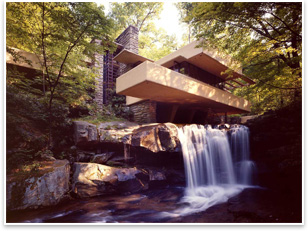

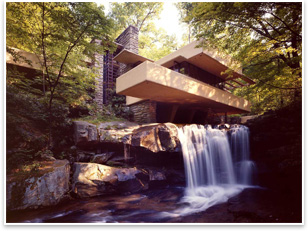

Fallingwater

The Story of a Country House

by Jim Atkins, FAIA

. . . all the elements of structure are combined so quietly that really you listen not to any noise whatsoever although the music of the stream is there. But you listen to Fallingwater the way you listen to the quiet of the country.

—Frank Lloyd Wright, 1955

Fallingwater by CORSINI. Photo courtesy of Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Times were tough in 1934. The Great Depression was taking its toll on America, and people were struggling; including the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Now, at 67 years old, none of his designs had been constructed since Darwin Martin’s summer home, Graycliff, in 1929. His income came primarily from the Taliesin Fellowship, his school for apprentice architects at his home in Spring Green, Wis.

Few people had money in that time, but Edgar J. Kaufmann was an exception. He was the president of Kaufmann’s Department Store in Pittsburgh, a family enterprise begun in 1871 that became the merchandizing behemoth of the eastern United States. The store was a landmark—12 stories built on the corner of Fifth Avenue and Smithfield Street—and the business was essentially recession-proof. It was a staple of the local economy.

The Kaufmanns had a getaway camp on Bear Run creek in Stewart Township just 50 miles southeast of Pittsburgh, but the wooden structures there were in sad repair. It was an old Masonic camp they purchased and used for recreation for their employees. Now, Edgar was contemplating the construction of a country house on the site. Bear Run Creek had a striking feature; a waterfall cascading from a rock outcropping that was beautiful to observe and fun to enjoy. It had become the Kaufmann family playground.

They commissioned Wright to design the country house near the falls. The end result has become an American icon. It is without question the most celebrated private residence in America. Join us for the next six months as we experience the story of Fallingwater; its conception, its construction, and its legacy.

It is a story set in times much like those we are experiencing today—a recessive economy, a time of repressed construction and design—and the project was wrought with continuing construction problems as it rose from its foundation in the clear, cool waters of the sandstone creek bed.

It was from the unique personal relationship of Wright and Kaufmann and these defying adverse challenges that a most profound and celebrated contribution was made to architecture and design. It is the story of the country house, Fallingwater, a true adventure in architecture.

Part 1: The Kaufmanns

The origin of the Kaufmann name is German and Jewish, and it is an occupational name for a trader or shopkeeper. The base form kouf (from Latin caupo ‘merchant’) was augmented by suffixes, -er, -el, -man. Thus it is no surprise that the Kaufmann family, German immigrants, came to the United States to set up shop.

In 1869, Issac Kaufmann came to the United States to join his brother Jacob, who had immigrated to Pennsylvania from Hesse-Darmstadt. The brothers worked the settlements along the Youghiogheny River, peddling clothes to the villagers, farmers, and coalminers. Working the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, their work took them through the scenic area of Bear Run.

They opened a clothing store on Pittsburgh’s south side in 1871, and, with business thriving, in 1872 they moved into a larger building. Their brothers Morris and Henry came over from Germany and joined the business, and together they added yet another store on the north side of town. With much hard work and a successful trade, by 1878 they closed the two stores and opened a much larger store downtown on Fifth Avenue and Smithfield Street, known since as “the big store.” Business continues there today under the Macy’s brand.

Morris Kaufmann and his wife Betty had four children, Stella, Edgar, Martha, and Oliver. Status within German Jewish families was regulated to some extent by Judaic law, with the eldest boy and girl being given status over their younger siblings. The elder son was expected to go into the family business, and it was common for brothers to be business partners. Edgar Jonas Kaufmann was the second child and the eldest son.

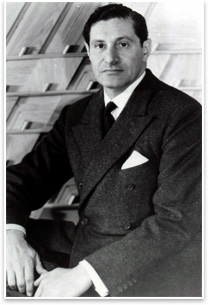

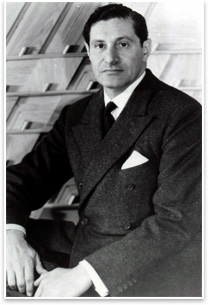

Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr. in Wright’s office. Photo Courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr.

There was likely a great expectation that Edgar Jonas Kaufmann, or E. J. would enter the family business, and he was no exception to this aspect of his family heritage. He received his secondary education at Shady Side Academy in Pittsburgh, followed by a stint at the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University.

He then began an apprenticeship in retailing at the finest establishments: Marshall Fields in Chicago, Les Galeries Lafayette in Paris, and Karstadt in Hamburg. His blue blood retailing experience was tempered with a jaunt at the general store in Connellsville, Pa., a meager establishment just up the road from Bear Run. He was well rounded and well prepared to lead the family business.

In 1909, he went to work at the big store downtown and married his first cousin, Liliane. By 1913 he had bought Henry Kaufmann’s share of the store as well as that of his uncle Isaac. His uncle Jacob had died in 1905 and left his shares to his brothers. Edgar, now only 28 years old, was minding the store in a big way.

He made the most of the healthy economy spawned by World War I and increased the store’s sales threefold from 1913 to 1920. Under Edgar’s direction, the store prospered and became the largest department store in Pittsburgh with 12 stories covering an entire city block comprising 750,000 square feet of selling space. Built in 1887, it was remodeled several times before receiving its current look. In 1913, the architecture firm of Benno Janssen and Franklin Abbott designed a section of the building sheathed in terra-cotta with classical renaissance detailing and a large ornamental public clock at the street corner.

In the late 1920s, Edgar commissioned a redesign of the main floor, and local architects Benno Janssen and his partner William Cocken created an art deco masterpiece. The interior columns and much of the walls were clad in black reflective marble and Carrara glass, a new product recently introduced by the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company. With terrazzo flooring, ornamental bronze metalwork, and an elevator retrofit, the improvements were worth over a million dollars.

PPG Carrara structural glass

Opaque structural glass slabs were first developed around 1900 as a more hygienic alternative to marble slabs for wainscoting and table surfaces. In 1906 the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company (PPG) began production of Carrara glass in white and black. It reached its greatest popularity in the 1930s with applications responsive to the Art Deco style. By the 1950s it began losing its appeal, and the last time it was displayed in Sweet’s Catalog was 1963.

Kaufmann’s Clock. Photo courtesy of the author’s wife, Dr. Sook K. Kim.

The building became a local landmark in Pittsburgh, and the phrase, “meet me under Kaufmann’s Clock” was commonplace when people would meet up to shop in the store and eat at the Tic Toc Shop inside. Christmas was especially grand where generations of shoppers would go to meet Santa Claus and see the monumental Christmas displays.

Edgar J. Kaufmann, Sr. was a wealthy, successful, self-made entrepreneur in the Pittsburgh dry goods business by the time he married his wife Liliane in June of 1909, and she was an intelligent, stylish strong-willed woman who could hold her own in the retail business.

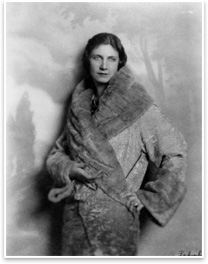

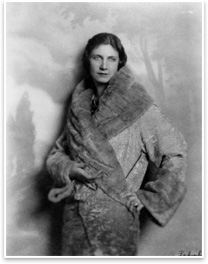

Liliane Kaufmann in wrap. Photo courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy

Liliane Kaufmann

Lillian Sarah Kaufmann was born to Morris’ brother Isaac, which made her and Edgar first cousins. (She changed the spelling of her name to Liliane.) They had known each other all of their lives, and it is likely the marriage was arranged. Intermarriages and arranged marriages were common among German Jews in the late 19th century to accommodate financial, familial, and ethnic/religious considerations.

A hint to the arranged marriage is given by Liliane herself in an interview with a New York Times reporter on their trip to New York City to get married. It was illegal for first cousins to marry in Pennsylvania at the time.

The New York Times interview, dated June 22, 1909 reads:

“Yes, we are first cousins, and we came to New York to get married because of that fact,” Miss Kaufmann said to a Times reporter yesterday. “I have known my cousin all of my life, but we have been engaged only a short time. There is no romance connected with our marriage, except that we came here in a special train, if you consider that one.”

They were married that evening at the St. Regis Hotel. The wedding was somewhat austere, attended by close friends and family. The only attendants were Liliane’s sister, Martha, and Edgar’s best man, Edward M. Meyer. There were no ushers. After the wedding there was a dinner, followed by dancing in the drawing-room suite. The bride and groom left that evening for an auto trip through the White Mountains.

Liliane was very involved in the family business and introduced the people of Pittsburgh to the fashions of Paris. She turned the then-unprofitable 11th floor women’s shop into the successful boutique, Vendôme, a reflection of the elegant Place Vendôme in Paris. She traveled through Europe to keep it stocked with antiques, artwork, and interesting objects d’art.

She ruled the Vendôme completely, returning from her buying trips to Europe with the flair of royalty, her attendants and chauffeur in line behind her. To her secretary at the time, Mary Michaely, it was like the return of a queen to her palace.

She was a significant local leader, especially in the hospital community, tirelessly supporting both Montefiore and Mercy hospitals.

In 1910, after less than one year of the marriage, Edgar J. Kaufmann jr. was born.

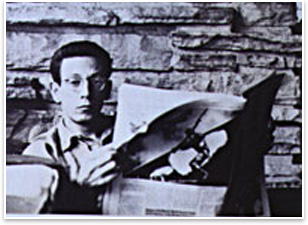

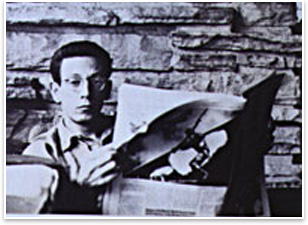

Edgar J. Kaufmann jr. at Fallingwater. Photo courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Edgar jr.

Edgar J. Kaufmann jr. was the only child of Edgar and Liliane Kauffman. He studied in Europe and had a strong interest in art and architecture. He taught architectural art and history at Columbia University from 1963 until 1986, and he was well respected for his knowledge of the arts and his civic benevolence. Among his gifts was the Alvar Aalto Conference Facility at the Institute of International Education in United Nations Plaza in New York City. He commissioned Aalto to design the facility in the 1960s, and it is only one of four Aalto designed projects in the U.S.

Ironically, one of his purported accomplishments, vigorously perpetuated by Edgar jr. himself, was that it was he who initially brought together his parents and Frank Lloyd Wright to create Fallingwater. This has been boldly challenged by Franklin Toker in his book, Fallingwater Rising. Instead, Mr. Toker believes that it was Edgar Sr. who initially contacted Wright after learning of his 1926 design for a planetarium and parking garage in Maryland.

Toker found letters indicating that Edgar Sr. had been corresponding with Wright as early as January 1934, if not before. This and other documentation led him to the position that it was Edgar Sr. and Wright who came up with the idea of young Edgar’s apprenticeship at Taliesin instead of the more popular belief that young Edgar searched and sought it out on his own.

The potential historical variations notwithstanding, the greatest accomplishment of Edgar J. Kaufmann jr. is undisputed, for it was he who forever preserved Fallingwater for the public’s adoration and enjoyment by giving it and the surrounding area to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy in 1963. Incidentally, the lower case jr. is not a typo. It is Edgar jr’s. preferred spelling.

The marriage

The Kaufmanns lived high in Pittsburgh society, but not at the very top. Although they lived in La Tourelle, a mansion in the highbrow suburb of Fox Chapel, and they ran with the country club elite, because they were Jewish they were never admitted to the pinnacle, where the Carnegies and the Mellons resided. Despite Edgar’s civic accomplishments and benevolence, he was never allowed membership in the elitist Duquesne Club.

Nonetheless, they made quite a couple, and they made their mark in local circles.

The Duquense Club. Photo by Jim Atkins, FAIA.

The Duquesne Club

Formed in 1873 by Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick as a “place to talk business, smoke cigars and play billiards.” For a fee of $200 and annual dues of $50—a tidy sum of money at the time—a member could dine and relax in a private setting. Membership, gained only by invitation from an existing member, has grown from its handful of founding members to around 2,700 today. In the days of Edgar Kaufmann Sr., the club prohibited membership to women, Jews, Blacks, or other minorities. Today, the club does not discriminate on its selection of members on the basis of race, color, sex, or religion. The first Jewish member was admitted in 1968, the first woman in 1980, and the first African American in 1983.

Edgar was a front line player in local politics, and he fought to improve the city and help it survive the great depression. He supported public projects, although none were realized. He was a generous employer and knew the names of his workers, greeting each of them and asking about their families.

The Kaufmanns were seen by the public as a happy, successful married couple, often taking weekends at Bear Run, enjoying their family life together in the outdoors. They were liberated, and, years later in 1947, Elsie Henderson, a house servant, would speak of her shock and surprise at seeing Edgar and Liliane bathing nude with their friends in the chilled waters of the falls.

The Kaufmann marriage remained intact for many years, but it was likely not because of intimate dedication and unqualified love. Edgar was a known philanderer who allegedly fathered a child with a store employee. He kept so many mistresses, according to the historian Franklin Toker, that he had the store provide special charge cards for them.

Liliane endured his publically visible extramarital behavior, but it apparently took its toll on their relationship. By 1951 Edgar had fallen in love with his nurse, Grace Stoops, and she began seeing him in Palm Springs at their vacation house designed by Richard Neutra.

On September 7, 1952 during a weekend stay at Fallingwater, Liliane was found by the servants on her bed, having overdosed on sleeping pills. Because of his distrust for the local doctors, Edgar drove her for two and one-half hours to Mercy Hospital in Pittsburgh. She was pronounced dead upon arrival. Some have speculated that the delay in traveling to Pittsburgh caused her demise.

Although Edgar jr. maintained that his mother had taken her own life, he may have been wrong. Both Edgar and Liliane drank heavily, and Edgar kept painkillers around because of his chronic back pain, an unhealthy combination. The coroner ruled the death accidental.

Neutra’s Kaufmann Desert House

A five-bedroom, five bathroom vacation house designed by Richard Neutra for Edgar Kaufmann Sr. in 1946 in Palm Springs, Calif., the Kaufmann Desert House is one of the most important examples of International Style architecture in the United States still in private hands. After Kaufmann died in 1955, the house had multiple owners and received many compromising design renovations.

Brent and Beth Harris, she an architectural historian, bought it in 1993 for $1.5 million and meticulously restored it to its original design. After they divorced, it sold in May 2008 for $15 million at auction by Christie’s. However, the sale fell through, and in October 2008 it was listed at $12.95 million. It remains unsold today. Critics have lauded the house as one of the top five of the 20th century and placed it within the ranks of Fallingwater.

Next month

Join us next month as we explore the majesty of Bear Run Creek, the Kaufmann family playground that provided the palette for Wright’s masterpiece. We will examine the strong personalities of Wright and Kaufmann, how their association developed, and how Wright gained the commission on Fallingwater.

It was this volatile mixture of the two men’s intelligence, strength, and determination that made Fallingwater possible, and considering the ensuing obstacles and challenges that lay before them, such a mixture was fortuitous indeed. Don’t miss our next adventure with the country house, Fallingwater, and until then, good luck out there. |