| Randall Stout’s Art Gallery of Alberta Loops Together the Arts, Nature, and Time Itself Contemporary forms reaffirm the creative vitality of all design languages

Summary: With the circular ribbon of steel that runs through Edmonton’s Art Gallery of Alberta (AGA) in Canada, Randall Stout, FAIA, has arrived at a powerful symbol of the eternal vitality and continuum of creation of the arts, culture, and the natural world. The museum preserves much of the urbanistically aloof, original concrete facility while adding new galleries and a large glass atrium across which a curving, continuous ribbon of stainless steel moves thought the interior and exterior like a piece of string threaded through the surface tension of a soap bubble, gradually morphing from structure to sculpture and back again. The steel ribbon is looped, with no beginning and no end, though its circuitousness is occasionally lost in its folded, abstracted sculptural presentation. See what the Committee on Design Knowledge Community is doing.

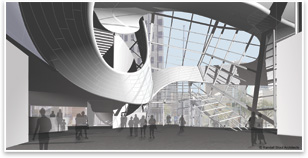

Images courtesy of Randall Stout Architects. 1: The Art Gallery of Alberta during the day. “If you think of it being unfurled,” says Stout, principal of his eponymous Los Angeles-based firm, “it’s a single piece of cloth.” It’s a reminder that despite changes in taste, form, and medium, all artistic expressions are due for circular revision one day, and that the last generation’s flop can always hope to be the next generation’s discovered treasure. That’s an especially important lesson for a museum that will dedicate 80 percent of their exhibition space to changing exhibits and traveling shows. And although phases of art and culture may be mutable but repetitive, the iconic regional and natural forms that influenced the ribbon’s expression and the building’s form deserve an idealized permanence, also hinted at with the looped ribbon. Stout has several such comparisons for the serpentine curves of the ribbon and the loosely assembled play of transparency and opacity that make up the rest of the AGA’s addition (the twists and turns of the Saskatchewan River that runs through the city, Inuit stone sculptures, the northern lights), but these were merely implicit ways for him to understand the forms that were emerging in the design process. “It’s not a storyline that people have to be told or understand,” he says. But these forms are undeniably there, and Stout even refers to the ribbon as the “borealis.” So, this gesture has brought together both astronomical phenomena that existed for ages without man’s appreciation or existence, and the quarrelsome, humanistic jockeying of art salons, largely played out over the time-scale of the contemporary news cycle. This dichotomy is matched by the presence of rational, functional spaces within free-form glass expressionism, and the re-investment into existing infrastructure with contemporary Deconstructivist form. An invitation in from the cold Stout’s design reuses 37,000 square feet of the original 55,000-square-foot structure, designed by the local architect Don Bittorf. Bittorf’s 1968 Brutalist composition (then known as the Edmonton Art Gallery) suffered from poor insulation and vapor barrier protection, and its concrete had began spalling down to its reinforcing steel. The competition brief for the new AGA called for the architects to preserve as much as they could of the original building by stripping it down to its bare structural elements and building it back up again. It also called for architecture firms to find ways to get the building to be a more interactive and visual presence in downtown Edmonton. Eight galleries across three levels in the original build are being renovated, and its roof will contain a sculpture garden. Stout approached the building’s lack of engagement with the urban fabric around it by basing his $65 million, 27,000-square-foot addition around a four-level, full-length glass atrium. This atrium primarily contains public and circulation spaces, but his design also adds large gallery spaces as well. On the west façade of the building, a rectilinear zinc-clad volume containing galleries cantilevers enigmatically over the glass atrium wall. It is supported by a two-story steel truss on the perimeter with diagonals in plane with the wall. These verticals truss components become columns and thread down through the existing structure to new foundations.

Suspended circulation Between the steel supports, aluminum mullions form rectilinear grids across the atrium curtain wall. A free-standing, cantilevered stair that tapers in width as it rises takes visitors to the upper level galleries. Throughout the interior and exterior of Stout’s museum, his steel ribbon makes organic, evolving transitions from one structural function to another. It begins at the front entrance as a roof canopy and then it drops down nearly to the ground level, curling around itself to form what Stout and his team call the “snow cone.” This cone will collect snow and ice from the building’s roof, and, given Edmonton’s long and intense winters, looking through the transparent atrium wall into this structure could be compared to staring into the heart of an ancient glacier; another way his design references the perpetual cycles of the natural world. The ribbon then rises up the west side of the museum and acts as a sunscreen. It stretches out to become a gallery roof and then cradles back into the building to encase an elevated members’ lounge. From this free-form atrium (clearly influenced by Stout’s former boss Frank Gehry, FAIA) the AGA’s white-box gallery spaces are calm, rectilinear, and functional. Visitors are eased out of the ebulliently expressive atrium into the largely rational galleries by scaled-down ceiling heights that create “gallery foyers,” interspatial zones that prepare patrons for a quieter visual experience.

Revision |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

How do you . . .

How do you . . .

To deal with the cold climate and seasonally variable long periods of sunlight and darkness of this extreme northern city, the museum is intensely insulated, and its glass sections will feature high-efficiency glazing. It uses a wall system that places an insulating air cavity between exterior and interior walls (a common system in Canada that’s relatively untested in the United States), in addition to other sustainability and energy efficiency features.

To deal with the cold climate and seasonally variable long periods of sunlight and darkness of this extreme northern city, the museum is intensely insulated, and its glass sections will feature high-efficiency glazing. It uses a wall system that places an insulating air cavity between exterior and interior walls (a common system in Canada that’s relatively untested in the United States), in addition to other sustainability and energy efficiency features.