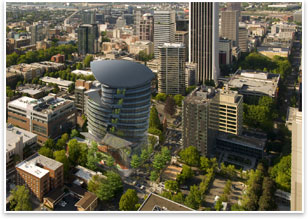

| Biophilic Oregon Sustainability Center Will Be a Locally Grown Original Oregon coming together to meet the Living Building Challenge

The Oregon Sustainability Center’s largest photovoltaic array is on its roof, oriented southwards toward the most direct sunlight. How do you . . . design a building for a diverse group of clients that meets the Living Building Challenge with two varying design languages? Summary: It’s hard to find a more emblematic project for the contemporary sustainability movement than the Oregon Sustainability Center. Now in the final stages of a feasibility study, this highly sustainable high rise in Portland, Ore., combines the efforts of the nonprofit, education, business, and public sectors to create a building that adheres to the most stringent sustainability certification standard that exists, and uses several distinct design languages and systems to get there. It takes the sustainability conversation out of the design lab and into classrooms, civil servant offices, business board rooms, and nonprofit outreach centers. The center will serve many functions: offices for nonprofits and businesses, university classrooms, a place for building performance research. Its designers and tenants hope it will emerge as a literal icon of sustainable urbanism for one of the nation’s most progressively green states and cities. Collaborating for the challenge “The design itself is a vehicle to analyze the feasibility of the Living Building Challenge,” says Kyle Andersen, AIA, of GBD. Its formal qualities (as detailed by a feasibility study released mid-June 2009) could change direction, but the project’s designers and clients say their analysis so far has given them the confidence they need to move forward with designing what would become a record-breaking building of unparalleled efficiency.

Sky and roof gardens offer visual interest back to the surrounding city. The Living Building Challenge, developed by the Cascadia Green Building Council in 2006, forgoes a lengthy credit system (like Green Globes or LEED) for a few simple prerequisites. Any building that wins the Living Building title must perform at net-zero energy, water, and waste. Essentially, the challenge requires buildings to be nearly as environmentally unobtrusive as a tree. No one has yet succeeded in meeting the Living Building Challenge. Further complicating GBD and SERA’s task (they are equal co-designers on the project) is the fact that the center is the diametric opposite of the building types that typically reach for the Living Building Challenge. Most projects that aspire to this level of sustainability are small, rural nature interpretive centers made of locally harvested wood—a structure that intuitively occupies the land with a light touch. The Oregon Sustainability Center, however, is a 225,000-square-foot, 13-story high rise of glass and concrete on a tight urban site in downtown Portland. It’s the largest project in terms of square footage and verticality to ever attempt the Living Building Challenge. To make it easier for the building to meet these goals, the project’s clients agreed to shrink the size of their own building and compromise on programming. That’s just one illustration of the commitment GBD and SERA have seen from them. Regular occupants will have to accept less energy-intensive climate controls, which means warmer temperatures in the summer, cooler ones in the winter, and only one sink with hot water in bathrooms, says Andrea Durbin, the founding board member of the Oregon Living Building Initiative—a consortium of about a dozen Portland sustainability nonprofits that will occupy the building. In October, the Oregon legislature will vote on an $80 million bond for building the sustainability center. Organizers are also going after federal economic stimulus money, and individual nonprofits are searching for grants as well. The total cost is not yet formalized, but the building’s designers hope that construction can begin in the summer of 2010. In addition to housing nonprofit offices, the building will also contain classroom and office spaces for the seven schools in the Oregon University System and the four universities in the Oregon Built Environment and Sustainable Technologies Center (BEST). The building itself will be one large, continuously running experiment, as researchers will investigate the performance, life-cycle costs, and use patterns of this singularly sustainable building. Perhaps the most significant aspect of what goes on at the Center will be the relationships built between various tenants. “How do we bring the different interests together?” asks Durbin. “The intention is to try to co-locate and build on these synergies in terms of a sustainability agenda.” If all these diverse groups find a place in the building, organizers see it as a one-stop sustainability shop. Someone might stop by to take a class on photovoltaic panels or rainwater recycling systems. They could then visit a city office to apply for tax credits for installing them. They could even meet with contractors that can install such equipment. The building’s project team (the vast majority of whom are based in Oregon, including developer Gerding Edlen have similarly been working collaboratively. GBD designers have been sharing their offices with SERA, as well as various engineers and consultants. A programming charrette in February and a design charrette in April brought all stakeholders together to map out directions for the project. The April charrette was five days long, and 50 to 100 people were in attendance at any one time. “Only through a process like that are you going to get the kind of creative brainstorming and innovative ideas that will help overcome a lot of the challenges to doing a project like this,” says David Kenney, executive director of Oregon BEST. Clark Brockman, AIA, of SERA, says the intense collaboration of the charrette meant he got to watch as wide swaths of the project’s conceptual organization came together in about an hour on a white board. This rapid pace has continued. The Center’s architects have only had eight weeks to complete the final feasibility study design. “It’s one of the truest examples of integrated design I’ve ever seen,” he says.

The landscaping and thin, tall wood columns create a forest-like atmosphere under the pedestrian plaza. Reaching for the sun As a purely vertical solution to the problem of energy efficiency and generation, each floor of the building rotates four degrees on axis towards the ideal solar orientation. This kind of metered, mathematical change over distance calls to mind natural designs, like a nautilus shell that spirals outward at regular intervals. Andersen also has another simple biophilic metaphor to describe it: “A lot of the things you see the building doing in form are basically the form of the building adjusting to where it wants to be in nature. If a flower or tree came out of the ground it would instantly start to torque and turn itself toward the sun.” All of the building’s energy is generated by solar power. The building’s largest photovoltaic array is shaped like a tear drop and sits, cantilevering, on the roof, angled upward like a leaf drifting to the earth from a tree. Its broad edge is pointed nearly due south, as that’s where the most consistent light comes from in Portland. There are also south-side photovoltaic arrays on the 10th-level roof canopy, which covers a sky garden. This garden sits on top of an arcing crescent-shaped section that projects out from the side of the building. Horizontal louvers on the south side of the building serve three purposes, acting as photovoltaic panels, sun shades, and light shelves bouncing light back into the building as needed. “That south side is a powerhouse of energy production,” Andersen says. The building’s curtain wall also has integrated photovoltaic panels.

The center keeps to an approachable and intimate scale. Further below, two roof canopies of translucent solar panels at the third and fourth levels cover a pedestrian plaza, allowing light to filter down to the ground. “It will dapple the floor of the plaza, like a forest floor,” says Andersen. Reinforcing this pastoral impression will be the wood structure and columns that stand like tree trunks, supporting the roof canopy. Visitors to the Oregon Sustainability Center will get a rich sensory experience as they pass through a forest of thin wood columns and elevated walkways with views into the building. A light rail train moves across the site. The wood (it’s unclear exactly what kind they’ll use) is also a nod to Oregon’s traditional lumber industry. “We wanted to soften and warm the palette and bring nature into it,” Andersen says. With this material choice, the sustainability center embraces two distinct sustainable design traditions that often are seen as opposed—steel, concrete, and glass—blending a high-tech sheen from the building’s curtain wall and general profile and the warm and woodsy log cabin feel of its plaza. Both design languages have a place in the contemporary sustainability movement—the high-tech approach for its effusive optimism in the ability of science to create new ways to work within limitations, and the log cabin method for its modesty and deference to the earth—but it’s rare that a building embrace both paths so directly. The building will not use any traditional HVAC air cooling systems, aided in part by the Pacific Northwest’s mild climate. It will instead rely on radiant slab systems and geothermal wells for heating and cooling. The center will collect all its water from rain, which is treated for potable use in a basement collection tank. Wastewater is cleaned and recycled on site with bioreactor digester tanks and is then filtered by “Living Machine” systems that works like natural wetlands and estuaries to clean the water. These systems (which bring wastewater up to non-potable levels) will make up a 1,600-square-foot garden area in the fourth floor. In the users’ hands |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Oregon Center Relies on Big-Time Collaboration for Big-Time Sustainability

› The Design Alliance’s Center for Sustainable Landscapes Finds Ultimate Sustainability in the Balance

› From Farm to Market, Down the Stairs, Around the Block

› Biophilic Design Connects Humans with Nature

› Nature Finds a Way: The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

› See what the Committee on the Environment Knowledge Community is up to.

Do you know the Architect’s Knowledge Resource?

The AIA’s resource knowledge base can connect you to a Best Practices primer on the Living Building Challenge by Lance Fletcher, AIA.

See what else the Architects Knowledge Resource has to offer for your practice.

See what the AIA Committee on the Environment is up to.

Images Courtesy of GBD and SERA.