| Division1

Architects’ Lacey Condo Celebrates DC’s Moment with Communal

Luxury A building that acknowledges the values of public civil servants—with style

Since last fall, when the Washington political establishment began floating storied Wall Street institutions financial lifeline after lifeline, a bit of the prestige of directing the world’s largest economy migrated southward down I-95 from New York. Add this to DC’s rapidly revitalizing (and gentrifying) neighborhoods and the ever-present Obama buzz, and the cultural life of the city may yet be ready to outgrow its New York-induced inferiority complex. All of this means that there probably isn’t a better time for Division1 Architect’s Lacey condominium building. With this shift in power and prestige comes an openness to high-design luxury bordering on hedonism—already established in certain other cities that have unexpectedly found themselves as supplicants to Washington’s public money trough. No longer must workaholic policy wonks trudge home to bland motel-corridored, quasi-retro brick, cookie cutter apartments. Now is the time for hallway atriums, roof decks, and sliding glass bedroom doors!

Wilson’s son Lacey Wilson Jr. sold the restaurant and its parking lot to developer Imar Hutchins several years ago with the intent to build a condominium on it. The pitched-roof, row-house-style restaurant exudes neighborhood familiarity in a changing urban context. Across the street, further up the hill to the north looms Cardozo High School, designed by the St. Louis architect William Ittner in a grand Collegiate Gothic style and completed in 1916. The Lacey mirrors Cardozo’s topography. From the street, a retaining wall demarcates Cardozo’s campus grounds, and the school itself creates another vertical demarcation further north. Likewise, the two-story Florida Avenue Grill has the four-story Lacey hovering above it, creating street valley walls on both sides.

“Us showing respect [for the neighborhood] was to move forward and think forward,” says Ali Honarkar, Assoc. AIA, of Division1 Architects. “We had to come up with a building that had its own personality and stood on its own.” Familiar space

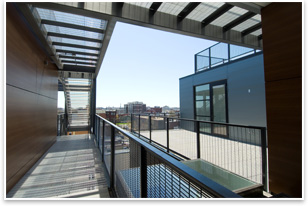

“We wanted to give something back to the community,” he says. “This is an urban building. It doesn’t hide what it is.” Accountability and transparency Though the building is only four stories tall and is on a constricted urban site, Division1 managed to give the vast majority of units a dedicated outdoor space of their own—a patio, balcony, or roof deck. There are two common roof decks accessible to all, and the views to Washington’s monumental core and beyond will be a prime selling point for the building. Finding these kinds of spaces on this site without repetitively stacking balconies wasn’t always intuitive and required a resourceful design eye. When a small square of space below grade that was supposed to be landscaped wasn’t able to accommodate a tree, Honarkar turned it into a patio that’s open to they sky for a cellar-level unit.

It’s a concerted push for community in a changing neighborhood that would probably be unrecognizable (save the Florida Avenue Grill) for anyone around when the restaurant was new. This design-instilled sense of enlivening communal voyeurism takes the building beyond the simple amenity-stacking that doesn’t do anything to get residents to connect. (A gym so residents can jog on a treadmill, silently plugged into a television via headphones. A businesses center so bleary eyed office workers can scan and e-mail documents long into the night.) This implicit focus on community interaction makes The Lacey a more public and civic building, governed by the rules of public transparency (at the Lacey—quite literally—with glass and the ability to see neighbors) and accountability (which comes with neighborly familiarity). That makes it the more appropriate for Washington, D.C., where the cultural dialogue is largely set by civil servants and elected leaders for whom no political crusade can sustain itself without a community of support. |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› D.C. Architect Suman Sorg Neighborhood Modernism Gains a Foothold in the Nation’s Capital

› St. Louis Residential Tower Design Unveiled

› Meltzer/Mandl Architects Take on the Brooklyn Brownstone, Now in Glass and Metal

› Condo Sell: A Modern Bachelor Pad for Swinging Singles

See what the Housing

and Custom Residential Knowledge Community is up

to.

Do you know the Architect’s Knowledge Resource?

The AIA’s resource knowledge base can connect you to “Risk

Management For Architects in the Design of Multifamily Community Associations.”

See what else the Architects Knowledge Resource has to offer for your practice.

How do you .

. .

How do you .

. . Taking things forward

Taking things forward Clearly, the Lacey does not mirror the neighborhood’s formal

design language. Its unabashedly Modern steel and concrete create

a sharp contrast with the buildings that surround it, and this definitive

statement is what makes it work.

Clearly, the Lacey does not mirror the neighborhood’s formal

design language. Its unabashedly Modern steel and concrete create

a sharp contrast with the buildings that surround it, and this definitive

statement is what makes it work.

For a building that pitches its serious design pedigree as a luxury

feature, (its budget was actually a rather modest $7 million, which

probably puts it in a different class than

For a building that pitches its serious design pedigree as a luxury

feature, (its budget was actually a rather modest $7 million, which

probably puts it in a different class than