Zaha Hadid’s Quicksilver Forms Fuse Together Another Guggenheim Hermitage Museum

As they leave Las Vegas, the two art giants look on to Lithuania

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: The Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in Vilnius, Lithuania, unites formally and functionally disparate gallery types within a richly multifaceted whole. Although it’s a singularly iconic presence that seems formally divorced from its immediate context, it is designed to be porous and communicative with the surrounding urban fabric. Summary: The Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in Vilnius, Lithuania, unites formally and functionally disparate gallery types within a richly multifaceted whole. Although it’s a singularly iconic presence that seems formally divorced from its immediate context, it is designed to be porous and communicative with the surrounding urban fabric.

How do you ... design a museum that will house galleries featuring art of many different media types?

In the wake of the closing of Rem Koolhaas’s Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in Las Vegas in May, these two storied art institutions are collaborating again on another project in Vilnius, Lithuania, which will combine the Russian Hermitage’s age-old collections with the Guggenheim’s unparalleled stock of Modern and contemporary art. In the wake of the closing of Rem Koolhaas’s Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in Las Vegas in May, these two storied art institutions are collaborating again on another project in Vilnius, Lithuania, which will combine the Russian Hermitage’s age-old collections with the Guggenheim’s unparalleled stock of Modern and contemporary art.

And unlike the Las Vegas Guggenheim Hermitage, the Vilnius museum, say sponsors, is not based on corporate patronage and commerce. “Here in Vilnius, we have a somewhat different way of thinking,” says Arturas Zuokas, a recent former mayor of Vilnius and a prime instigator of the museum project. “The current aspirations of Lithuania have set a priority that culture is of utmost importance.”

There is an enviable amount of conceptual symbolism to be mined by any artist or designer in this project. (For example—the premier arbiters of high-class culture in nations historically opposed during the Cold War joining together to build in a former Eastern Bloc nation.) But Zaha Hadid’s design isn’t particularly engaged with historical narratives or politics. True to her design pedigree, it’s a formally driven plan, with virtuosic, digitally derived turns of abstract, curvilinear mass and volume.

Complexity through unity Complexity through unity

Hadid’s design was selected after 14 hours of jury deliberation. The design is still in the midst of a feasibility study, commissioned by the Jonas Mekas Visual Arts Center (a collection dedicated to avant-garde Lithuanian art) and executed by the Guggenheim and the Hermitage. Hadid’s firm is examining the project’s potential budget, materials, and technical details. The museum is expected to open in three to five years.

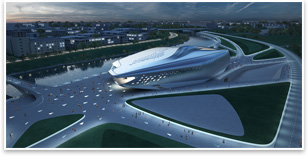

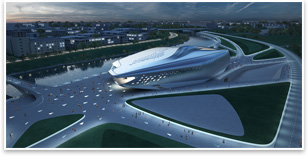

The 140,000-square-foot, four-level museum sits on the banks of the Neris River, which divides Vilnius’s old city center from newer developments to the north. “Our scheme bridges these two parts,” says Thomas Vietzke, the museum's project architect in Hadid’s London-based firm. “It’s a connection device.”

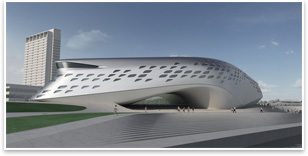

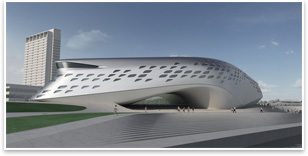

A terraced, landscaped plaza leads visitors to the river, which is to the south of the museum, and up to the building. Patrons enter via the southeast end of the building, through a glass wall permeable to the surrounding urban fabric and under a 66-foot-long curving cantilever. Vaguely teardrop-shaped and perforated with triangular skylights, the museum will be clad in aluminum with a variety of glossy and matte finishes, which will create a rich spectrum of reflections. The bottom sections of the museum are made of concrete, which fuses with the concrete plaza.

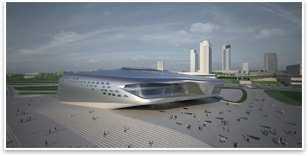

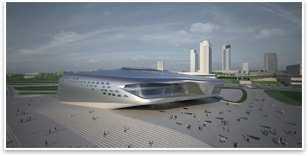

Renderings reveal the building’s most dynamic and expressive feature to be the multitude of ways it expresses its mass from elevation to elevation. At times, it is broad and wide, other times it seems serpentine and narrow. These various façades melt together and resist attempts to define themselves explicitly against each other. Like many of Hadid’s buildings, its form seems to undermine fundamentally the very idea of rectilinear construction that can be subdivided into individual rectilinear components. It’s a unified, sculptural whole, with no elevations denigrated below any other with utility loading docks or mechanical equipment. (A utility entrance is slid underground on the building’s northwest side, and visitors can walk across it on a pathway.) Vietzke says the museum’s computer-driven geometries are a continuation of Hadid’s office’s research into transitioning building design into digital fabrication. Renderings reveal the building’s most dynamic and expressive feature to be the multitude of ways it expresses its mass from elevation to elevation. At times, it is broad and wide, other times it seems serpentine and narrow. These various façades melt together and resist attempts to define themselves explicitly against each other. Like many of Hadid’s buildings, its form seems to undermine fundamentally the very idea of rectilinear construction that can be subdivided into individual rectilinear components. It’s a unified, sculptural whole, with no elevations denigrated below any other with utility loading docks or mechanical equipment. (A utility entrance is slid underground on the building’s northwest side, and visitors can walk across it on a pathway.) Vietzke says the museum’s computer-driven geometries are a continuation of Hadid’s office’s research into transitioning building design into digital fabrication.

Such sculptural complexity is meant to confound the logic of the first glance. Inside and outside, Vietzke says, it invites exploration and intellectual curiosity in order to decode its organization of spaces.

Made by medium Made by medium

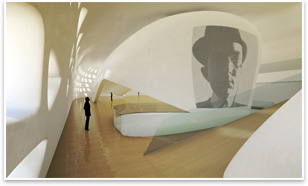

Once inside the museum, visitors find themselves in its central circulation device, a large lobby space Vietzke likens to a canyon. Opening into glass walls on three of the museum’s elevations, the “canyon” is a centrally located void. This division creates three large, solid “feet” that connect the museum to the ground. From the ground floor to the top level, this void is surrounded by galleries adjacent to double-walled “buffer zones,” as Vietzke calls them. These areas offer views and subsequent visual contact down to the first level and also shield the galleries from the noise and daylight of the more public circulation areas. This is also where staircases and circulation platforms are located.

The museum’s galleries are diversely programmed, and their integration into one mass becomes the museum’s primary aesthetic identity. “We started by grouping the many different galleries with different properties and different shapes around a central communication space, which is the canyon, and then [we covered it in a skin],” Vietzke says. “The skin completes the shape and it becomes whole, but still one can sense that it’s composed of single entities.”

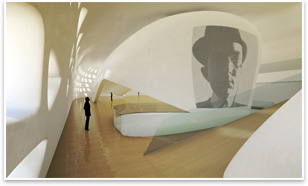

Each of these entities draws its form from the medium intended for it. The multimedia core galleries use freestanding walls as shields against sunlight entering through the building’s skin perforations and skylights to create a more black-box-like level of lighting control, appropriate for video installations and projection art. This device creates a similarly mediated “buffer zone” between more public areas and galleries, like the circulation corridors rising from the canyon lobby. As part of the museum’s non-linear and non-prescriptive circulation patterns, it also creates the required level of lighting discretion without sealing patrons off from the rest of the museum with an explicitly articulated entrance and exit. Designed for the exhibition of Fluxus projects (an artistic movement developed by Lithuanians George Maciunas and Jonas Mekas that established itself in the New York avant-garde art scene of the 1960s and 70s), its multimedia, anti-commercialist DIY aesthetic should suit the museum’s capriciously curving and slanted walls, seen in much of Hadid’s Deconstructivist canon.

Courteously engaging Courteously engaging

Large sculptures are accommodated in the ground floor special exhibit gallery by double and triple height ceilings.

More formally restrained classic galleries that will feature pre-Modern and early Modern works bring in natural, north light from windows and skylights, meant to enhance the viewing traditional painting.

Exhibits featuring Lithuanian culture and history will be housed in a gallery that sits at the edge of the museum in its southeast corner cantilever, which offers views through floor-to-ceiling glass into the old historic center of Vilnius, Lithuania’s capital. Inside, patrons may be looking at representations of some of the same civic icons they see through this window, forming a two-way street of exhibition and voyeurism.

Appropriately enough, the form and material composition of this cantilevered section calls to mind binocular and telescopic imagery. The dialogue between icons of Lithuanian culture and history as they exist as models, text, and pictures and as they exist as urban objects and ideas beyond the museum’s walls are the fulfillment of Vietzke’s promise of a porous urban object. Singular, sculptural, perhaps even other-worldly, but still courteously engaging. |

Summary:

Summary: