallingwater: A Frank Lloyd Wright Country House, that it was never his intention to become an architect, but only his appreciation for Wright and his philosophy and designs that lured him there. Nonetheless, by mid-November the elder Kaufmann and his wife arrived at Taliesin for a visit. Edgar and Frank hit it off from the start, and their relationship would last throughout the remainder of their lives.

As they became acquainted at Taliesin, they initially talked about Pittsburgh and building a planetarium there. They also compared notes on Wright’s Broadacre City, his plan for development of an American prototype community. As the evening drew on, Wright persuaded Kaufmann to back him financially in presenting Broadacre City at a New York exhibition. Edgar agreed. This would give Wright an opportunity to travel through Pittsburgh in mid-December when he would again meet with Kaufmann.

Broadacre City: A suburban development concept proposed by Frank Lloyd Wright late in his life, it was first presented in his article, The Disappearing City, in 1932. It supported the newly born suburbia brought about by the automobile, yet shaped through Wright's particular vision. Each family would receive a one acre (4,000 sq. meter) plot of land taken from the federal land reserves. Wright developed his community based on a grouping of these parcels. However, unlike transit-based developments, Wright’s concept was based on transportation by automobile, and pedestrian circulation was relegated essentially to the one-acre plots.

Meet me in Pittsburgh

Wright met with Kaufmann in Pittsburgh on December 18, 1934. They first discussed Edgar’s new office that he wanted to build on the 12th floor of the department store.

Afterwards, they went down to visit Bear Run. Kaufmann showed Wright the waterfall and the property. He explained the vision he and his wife had for their country house. They wanted a more livable place, closer to the waterfall than the Hangover cabin, and they wanted it equipped with modern utilities so that they could use it year-round.

Wright walked the property, examining the lay of the land. He studied the falls and the land around it. He requested that Edgar send him a topographic survey that would locate and identify the features of the property; the rocks, the stream, and all trees with a caliper of six inches or larger. The survey would have elevation contours that could indicate the fall of the land so that the house could be located and planned.

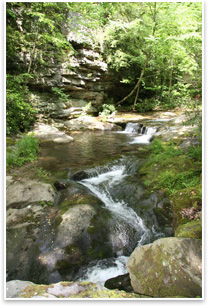

Bear Run upstream from Fallingwater.

Photo by the author and courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

The survey was not completed and sent to Wright until early March of 1935, possibly because of the Kaufmann’s travels out of the country.

The music of the stream

The coming together of Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr. and Frank Lloyd Wright in 1934 was improbable to say the least. Years before, Kaufmann had commissioned Benno Janssen to design La Tourelle, his house in the fashionable Fox Chapel area of Pittsburgh, and the Norman-style mansion was a significant departure from the Modern inclinations of Wright.

Wright, on the other hand, at 67 years old, was looked upon by many as an elderly architect who was no longer in the mainstream of leading-edge design. His work was not displayed at the 1932 New York Museum of Modern Art exhibition on Modern architecture, which included work by Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier. Wright’s perceived absence from mainstream Modernism and the two men’s previously divergent preferences in architecture makes the strong alliance that developed between them appear quite extraordinary.

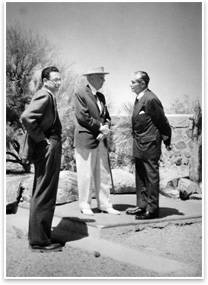

Kaufmann and Wright at Taliesin.

Photo courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Franklin Toker, in Fallingwater Rising, posits that the two men were driven by similar devices. He maintains that they were in “lockstep.” Kaufman was motivated by his desire to exercise revenge over the elitist snobs of Pittsburgh, who would not allow him social parity, and Wright was out to show the European architects that he could take their breath away and prove they held no monopoly on Modernist architecture.

It was this lethal mixture of the two men’s intelligence, strength, and determination that was required to make Fallingwater happen. And considering the ensuing obstacles and challenges in its path, such a mixture was good fortune indeed.

Yet Edgar and Frank did find each other, and the project was built. Kaufmann no doubt had resolved in his mind early on that Wright was the man for the job, and Wright, upon visiting Bear Run the first time, was obviously quite enamored with the opportunity; especially the palette on which to do the work. After Wright’s first visit, he would later write: “The visit to the waterfall in the woods stays with me, and a domicile has taken vague shape in my mind to the music of the stream.”

The wonderful property, the setting of Bear Run, and the respectful relationship between Kaufmann and Wright provide the ingredients architects look for in a successful project. With the stage now set for Wright to begin in earnest on Fallingwater, there was nothing to hinder meaningful progress on the design of this architectural masterpiece. Or was there?

Next installment

Experienced architects are well acquainted with the problems that can plague a project: delays, poor communications, and conflicting information. Fallingwater proved no exception to any of these. The next installment will explore the exciting, sometimes fast moving and sometimes glacial path of the design process. Until then, good luck out there. |