Solar Decathlon Advances Affordable Sustainability

Two houses from (nearly) the same place find the same affordable solutions, but diverge in their expression of sustainability

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: The solar-powered houses that lined the National Mall for the fourth Solar Decathlon made it clear that the sustainable design movement is becoming more self-assured and sophisticated. The student-designed and built houses used a wide variety of materials (stone, wood, steel, plastic composite) and spatial organizations not seen in past decathlons. Moreover, the solar photovoltaic panels used to power the houses and sell energy back to the grid are better integrated into the designs, while the need for them has been effectively minimized by simple, passive sustainability design features.

In its massing and circulation patterns, the Zerow

House references Gulf Coast detached vernacular shotgun houses.

Photo courtesy of Eric Hester.

But within this maturing and diffuse field of design, much about the contemporary state of alternative energy residential building can be learned from some of the most similar projects. The Rice University and University of Louisiana—Lafayette houses are both grounded in the same geographic and climate region, and thus make the same vernacular architecture references. They share similar spatial and programmatic plans, and both make the case that net-zero energy homes can be made affordable for middle- to low-income Americans. The two houses differ in materiality and their willingness to break formally with housing traditions, but within these differences lie important lessons on the barriers to widespread adoption of renewable energy houses nationwide.

Sponsored by the United States Department of Energy and cosponsored by the AIA, the Solar Decathlon pits multidisciplinary teams of college students (from architecture, engineering, interior design programs, and more) against each other in a 10-part competition to design and build a solar-powered house. The entries are judged on architecture, net-metering (the ability to sell solar power back to the grid), engineering, lighting, market viability, and other categories. For three weeks in October, the houses are placed on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and the public is invited to tour the houses and learn about sustainable residential design. This year, 20 teams from four countries competed.

Core sustainability

With a $140,000 price tag, Rice University’s Zerow

House was by far the least expensive in the entire competition

(most cost three to five times as much). The school’s entire

participation in the program cost only $250,000 “and that includes

the pizzas we eat for lunch and our airplane tickets,” says

David Dewane, an architecture student and project leader. The house

will be given to a Houston nonprofit, The Row

House Community Development Corporation, which will donate it to

a low-income family.

A green screen on the front of the Zerow House

creates another solar shade and is covered in native Texas vines.

Photo courtesy of Eric Hester.

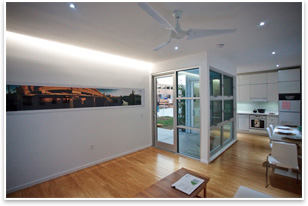

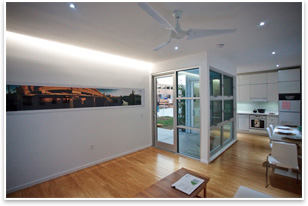

The Zerow House is a minimalist, abstracted interpretation of a Gulf Coast shotgun row house, native to Houston where Rice is located. And, at 520 square feet, it’s one of the smallest entries. However, the perpendicular insertion of a recycled wood and plastic composite porch into the middle of the boxy, rectangular house makes the space seem larger and lighter, as glass walls and doors open to the outside around it, bringing in natural light and blurring the boundary between indoors and outdoors.

The porch, shaded by a cantilevering steel screen, is called the house’s “light core” and is one of its primary organizing elements. “The reason it feels that big is because you’re projecting yourself out into the light core, but I’m not counting that [square footage] because I’m not conditioning it,” Dewane says.

Programmatically, the house is organized like a typical detached Gulf Coast shotgun house, with a narrow profile and a linear progression of spaces that gradually become less and less public. From the side entrance, visitors progress through the living room, dining room, porch and light core, kitchen with adjacent bathroom, and then the bedroom, separated with a sliding door. Though the Zerow House has stripped away many of the vernacular features that make it recognizable as a shotgun row house (like a gabled roof), its traditional circulation and spatial organization patterns are reinforced by a narrow strip of LED lights that run perpendicular to the light core.

The bathroom and kitchen comprise the “wet core” (the other primary organizing component of the house) and contain all water fixtures. Dewane and his team are investigating ways to base pre-fabrication techniques around the wet core to make the Zerow House even more affordable. “In the future, we’ll be able to pre-cast a piece like that you could drop on site, and you could build a very inexpensive house around it,” he says. Structurally, the house uses stick-built framing (another traditional vernacular reference), but it’s clad in corrugated Galvalume siding, a composite of recycled steel and aluminum. The front of the houses features a green screen that provides extra solar shading. Covered in flowering native Texas vines, the simple and succinct house gets extra mileage out of this rich change in texture and color.

Both the Rice and University of Louisiana houses were willing to take advantage of the economies of big-box consumer scale to meet their affordability goals. In fact, this is perhaps a primary way they were able reduce costs. The teams used many off-the-shelf products (bathroom fixtures, shelving, low-energy fans, windows) from retailers such as IKEA, Home Depot, and the Container Store. (The Zerow House even incorporates used furniture.) By using these products, the houses represent a vision of sustainability that is not automatically antagonistic to traditional consumerism and also realizes that custom wood-carved furniture might consume more in dollar amounts than it gives back in reduced carbon footprint. Certainly, big-box consumerism encourages practices that aren’t sustainable, (like shipping products from across the globe that require a car to access and purchase), but Dewane says the tradeoff is worth it. “You’ve gotta be a realist, man,” he says. “If Home Depot is selling a dual-flush toilet and we can get it, I think it’s good to buy that.”

Peter Yost, a residential sustainability expert at Building Green, says big-box stores have been better at stocking eco-friendly products, and that the number of third-party resources that evaluate products and discern true sustainability from “greenwashing” has increased immensely.

The Zerow House’s narrow profile and opening to the light core porch means that breezes travel across the house easily, requiring little artificial ventilation and climate control. (The house uses several small mini-split ductless systems for heating and cooling.) The green screen solar shade, high-efficiency insulation, and LED lighting fixtures make the house a pure passive sustainability machine. Thus, the solar panel array and solar hot water system on the house’s flat roof can be as small and inexpensive as possible. “A lot of what we’re doing is not creating the need [for more power] so we don’t have to generate more power,” says Dewane.

Inside the Zerow House, the “light core” porch pushes into the middle of the house with glass doors and operable windows, creating the perception of more space than the 520-square-foot home actually contains. Photo courtesy of Eric Hester. Yost says that the return on investment for passive energy efficiency features like natural ventilation, optimal solar shading, and a tight building envelope is 10 times greater than active renewable energy generation systems. That’s a lesson that seems to have been internalized by the decathlon teams. They’ve become savvier at lightly and sparingly integrating solar panels into their designs, negating the need for superfluous metallic armatures hefting photovoltaic panels skyward, which cluttered house designs in years past.

Dewane says he never felt that he had to compromise the house’s performance or aesthetics to meet his bottom-line budget goals. The judges of the architecture competition seemed to agree. The Zerow House won second place. In the market viability competition, Rice came in second to the University of Louisiana. In fact, with a more rigorous and modern structural system, Dewane says he could have built the Zerow House for less than $100,000. “There are a lot of teams for [the 2011 competition] coming through right now, and I’m telling them, ‘Do it for $99k. You would be a rock star,’” he says.

But, like the best sustainable buildings, the Zerow House is upfront about the sacrifices required to rebalance human habitation with nature. Dewane’s houses’ performance is predicated entirely on its lightness, efficiency, and small size. “You can’t have a 2,500-square-foot house,” he says. “You have to reduce the space.”

“Something about a gable”

Photovoltaic panels typically

cost $9/watt, with prices continually declining, making projects

like the Rice and University of Louisiana houses more and more practical.

Though the increasing adoption of voluntary rating systems like LEED and Green

Globes has put downward pressure on sustainable products, Yost

says this progress has been mostly incremental and small. There have

been few notable increases in PV panel efficiency, he says, and pre-fabrication

techniques aren’t yet refined enough to coordinate the integration

of sustainable building products and systems into homes at a wide

scale.

Also, consumers often lack the kind of savvy required to motivate the home building industry to change rapidly the way they build. People don’t approach buying a home with the same value proposition as they do for any other durable good, Yost says, despite the fact that a house is likely the largest purchase they’ll ever make. When a consumer buys a car or a computer, they’re concerned about its gas mileage or processor speed. When they buy a house, they’re concerned about square footage. “They would never ask, ‘What’s the price per pound of that car?’” Yost says. “That’s an absurd metric.” With cars and other goods, people look for performance and quality. With houses, they mostly look at quantity of space. People simply aren’t accustomed to thinking of their homes as service-providing devices. “We don’t ask what our houses do for us,” says Yost.

Beau Soleil, a high-tech vernacular blend

Such a lack of performance awareness means a conservative marketplace and slow changes in residential sustainability and aesthetics. The University of Louisiana—Lafayette’s house does more to bridge the gap between traditional tastes for houses and progressive visions of sustainability than the Rice house. Called Beau Soleil, the Louisiana house shares a long and narrow rectangular footprint with the Zerow House inspired by Cajun cottage shotgun houses native to Louisiana. However, Beau Soleil is covered in locally sourced cypress and topped with the quintessential signifier of home and hearth: a gabled roof (this one covered in solar panels). “If you squint at it, you can see a traditional Louisiana home,” says Geoff Gjertson, AIA, the architecture professor who led the University of Louisiana—Lafayette team. “There’s something about a gable that says home for people.”

The rear of the Beau Soleil House. Its gabled

roof is covered in solar panels. Photo courtesy of the University

of Louisiana at Lafayette.

Gjertson’s house is 800 square feet and cost $380,000 to build. Without some of the design details that surround the house (like the porch and landscaping), he says the price could be as low as $250,000 or less. That should be well within the budget of the 50- and 60-something Baby Boomer empty nesters Beau Soleil is targeted at.

The gabled roof (which Gjertson says is a response to the need for high ceilings that let hot and humid Gulf Coast air ventilate out of the house) does acknowledge that low- and middle-income people aren’t typically known for their progressive taste in houses. Overall, the Beau Soleil house is a warmer and more familiar approach to sustainability than the Zerow House, both in terms of form and materials. Inside the Louisiana house, darker, warmer woods like ipe and oak draw a sharp contrast to the white-walled and bamboo-floored art gallery box inside the Rice project: much more of a “machine for living,” according to Le Corbusier’s famous dictum, than the Beau Soleil project.

The Beau Soleil’s designers were more concerned with creating open and inviting social spaces for entertaining friends and family than refining a classic Modernist ideal. The primary design feature they’ve used to accomplish this is a moveable glass wall system that alternately encloses and opens up a “dog trot” porch in the middle of the house. This internal porch can either be left open to the outside, allowing outdoor breezes to flow across the house’s narrow profile, or the walls can shift to close off the porch from the outside, opening it to the adjacent kitchen (on one side) and the living room (on the other). In either scenario, residents of the house will have a flowing continuation of the social spaces that form around the living room and kitchen with visual or direct access to the outdoors. Providing this kind of flexible and expansive social space for family gatherings and meals, Gjertson says, was a vital part of honoring the project’s Southern cultural roots.

The front of the Beau Soleil House. Photo courtesy

of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

The Louisiana house displays the same public-to-private progression of spaces seen in the Zerow House and shares its off-the-rack approach to affordability, using non-custom windows and efficient ductless mini-split HVAC systems. Operable black steel hurricane shutters address another local climate condition. When the competition is finished, Gjerston says, the house will be used as a building performance research lab back at the university.

Sun is still rising

To the throngs of visitors that wandered the

National Mall this month, the Rice house says: “This is all

you need for sustainable housing.” The Louisiana house says: “You

can still recognize sustainable housing.” That these different

conclusions sprung from houses designed for such similar places with

such similar parts is a testament to the wide-open, unexplored realms

of innovation and possibility in the still-coalescing residential

sustainability design world.

|