| Libeskind’s Second American Project Is a Sculpture that Sways, not a Shrine that Shocks The Ascent transforms itself and the Ohio Riverfront How do you . . . adapt design composition and conceptual motivations to a new building type? Summary: The Ascent adopts a unified, sculptural language of broad symbols that has been previously undeveloped in Daniel Libeskind’s work. It dramatically modulates its form from a horizontal experience to a vertical experience. This residential condo project continues the Cincinnati metropolitan region’s investment in high-profile contemporary architecture with a high-rise that will definitively mark the city’s skyline.

The projects on display here (and elsewhere in Libeskind’s oeuvre) are defined by chaotic fusion and the welding of disparate forms through volumetric virtuosity. Shard-like, angular masses merge and separate with each other and with older, historic structures. Their sense of raw formation is palpable, and it seems odd that these structures could ever grow old and worn, so potent are their riotous forms. The Ascent suggests an entirely different compositional model. It’s a sculptural, singular entity. Instead of creating drama from the juxtaposition of disparate elements, it’s animated by the flowing transformation of curvilinear elements from a horizontal experience into a vertical experience. If the building has a precedent in Libeskind’s work, it’s in his original design for the Freedom Tower at Ground Zero. But that tower hasn’t been built, and won’t be according to Libeskind’s original plan. The Ascent already stands tall.

A new tact? At the Ascent’s opening ceremony in March, Libeskind brought up “market conditions” more times than you might expect from your average creative “iconoclast,” and it’s difficult not to connect this to his experiences with Ground Zero and his new role as a budget line on a commercial developer’s balance sheet. “I learned a lot,” he said of his experience with the Ascent. For example: “How do you create a building in a tough economic frame that is competitive in the market place?”

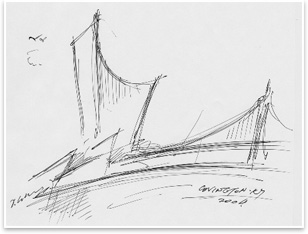

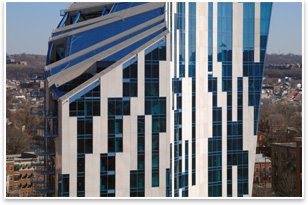

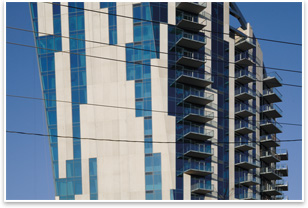

Shape shifting From the tower’s shortest western elevation to its taller eastern face, the 310,000-square-foot building stretches its southeastern corner skyward, curving it inward and cantilevering slightly, around the southern elevation’s ground level entrance and pool plaza. The building contains two elevator cores, both for the privacy of the residents and as a practical design consideration for a building that is 14 stories at the west end and 22 stories at the east end. Most of the Ascent’s structural system is hidden behind its curtain wall, but truss-shaped flying beams at the top of the tower on the north and northeast sides are exposed, drawing on the inherited structural language of Roebling’s Bridge.

From the Ascent’s western elevation, it appears squat and dense, shorter than its 14 stories. It’s a decidedly horizontal experience, more concerned with establishing a strong footprint on the earth than in reaching for the stars. Move a few steps to the east along the southern façade to where the tower peaks at 22 stories in a soft cantilever, and suddenly the Ascent is a shape-shifter. It leaves the earth behind and embodies its name with a lithe, airy, and decidedly vertical grasp for the sky. At this corner, the long, vertical glass and concrete pattern works to compress this edge, pushing it higher into the clouds; something like the maxim that vertical lines will slim down any shopper in a department store mirror. Libeskind must have paid extraordinary attention to how each elevation modulated into the other for this change to happen so seamlessly. The Ascent manages to express this dynamic motion without the sense of collision and confrontation that colors much of Libeskind’s work, and much of the Deconstructivist movement he’s often grouped with. In Denver, where his first American project was an addition to the Denver Art Museum and a complex of attached residences, Libeskind’s museum resembles nothing so much as shards of the Rocky Mountains tumbling together, fused but still angular in the extreme. His Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco (which will open in June) melds two dark, slanted rectilinear masses into a brick and terra cotta early 20th century power station. The Ascent, however, is a unified whole, more suggestive of a single brush stroke than a kit of parts.

The views provided by the Ascent don’t favor either side of the Ohio River. The largest units offer views that wrap nearly 360 degrees around, from the Cincinnati skyline to the hills of northern Kentucky. (Corporex’s two towers do block views to the northwest. This is the site’s biggest disappointment.) These two views, the vertical cluster of Cincinnati skyscrapers and the horizontal expanse of house-lined Kentucky hills, offer vastly different experiences, and their unification in the Ascent is an egalitarian consideration that respects both cities’ role in the Cincinnati metropolitan area. By bringing these two fundamentally different views together, the Ascent again balances vertical and horizontal tensions. What are separate and diametrically opposed views outside of the building become hybridized by the gradual transition from horizontal condo block to vertically dexterous design statement within the building.

“I didn’t change,” he said from behind his trademark black eyeglasses, suit, pants, and boots. “I applied the same notion—that it’s a cultural edifice. It has to resonate with the history of the place. It has to be symbolic in its own way, and it is. We judge cities not just by their civic buildings. We judge them by: How do people live in those cities? What is the quality of their urban fabric?”

At its opening ceremony, right before Covington Mayor Butch Callery told his town’s rebirth story by calling Covington an “exciting and safe” city, he announced that a time capsule will be buried for 100 years that will contain pictures of the Ascent’s construction, news stories, and letters from current owners and then declared March 26, 2008, to be “Daniel Libeskind Day.” A rhyming comic book poster that praised Libeskind for his “elegant structure/The grand Ascent/Given to us by this noble gent/Some call him Clark/And others Kent/This Superman of Polish Descent” made it into the package. “Cincinnatians aren’t doing this so much for the rest of the world as they’re doing it for themselves,” says Sue Ann Painter, executive director of the Cincinnati Architectural Foundation, about her city’s investment in contemporary architecture. Perhaps so, but Libeskind’s Ascent is destined to become the banner symbol to the world outside of Cincinnati of the area’s commitment to the architecture of now. Its 300 feet, visible from the city’s network of bridges that span the Ohio River and from downtown Cincinnati, informs the skyline in ways that Hadid’s museum or the University of Cincinnati’s buildings never will, and that makes its opening not an example of provincial boosterism, but the sharing of a remarkable secret. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Libeskind’s New Jewish Museum Breaks Ground in San Francisco

› Libeskind Plan Selected for WTC Site

› St. Louis Residential Tower Design Unveiled

› Residences that Offer Maximum Pleasure, Minimum Bother

Visit Studio Daniel Libeskind’s Web site.

Read New York Magazine’s “The Liberation of Daniel Libeskind”

Read Paul Goldberger’s, Hon. AIA, account of Libeskind’s WTC project from the New Yorker.