| D.C. Architect Suman Sorg’s Neighborhood Modernism Gains a Foothold in the Nation’s Capital Will yuppies reshape Washington’s conservative architecture environs?

Summary: Sorg and Associates’ Visio and Murano projects in a gentrified neighborhood are contemporary Modernist condos that draw their forms from neighborhood mainstays (row houses and a neighborhood church) and also knit these structures together with a transitional and proportional decrease in scale. These condos and several others are creating a pocket of contemporary residential architecture in and around an area that has become a mecca for young professionals seeking out its cultural and nightlife attractions.

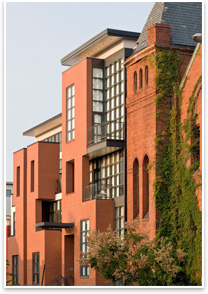

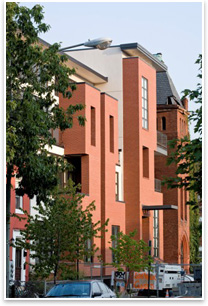

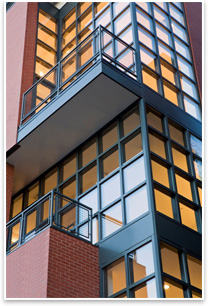

Despite their Modern, flat-roofed design, both the Visio and the Murano buildings (they are attached to each other) take their cues from traditional neighborhood forms—in this case, the typical Washington row house, and a red brick historic church on the south side of the development. Sorg says they paid “a great deal of attention” to the now-derelict church, which has recently been granted historic preservation status. The front façades of both buildings are balanced with two opposing elements: sculptural, protruding brick blocks, which Sorg says reference rowhouse bay windows, and recessed window spans that wrap around the buildings corners.

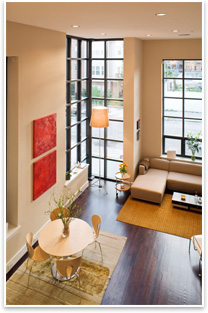

The Visio and Murano offer an example of Sorg’s established warm and humanistic approach to Modernism, which also is likely a savvy business decision in the Washington architectural market, where most of her business is. For contemporary architecture neophytes, pure Miesian glass box architecture would likely be a stretch too far. “There has to be more than one experience in a space,” Sorg says, evidenced by her balance of glass and brick, as well as the well-proportioned interior views of the Visio and Murano.

Like nearly everywhere else, purely private investment is using architecture as a branding mechanism to sell a lifestyle—and is also making some of the boldest architectural statements in the city. Aided in part by Washington’s rise as a destination city for young professionals, Shaw and its adjacent neighborhoods are changing rapidly, and its property values have been spiking. They jumped 33 percent from 2004 to 2006 alone, according to the Washington Post. This change has helped create a tentative incubator for contemporary Modern architecture. As young (and often white) professionals move into formerly African-American neighborhoods, Sorg says that the new demographics require a very different living program that is better served by sparsely programmed, high-concept condominiums. The average 20- or 30-something freelance graphic designer-type that these buildings are marketed to have much less need for the traditional living space that typically come with a Mid-Atlantic row house.

|

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› St. Louis Residential Tower Design Unveiled

› Sweet Homes, D.C.: 2006 Washingtonian Residential Design Award Winners

› National Building Museum to Present Inaugural Atherton Lecture and “Framing a Capital City” Symposium

Visit Sorg and Associates Web site.

See what the AIA Housing and Custom Residential Knowledge Community is up to.